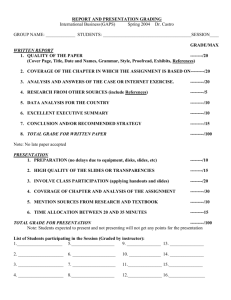

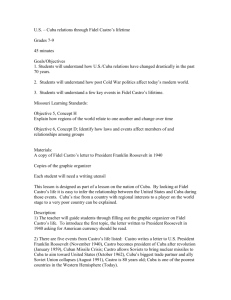

Fidel Castro

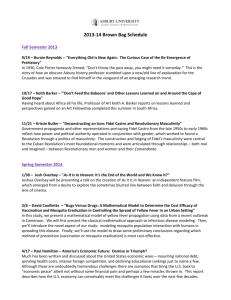

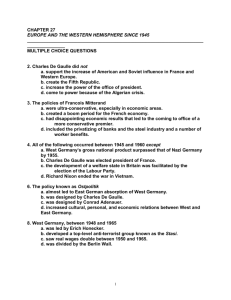

advertisement