No. 104983 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF ILLINOIS Connie

advertisement

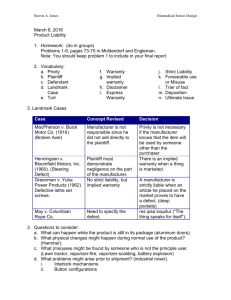

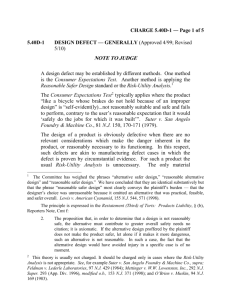

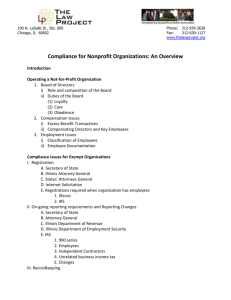

No. 104983 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF ILLINOIS Connie Mikolajczyk, Individually and as Special Administrator Of The Estate Of James Mikolajczyk, Deceased, Plaintiffs-Appellees, vs. Ford Motor Company; Mazda Motor Corporation, Defendants-Appellants, and William D. Timberlake, Defendant. ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) Appeal From the Appellate Court Illinois, First District, No.: 1-05-3133 The Honorable James P. Flannery Presiding BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE PRODUCT LIABILITY ADVISORY COUNCIL, INC. IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS FORD MOTOR COMPANY AND MAZDA MOTOR CORPORATION Stephanie A. Scharf Mary Ann Becker Schoeman Updike Kaufman & Scharf 333 W. Wacker Drive Suite 300 Chicago, IL 60606 (312) 726-6000 Attorneys for Amicus Products Liability Advisory Council POINTS AND AUTHORITIES ARGUMENT......................................................................................................................5 I. The Court Should Hold That the Risk-Utility Test Is the Only Proper Liability Instruction in Cases of Alleged Design Defect in a Complex Product ...................................................................................................5 Restatement (Third) of Torts: Products Liability, § 2 (1998).................................5 A. The Restatement (Third) Advances the Risk-Utility Test for Deciding a Design Defect in a Complex Product.................................................................5 Restatement (Third) of Torts: Products Liability, § 2 (1998).....................5, 6, 7, 8 Restatement (Second) of Torts § 402A (1968) ....................................................5, 6 Suvada v. White Motor Co., 32 Ill. 2d 612 (1965)...............................................5, 6 B. Sound Policy Reasons Underlie Use of the Risk-Utility Test for Complex Products ..................................................................................................................8 Restatement (Third) of Torts: Products Liability, § 2 (1998)...........8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Prosser and Keeton, Law of Torts 699 (5th ed. 1984) ............................................10 Davis, Design Defect Liability: In Search of a Standard of Responsibility, 39 Wayne L. Rev. 1217, 1236-37 (1993) ...................................................................11 C. The Majority of Jurisdictions Across the Country Have Adopted the Risk-Utility Test to Determine Design Defect for Complex Products.............12 Townsend v. General Motors Corp., 642 So. 2d 411, 418 (Ala. 1994) .................12 Dart v. Weibe Mfg., 709 P.2d 876, 878 (Ariz. 1985).............................................12 Soule v. General Motors Corp., 882 P.2d 298, 310 (Cal. 1994)............................12 Barker v. Lull Engineering Co., 573 P. 2d 443, 452 (Cal. 1978) ........................ 12 Comacho v. Hondo Motor Co., 741 P.2d 1240, 1247-48 (Colo. 1987).................12 Mazda Motor Corp. v. Lindahl, 706 A.2d 526, 532 (Del. 1998)...........................12 Warner Fruehauf Trailer Co. v. Boston, 654 A.2d 1272, 1276 (D.C. 1995) ........12 Radiation Tech., Inc. v. Ware Constr. Co., 445 So. 2d 329, 331 (Fla. 1983)........13 i Banks v. Ici Ams., 264 Ga. 732, 735 (Ga. 1994)....................................................13 Miller v. Todd, 551 N.E.2d 1139, 1141-42 (Ind. 1990).........................................13 Wright v. Brooke Group, Ltd., 652 N.W.2d 159, 169 (Iowa 2002) .......................13 Nichols Union Underwear Co., 602 S.W.2d 429, 433 (Ky. 1980)........................13 Johnson v. Black & Decker U.S., Inc., 701 So. 2d 1360, 1363 (La. App. 1997),..13 La. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 9:2800.56 (2007) .................................................................13 Guiggey v. Bombardier, 615 A.2d 1169, 1172 (Me. 1992) ...................................13 Nissan Motor Co. v. Nave, 129 Md. App. 90, 118 (Md. App. 1999) ....................13 Uloth v. City Tank Corp., 384 N.E.2d 1188, 1193 (Mass. 1978) ..........................13 Prentis v. Yale Mfg. Co., 421 Mich. 670, 691 (Mich. 1984) ...........................13, 14 Forster v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., 437 N.W.2d 655, 661 (Minn. 1989) ........14 Miss. Code Ann § 11-1-63(f) (2003) .....................................................................14 Williams v. Bennett, 921 So. 2d 1269, 1276 (Miss. 2006).....................................14 Rix v. General Motors, 723 P.2d 195, 202 (Mont. 1986) ......................................14 Thibault v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., 395 A.2d 843, 846 (N.H. 1978) .....................14 N. J. Rev. Stat. § 2A:58c-3a (2007).......................................................................14 Diluzio-Gulino v. Daimler Chrysler Corp., 897 A.2d 438, 441 (N.J. Super App. Div. 2006) ..............................................................................................................14 Smith v. Bryco Arms, 33 P.3d 638, 644 (N.M. App. 2001) ...................................14 Brooks v. Beech Aircraft Corp., 902 P.2d 54 (N.M. 1995) ...................................14 Denny v. Ford Motor Co., 87 N.Y.2d 248, 257 (N.Y. 1995) ................................14 N.C. Gen. Stat. § 99B-6 (2007) .............................................................................15 DeWitt v. Eveready Battery Co., 550 S.E.2d 511, 517 (N.C. App. 2001) .............15 Azzarellos v. Black Bros. Co., 391 A.2d 1020, 1026 (Pa. 1978) ...........................15 ii Claytor v. General Motors Corp., 286 S.E.2d 129, 132 (S.C. 1982) ....................15 Texas Code Ann. § 82.005 (Vernon 2007) ............................................................15 Hernandez v. Tokai Corp., 2 S.W.3d 251, 256 (Tex. 1999) ..................................15 Church v. Wesson, 385 S.E.2d 393, 395 n. 6 (1989) .............................................15 Potter v. Chi. Pneumatic Tool Co., 694 A.2d 1319, 1356 (Conn. 1997)...............15 Allen v. Ministar, Inc., 8 F.3d 1470, 1479 (10th Cir. 1993) ...................................16 Baughn v. Honda Motor Co., 727 P.2d 655, 660 (Wash. 1986)............................16 Seattle-First Nat’l Bank v. Tabert, 542 P.2d 774 (Wash. 1975)............................16 D. Illinois Jurisprudence Is Firmly Rooted in the Concept of Risk-Utility for Complex Products..........................................................................................17 1. The Risk-Utility Test Has Long Been a Standard in Design Defect Cases for Complex Products................................................................................................17 Anderson v. Hyster Co., 74 Ill. 2d 364, 368 (1979).........................................17, 18 Kerns v. Engelke, 76 Ill. 2d 154, 169 (1979) ............................................17, 18, 20 Sutkowski v. Universal Marion Corp., 5 Ill. App. 3d 313, 319 (1972)..................18 Lamkin v. Towner, 138 Ill. 2d 510, 529 (1990) ...............................................18, 19 Palmer v. Avco Distributing Corp., 82 Ill. 2d 211, 219-20 (1980)........................19 Barker v. Lull Engineering Co., 573 P. 2d 443, 452 (Cal. 1978) .........................19 Soule v. General Motors Corp., 882 P.2d 298, 310 (Cal. 1994)............................19 Blue v. Environmental Engineering, Inc. 215 Ill. 2d 78, 97-98 (2005) .................19 Hansen v. Baxter Healthcare Corp., 198 Ill. 2d 420, 436 (2002) ...................19, 20 Scoby v.Vulcan-Hart Corp., 211 Ill. App. 3d 106, 112 (1991)..............................20 Calles v. Scripto-Tokai Corp., 224 Ill. 247, 260 (2007) ........................................20 iii 2. Plaintiff Should Not Be Allowed to Preclude Use of the Risk-Utility Test When Evidence Has Been Offered Supporting It. ............................................20 Kerns v. Engelke, 76 Ill. 2d 154, 169 (1979) ........................................................20 Calles v. Scripto-Tokai Corp., 224 Ill. 247, 260 (2007) ........................................20 Lamkin v. Towner, 138 Ill. 2d 510, 529 (1990) ...............................................20, 21 iv STATEMENT OF INTEREST The Product Liability Advisory Council, Inc. (“PLAC”) is a non-profit association consisting of 124 voting members, all of whom are companies in the business of designing, manufacturing and/or marketing products, including such complex products as automobiles, trucks, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, medical devices, and electronics. (PLAC also has several hundred non-voting members who are leading product liability defense attorneys.) Seven of PLAC’s member companies are headquartered in Illinois. Additional PLAC members have corporate facilities in Illinois and virtually all of PLAC’s member companies sell products in Illinois. A list of PLAC’s corporate members is attached as Tab 1 to PLAC’s Motion for Leave to File Amicus Brief. PLAC’s unique perspective and interest in this case derive from the experiences of its members, who design products in a wide range of industries and frequently face product litigation. One of PLAC’s principal missions is to file amicus curiae briefs in cases, such as this one, which affect the development of product liability law and have a potential impact on American industry, including PLAC’s members. Since 1983, PLAC has filed over 650 amicus curiae briefs in state and federal courts, including several in this Court, to present the views of product manufacturers seeking fairness and balance in the application and development of the laws of product liability, including the rules for jury instructions in cases where design defects are at issue. This brief has been written to provide the Court with ideas, arguments and insights helpful to the resolution of the case and not addressed fully by the litigants. This case is of importance to PLAC because it provides the Court with the opportunity to adopt the risk-utility test for design defect cases involving complex products as the 1 standard jury instruction in Illinois. This amicus curiae brief is respectfully submitted to address the public importance of the legal issues raised in this litigation and the policies on which they rest, apart from the immediate interests of the parties to this case. By focusing on questions regarding the history, rationales and policies underlying the proper selection of the jury instruction in cases of alleged design defect for complex products, this brief serves to fill the analytical gaps which may remain from the parties’ briefs. 