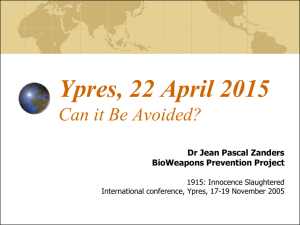

Challenges to Disarmament Regimes: the Case of the

advertisement