2 STATEMENT OF FACTS Plaintiff tried this case against Ford Motor Company and Mazda Motor Corporation (hereinafter “Ford”) under the theory of strict liability for a design defect. See Mikolajczyk v. Ford Motor Co., 374 Ill. App. 3d 646 (1st Dist. 2007). At trial, the parties disputed the risks and utilities of a “yielding” seat, like the one in the 1996 Ford escort driven by the plaintiff. (R Vol. 12 at 34.) Plaintiff asserted that Ford should have designed the car using a “rigid” front seat and presented evidence at trial which purported to show that the risks of a yielding seat outweighed its utility, the alternative design of a rigid seat would have prevented her husband’s death, rigid seats were feasible in the 1996 Ford escort and a rigid seat should be used even though it posed a greater risk for serious neck injuries. (R Vol. 22 at 20, 6469, 89; R Vol. 21 at 74-75; R Vol. 20 at 124-26; R Vol. 9 at 245.) Ford introduced evidence showing that the yielding seat’s utility outweighed its risks, the yielding seat in the plaintiff’s car was a safe design, and no feasible alternative design could have prevented the plaintiff’s death. (R Vol. 12 at 22; R Vol. 23 at 200, 211-20; R Vol. 12 at 64.) Plaintiff never introduced any evidence showing what consumers expect in a car seat design, and plaintiff objected successfully to the admission of consumer expectations evidence by Ford. (R Vol. 9 at 245; R Vol. 14 at 68-69.) Ford proposed jury instructions based on the risk-utility evidence presented by both sides. (Supp. C Vol. 1 at 88; A-64; Supp. C Vol. at 89.) Plaintiff successfully objected to that instruction. (Supp. C Vol. at 110, 111, 113). The circuit court then instructed the jury with Illinois Pattern Instructions 400.00, 400.01 and 400.04 (2005 ed.), 3 which are based only on a consumer expectations standard and contain no mention of risk-utility or alternative feasible design. (Supp C Vol. at 113.) The jury returned a verdict for the Plaintiff, Ford appealed and the appellate court affirmed the trial judgment with the exception of directing a remittitur of the loss of society award. Mikolajczyk v. Ford Motor Co., 369 Ill. App. 3d 78 (1st Dist. 2006). At the direction of this Court, the appellate court reconsidered its decision in light of Calles v. Scripto-Tokai Corp., 224 Ill. 2d 247 (2007. Upon reconsideration, the appellate court reaffirmed the circuit court’s sole use of the consumer expectations instruction, reasoning that Illinois law allows the plaintiff to choose to proceed under either the consumer expectations or the risk-utility test, and evidence of consumer expectations is not required for the jury to deliberate under that instruction. See Mikolajczyk v. Ford Motor Co., 374 Ill. App. 3d 646 (1st Dist. 2007). After defendant Ford sought leave to appeal to this Court, review was granted and defendant Ford’s opening brief is due October 31, 2007. 4 ARGUMENT I. The Court Should Hold That the Risk-Utility Test Is the Only Proper Liability Instruction in Cases of Alleged Design Defect in a Complex Product. The crux of this case is whether the risk-utility instruction should be used to decide whether a complex product was defectively designed. A ream of legal commentary, decisions from a majority of states across the nation, and sound public policy reasons answer that question in the affirmative. The overwhelming thrust of modern law is to rely on the risk-utility test when the fact-finder has to decide whether there is liability for a defect in the design of a complex product -- as reflected in the seminal Restatement (Third) of Torts: Products Liability, § 2 (1998) (“Restatement (Third)”) and decisions by the majority of high courts in other jurisdictions across the country. Equally important, use of the risk-utility test assures that the law of strict liability in tort rests on sound public policy for the citizens of Illinois, is fair to both plaintiffs and defendants, alike, and provides a legal base that comports with the business and economic realities of product design. A. The Restatement (Third) Advances the Risk-Utility Test for Determining a Design Defect in a Complex Product.__________________ _________ A comprehensive update on the law of product liability, the Restatement (Third) reflects the debate and deliberation of distinguished practitioners, judges and legal scholars, including a balanced selection of attorneys who represented plaintiffs and defendants. When Illinois was fashioning its first approach to products liability law, it relied on the Restatement (Second) of Torts § 402A (1968). Suvada v. White Motor Co., 32 Ill. 2d 612 (1965). Now, some 30 years later, PLAC urges the court to rely on the well-reasoned Restatement (Third) for revisiting the issue of design defect. 5 The Restatement (Third) takes a markedly different approach to design defect from its predecessor, the Restatement (Second), and with good reason. The older restatement was published in 1965 when modern products liability law was in its infancy – indeed, the same year in which Illinois first announced a general approach to strict products liability law by following the Restatement (Second). Suvada, 32 Ill. 2d at 612. One notable omission in the Restatement (Second) is the lack of distinctions among categories of product defect. Whether the claim was for defective design, defective manufacturing or defective instructions or warnings, the same common definition applied. A defective product was generally defined as “any product in a defective condition unreasonably dangerous to the user or consumer or to his property . . . [even if] the seller has exercised all possible care in the preparation and sale of his product. . . .” By the mid-1990s, several decades of legal, technological and social changes had highlighted the need to refine the approach to the definition and legal tests for a product defect. In 1998, after many years of review by lawyers, judges and law professors, the American Law Institute issued the Restatement (Third). Of particular relevance here, the Restatement (Third) distinguishes among three “categories of product defect”: manufacture, design and inadequate instructions or warnings: A product: (a) contains a manufacturing defect when the product departs from its intended design even though all possible care was exercised in the preparation and marketing of the product; (b) is defective in design when the foreseeable risks of harm posed by the product could have been reduced or avoided by the adoption of a 6 reasonable alternative design . . . and the omission of the alternative design renders the product not reasonably safe; (c) is defective because of inadequate instructions or warnings when the foreseeable risks of harm posed by the product could have been reduced or avoided by the provision of reasonable instructions or warnings by the seller or other distributor, or a predecessor in the commercial chain or distribution and the omission of the instructions or warnings renders the product not reasonably safe. Restatement (Third) of Torts: Product Liability § 2 (1998). This approach to design defect hinges on the concept of “a reasonable alternative design” -- whether foreseeable risks could have been reduced or avoided by adopting a reasonable alternative design or whether the omission of the alterative design renders the product not reasonably safe. Intertwined with the concept of alterative design is the risk-utility test. As explained early in the comments, the concept of alternative design involves assessing design trade-offs, advantages and disadvantages, through a balancing of risks and utilities: [Design] defects cannot be determined by reference to the manufacturer’s own design or marketing standards because those standards are the very ones that plaintiffs attack as unreasonable. Some sort of independent assessment of advantages and disadvantages, to which some attach the label “risk-utility balancing,” is necessary. Products are not generically defective merely because they are dangerous. 7 Many product-related accident costs can be eliminated only by excessively sacrificing product features that make products useful and desirable. Restatement (Third) of Torts: Product Liability, § 2, cmt. a (emphasis added). Thus, Section 2(b) adopts the risk-utility balancing test as the standard for judging the defectiveness of product design. More specifically, the test is whether a reasonable alternative design would, at reasonable cost, have reduced the foreseeable risks of harm posed by the product and, if so, whether the omission of the alternative design . . . rendered the product not reasonably safe. Id., cmt. d As though writing a jury instruction, comment d continues: “under prevailing rules concerning allocation of burden of proof, the plaintiff must prove that such a reasonable alternative was, or reasonably could have been, available at the time of sale or distribution.” Id. B. Sound Policy Reasons Underlie Use of the Risk-Utility Test for Complex Products._________________________________ There are sound legal and public policy reasons for using the risk-utility approach when determining design defect in a complex product. For one, the approach rests on “the common sense notion that liability for harm caused by product designs should attach only when harm is reasonably preventable.” Restatement (Third) of Torts: Product Liability, § 2, cmt. f. The risk-utility test is thus fairer to both parties to the litigation, plaintiff and defendant alike. The jury reviews not only the evidence attacking design safety under a risk-free standard – the position a typical plaintiff would take - but also a balancing of alternatives, risks and utilities entailed in creating the product design. The focus on product design safety as the result of balancing alternatives also accords with the 8 long-standing strict liability rule that a manufacturer should be held accountable only for risks that are reasonably foreseeable. A manufacturer cannot insure against all harms, and even a reasonably designed product carries some dangers. For the liability system to be fair and efficient, the balancing of risks and benefits in nudging product design and marketing must be done in light of the knowledge of risks and risk-avoidance techniques reasonably attainable at the time of distribution. To hold a manufacturer liable for a risk that was not foreseeable when the product was marketed might foster increased manufacturer investment in safety. But such investment by definition would be a matter of guesswork. Id., cmt. a. Equally important, the risk-utility approach expresses a broader concern for the wellbeing of consumers – the majority of citizens who are not individual parties to a given litigation but who derive benefits from products and are affected by legal decisions about product design. That is a reason why section 2(b) emphasizes “optimal” not perfect safety in product design. The emphasis is on creating incentives for manufacturers to achieve optimal levels of safety in designing and marketing products. Society does not benefit from products that are excessively safe – for example, automobiles designed with maximum speeds of 20 miles per hour – any more than it benefits from products that are too risky. Society benefits most when the right, or optimal, amount of product safety is achieved. 9 Id In the same vein, investing in “guesswork” about safety is no benefit to consumers either. The “guesswork” is as likely to be wrong as right. And ultimately the consumer would pay the price, through increased cost of a product without any foreseeable benefit. In any event, a perfectly safe design is not a realistic goal. Prosser and Keeton, Law of Torts 699 (5th ed. 1984), in their well known commentary, make that very point in discussing the consumer expectations test: The meaning is ambiguous and the test is very difficult in application to discrete problems. What does the reasonable purchaser contemplate? In one sense he does not “expect” to be adversely affected by a risk or hazard unknown to him. In another sense he does not contemplate the “possibility” of unknown “side effects.” In a sense the ordinary purchaser cannot reasonably expect anything more than the reasonable care in the exercise of the skill and knowledge available to design engineers has been exercised. The test can be utilized to explain most any result that a court or jury chooses to reach. The application of such a vague concept in many situations does not provide much guidance for a jury. The difficulties associated with the vagaries of consumer expectations were also pointedly described by Professor Davis: Perhaps the most important criticism of the consumer expectations test as it relates to design defects is the impossibility of the task it requires: to define just what an ordinary consumer expected of the technical design characteristics of a product. While it can be assumed that consumers expect a certain level of safety, how is that level defined when it comes to 10 specific design criteria? For example, what do consumers expect of the structural characteristics that, if used, would require changes in still other aspects of the design? If the ordinary consumer can be said reasonably to expect a product to be “strong,” how strong is strong? Is a general impression of strength or quality sufficient when it comes to technical design features? If so, how is that impression measurable against the actual condition of the design feature in question. These difficult questions led many courts to reject the consumer expectations test for defective design. Davis, Design Defect Liability: In Search of a Standard of Responsibility, 39 Wayne L. Rev. 1217, 1236-37 (1993). Adopting the risk-utility test gives the Court the opportunity to preserve useful qualities of the consumer expectations test without allowing the more negative aspects of the test to dominate. In many jurisdictions, the risk-utility test may incorporate reasonable consumer expectations as one of the factors to balance. See also Restatement (Third) of Torts: Product Liability § 2(b), cmt. g (1998) (“Under Subsection (b), consumer expectations do not constitute an independent standard for judging the defectiveness of product designs.”). To abandon consumer expectations entirely would negate that consumer perceptions relate to some extent to foreseeability and frequency of risk of harm, and may, therefore, substantially influence the risk-utility balancing of design defect. But placing the factor of consumer expectations within the risk-utility test better comports with the reality that “[c]onsumer expectations standing alone, do not take 11 into account whether the proposed alternative design could be implemented at reasonable cost, or whether an alternative design would provide greater overall safety.” Id. C. The Majority of Jurisdictions Across the Country Have Adopted the RiskUtility Test to Determine Design Defect for Complex Products. Our research shows that a decisive majority of states -- at least 30 states and the District of Columbia -- require the risk-utility approach, including its emphasis on weighing design alternatives, in design defect cases. While not all of these jurisdictions apply the test to simple products, all apply the risk-utility test in cases of complex products. See Alabama: Townsend v. General Motors Corp., 642 So. 2d 411, 418 (Ala. 1994) (“plaintiff must prove that a safer, practical, alternative design was available”); Arizona: Dart v. Weibe Mfg., 709 P.2d 876, 878 (Ariz. 1985) (en banc) (“Under strict liability . . . [t]he question is whether, given the risk/benefit factors . . . and any others which may be applicable, it was unreasonable for a manufacturer with such knowledge to have put the product on the market”); California: Soule v. General Motors Corp., 882 P.2d 298, 310 (Cal. 1994) (holding that the Barker risk-utility prong is the appropriate standard for design defect, and limiting the consumer expectations test to cases involving simple products); Colorado: Comacho v. Hondo Motor Co., 741 P.2d 1240, 1247-48 (Colo. 1987) (for complex products, requiring a balancing of risks, utilities and other factors); Delaware: Mazda Motor Corp. v. Lindahl, 706 A.2d 526, 532 (Del. 1998) (“manufacturer’s failure to minimize risks, when it is reasonable to do so, will result in liability for harm caused by the unreasonably dangerous nature of the product.”); District of Columbia: Warner Fruehauf Trailer Co. v. Boston, 654 A.2d 1272, 1276 (D.C. 1995) (approving “some form of a risk-utility balancing test” for complex products) (applying 12 District of Columbia law); Florida: Radiation Tech., Inc. v. Ware Constr. Co., 445 So. 2d 329, 331 (Fla. 1983) (test “balances the likelihood and gravity of potential injury against the utility of the product, the availability of other, safer products to meet the same need,” and more); Georgia: Banks v. Ici Ams., 264 Ga. 732, 735 (Ga. 1994) (“we hereby adopt the riskutility analysis”); Indiana: Miller v. Todd, 551 N.E.2d 1139, 1141-42 (Ind. 1990) (“Defectiveness” means “claimant should be able to demonstrate that a feasible, safer, more practicable product design would have afforded better protection”); Iowa: Wright v. Brooke Group, Ltd., 652 N.W.2d 159, 169 (Iowa 2002) (“adopt[ing] Restatement (Third) of Torts: Product Liability sections 1 and 2 for product defect cases”); Kentucky: Nichols Union Underwear Co., 602 S.W.2d 429, 433 (Ky. 1980) (rejecting consumer knowledge as the only factor) (concurring opinion: “unreasonably dangerous must be determined by a social utility standard risk versus benefit”); Louisiana: Johnson v. Black & Decker U.S., Inc., 701 So. 2d 1360, 1363 (La. App. 1997) (La. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 9:2800.56 requires “the ‘risk-utility balancing test’”), writ denied, 709 So. 2d 741 (1998); Maine: Guiggey v. Bombardier, 615 A.2d 1169, 1172 (Me. 1992) (“To determine whether a product is defectively dangerous, we balance the danger presented by the product against its utility.”); Maryland: Nissan Motor Co. v. Nave, 129 Md. App. 90, 118 (Md. App. 1999) (“In design defect cases, Maryland courts employ the ‘risk/utility’ balancing test to determine whether a specific design is unreasonably dangerous.”), cert. denied, Nave v. Nissan Motor, 357 Md. 482 (2000); Massachusetts: Uloth v. City Tank Corp., 384 N.E.2d 1188, 1193 (Mass. 1978) (case for jury if “the plaintiff can show an available design modification which would reduce the risk without undue cost or interference with the performance of the machinery”); Michigan: Prentis v. Yale Mfg. Co., 421 Mich. 670, 13 14 691 (Mich. 1984) (adopting “risk-utility test in products liability actions against manufacturers of products, where liability is predicated upon defective design.”); Minnesota: Forster v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., 437 N.W.2d 655, 661 (Minn. 1989) (“In this state we use a risk-utility balancing test to determine if a product liability claim will lie for a design defect.”); Mississippi: Miss. Code Ann § 11-1-63(f) (2003) (requiring proof, among other things, of “a feasible design alternative that would have to a reasonable probability prevented the harm”); see also Williams v. Bennett, 921 So. 2d 1269, 1276 (Miss. 2006); Montana: Rix v. General Motors, 723 P.2d 195, 202 (Mont. 1986) (“[a] design is defective if at the time of manufacture an alternative designed product would have been safer than the original designed product and was both technologically feasible and a marketable reality”); New Hampshire: Thibault v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., 395 A.2d 843, 846 (N.H. 1978) (adopting a risk utility analysis for design defect, “weighing utility and desirability against danger”); New Jersey: N. J. Rev. Stat. § 2A:58c-3a (2007); see also Diluzio-Gulino v. Daimler Chrysler Corp., 897 A.2d 438, 441 (N.J. Super App. Div. 2006) (“A plaintiff asserting design defect in products liability action must prove, under risk-utility analysis, existence of alternate design that is both practical and feasible, and ‘safer’ than that used by manufacturer.”); New Mexico: Smith v. Bryco Arms, 33 P.3d 638, 644 (N.M. App. 2001) ( “Determining whether a product design poses an unreasonable risk of injury also involves considering whether the risk can be eliminated without seriously impairing the usefulness of the product or making it unduly expensive”) (citing Brooks v. Beech Aircraft Corp., 902 P.2d 54 (N.M. 1995); New York: Denny v. Ford Motor Co., 87 N.Y.2d 248, 257 (N.Y. 1995) (design defect test includes multiple factors of “both risks and benefits”); North 15 Carolina: N.C. Gen. Stat. § 99B-6 (2007) (requiring proof that manufacturer “unreasonably failed to adopt a safer, practical, feasible and otherwise reasonable alternative design” that would have prevented or “substantially reduced the risk of harm”); see also DeWitt v. Eveready Battery Co., 550 S.E.2d 511, 517 (N.C. App. 2001); Pennsylvania: Azzarellos v. Black Bros. Co., 391 A.2d 1020, 1026 (Pa. 1978) (proper approach is “a balancing of the magnitude of the risk against the utility of the risk”); South Carolina: Claytor v. General Motors Corp., 286 S.E.2d 129, 132 (S.C. 1982) (in determining a design defect, “we have another of the law’s balancing acts and numerous factors must be considered, including the usefulness and desirability of the product, the cost involved for added safety, the likelihood and potential seriousness of injury, and the obviousness of danger”); Texas: Texas Code Ann. § 82.005 (Vernon 2007) (in products liability action for design defect, burden on plaintiff to prove “there was a safer alternative design”); see also Hernandez v. Tokai Corp., 2 S.W.3d 251, 256 (Tex. 1999) (discussing “risk-utility analysis” as a “requisite element of a cause of action for defective design”); West Virginia: Church v. Wesson, 385 S.E.2d 393, 395 n. 6 (1989) (“‘unsafe’ imparts a standard that the product is to be tested by what the reasonably prudent manufacturer would accomplish in regard to the safety of the product, having in mind the general state of the art of the manufacturing process, including design, labels and warnings, as it relates to economic costs, at the time the product was made”). Beyond the jurisdictions that have plainly adopted a risk utility standard, some states continue to use a purported “consumer expectations” test but in fact have converted that test to a risk-utility standard. See, e.g., Connecticut: Potter v. Chi. Pneumatic Tool Co., 694 A.2d 1319, 1356 (Conn. 1997) (“We find persuasive the reasoning of those 16 jurisdictions that have modified their formulation of the consumer expectations test by incorporating risk-utility factors into the ordinary consumer expectations analysis.”); Utah: Allen v. Ministar, Inc., 8 F.3d 1470, 1479 (10th Cir. 1993) (applying Utah law) (affirming that in strict liability design defect cases, plaintiff bears “the burden of showing that any alternative, safer design, practicable under the circumstances and available at the time”); Washington: Baughn v. Honda Motor Co., 727 P.2d 655, 660 (Wash. 1986) (en banc) (“While usually called a ‘consumer expectations’ test, the Tabert rule actually combines the consideration of consumer expectations with an analysis of the risk and utility inherent in a product’s use.”) (citing Seattle-First Nat’l Bank v. Tabert, 542 P.2d 774 (Wash. 1975). Also of note, virtually all of the nation’s densely populated industrial states have adopted the risk-utility/alternative feasible design as a required test for complex products. Thus, risk-utility is the test in California, Georgia, Florida, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Texas. In short, the trend among the states is to use the risk-utility test to determine design defect in a complex product. PLAC urges the Court to specifically adopt the riskutility standard in Illinois for complex products, and allow the full range of affected persons – plaintiffs and defendants in litigation, consumers, and persons designing or marketing products in Illinois – to enjoy the advantages of the modern rule. 17 D. Illinois Jurisprudence Is Firmly Rooted in the Concept of Risk-Utility for Complex Products._________________________________________ 1. The Risk-Utility Test Has Long Been a Standard in Design Defect Cases for Complex Products. Illinois is no stranger to use of the risk-utility test, especially in the context of proof of a feasible alternative design. It would be entirely consistent with the development of Illinois law for the Court to hold squarely that the risk-utility test is required in design defect cases where the product is complex. In Anderson v. Hyster Co., 74 Ill. 2d 364, 368 (1979), the court announced that a design defect may be proved “by evidence of the availability and feasibility of alternative designs at the time of its manufacture, or that the design used did not conform with the design standard of the industry, design guidelines provided by authoritative voluntary association or design criteria set by legislation or governmental regulation.” That same year, the Court explained the merits of a similarly-premised balancing test in Kerns v. Engelke, 76 Ill. 2d 154, 169 (1979) (ruling on proper standard for strict liability design defect of a complex product, the power takeoff assembly of a “long-hopper” forage blower): the “plaintiff must present pertinent evidence, such as an alternative design, which is economical, practical and effective, to the fact finder, who determines whether the complained-of condition was an unreasonably dangerous defect.” In the development of product's liability principles design alternatives are appropriately considered whether reasonable care is the basis of liability or where liability is predicated upon strict tort liability. . . The possible existence of alternate designs introduces the feature of feasibility since a manufacturer's product can hardly be faulted if safer alternatives are not 18 feasible. In this connection feasibility includes not only the elements of economy, effectiveness and practicality but also the technological possibilities viewed in the present state of the art. Id. (quoting Sutkowski v. Universal Marion Corp., 5 Ill. App. 3d 313, 319 (1972).). Kerns approved this instruction, given over the plaintiff's objection: There is no duty upon the manufacturer of the [product] to manufacture the product with a different design, if the different design is not feasible. Feasibility includes not only elements of economy, effectiveness and practicality, but also technological possibilities under the state of the manufacturing art at the time the product was produced. Id. at 164. Kerns also emphasized that in cases of design defect, the manufacturer could not be held to a risk-free standard of liability, another benefit of weighing the risks and utilities of the allegedly defective design: A manufacturer is not required to produce a product which represents the “ultimate in safety.” Rather, we premise liability on our finding that not only does the evidence support the jury's conclusion that a safer, economical and feasible design existed, but it also supports the conclusion that safe use of [defendant’s] design was impractical, resulting in a foreseeable misuse. Id. at 166 (citations omitted). Following Anderson and Kerns, some Illinois courts broadened the test for design defect to allow the plaintiff to prove a defect either with the risk-utility test or the consumer expectations test. The approach came to a head in Lamkin v. Towner, 138 Ill. 19 2d 510, 529 (1990) (citing Palmer v. Avco Distributing Corp., 82 Ill. 2d 211, 219-20 (1980) and Barker v. Lull Engineering Co., 573 P. 2d 443, 452 (Cal. 1978)). Looking principally to the test and reasoning of California’s Barker decision, Lamkin allowed the plaintiff to rely on either the consumer expectations or risk-utility test for proving design defect – although Lamkin also offers that the defendant is allowed to prove that “on balance the benefits of the challenged design outweigh the risk of danger inherent in such designs.” 138 Ill. 2d at 529. Since Lamkin was decided, California has abandoned the consumer expectations prong for design defect cases involving a complex product and now requires the risk-utility test for complex products. See Soule v. General Motors Corp., 882 P.2d 298, 310 (Cal. 1994) (holding that the Barker risk-utility prong is the appropriate standard for design defect, and limiting the consumer expectations test to cases involving simple products). More recently, this Court returned to its original emphasis on a risk-utility standard for strict liability design defect cases. In Blue v. Environmental Engineering, Inc. 215 Ill. 2d 78, 97-98 (2005) (negligence claim for defective design of an industrial trash compactor), the court compared the strict liability standard with the standard for negligence cases of defective product design (the actual claim before the court): “[S]trict liability focuses on the product and only requires proof that the benefits of the challenged design do not outweigh the risk of danger inherent in such designs, that the alternative design would have prevented the injury, and that the alternative design was feasible in terms of cost, practicality and technology.” Id. (citing Hansen v. Baxter Healthcare Corp., 198 Ill. 2d 420, 436 (2002).) Blue also noted a distinction made in earlier Illinois decisions between simple and complex products, and reinforced that complex products 20 require the risk-utility test. 215 Ill. 2d at 109-112, citing Scoby v.Vulcan-Hart Corp., 211 Ill. App. 3d 106, 112 (1991) (designs of simple products showing the “obvious nature of any danger” would not be subject to the “danger-utility” test) and Hansen, 198 Ill. 2d at 436-38 (acknowledging the Scoby exception for simple products). The standard set forth in Kerns came full cycle earlier this year in Calles v. Scripto-Tokai Corp., 224 Ill. 247, 260 (2007). Rejecting a per se rule excepting simple products with open and obvious dangers from the risk-utility test, Calles’ plain implication was that the risk-utility test was the only proper standard for complex products. That meaning was reinforced by Calles’ detailed explanation of the “numerous factors” that could be used under the risk-utility test. Id. at 263-266. 2. A Plaintiff Should Not Be Allowed to Preclude Use of the Risk-Utility Test When Evidence Has Been Offered Supporting It. The combination of Kerns culminating in Calles suggests another important facet of proper jury instructions when the claim is for a defective design: the plaintiff should not be allowed to preclude the jury from weighing risk-utility factors. Lamkin, known for allowing proof of a design defect through either the consumer contemplations test or the risk-utility test, actually did not even consider the issue of a jury instruction. Instead, it reviewed only the merits of granting pre-trial dispositive motions dismissing the claims. And even Lamkin approved a standard that allowed proof of whether “on balance the benefits of the challenged design outweighs the risk of danger inherent in such designs.” 138 Ill. 2d at 510. The situation in the instant case is virtually unique among Illinois decisions and the Court should act quickly to reverse it. Research does not disclose another product liability decision in Illinois, involving a complex product, where the Court received 21 evidence of a product’s risks and benefits from both sides, including the feasibility of an alternative design, and then would not allow the jury to consider a risk-benefit approach to decide whether the product was defectively designed. Sanctioning this approach would be the worst application of the Lamkin approach – even assuming that Lamkin fairly represents today’s product defect law in Illinois. Allowing a plaintiff to select the legal standard applicable to cases for a complex product imposes an unacceptable element of surprise and arbitrariness, as well as a decidedly uneven playing field for the defendant. The problem is compounded when the plaintiff is permitted to choose consumer expectation as the sole legal standard and ignore extensive evidence on riskutility. CONCLUSION The confusion created by the decision below shows how critical it is for this Court to articulate a standard for design defect that will give the necessary guidance for determining how a plaintiff can prove a prima facie case of design defect for a complex product and, equally important, what standard a jury should use to evaluate the evidence. This case presents the opportunity for the Court to sanction an instruction with which to guide juries to intelligent, reasonable decisions without the use of vague, meaningless rhetoric. 22 WHEREFORE, amicus Product Liability Advisory Council, Inc. urges the Court to hold that the risk-utility test is the proper jury instruction in Illinois product liability actions when liability is predicated upon defective design of a complex product. Respectfully submitted, /s/ Stephanie A. Scharf Stephanie A. Scharf Mary Ann Becker Schoeman Updike Kaufman & Scharf 333 W. Wacker Drive Suite 300 Chicago, IL 60606 (312) 726-6000 On behalf of amicus curiae Product Liability Advisory Council, Inc. 23 No. 104983 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF ILLINOIS Connie Mikolajczyk, Individually and as Special Administrator Of The Estate Of James Mikolajczyk, Deceased, Plaintiffs-Appellees, vs. Ford Motor Company; Mazda Motor Corporation, Defendants-Appellants, And William D. Timberlake, Defendant. ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) ) Appeal From the Appellate Court Illinois, First District, No.: 1-05-3133 The Honorable James P. Flannery Presiding CERTIFICATE OF COMPLIANCE I certify that this brief conforms to the requirements of Illinois Supreme Court Rules 341(a) and (b). The length of this brief is pages. /s/ Stephanie A. Scharf Stephanie A. Scharf Mary Ann Becker Schoeman Updike Kaufman & Scharf 333 W. Wacker Drive, Suite 300 Chicago, IL 60606 (312) 726-6000 24