Vol 5 - Fort Hays State University

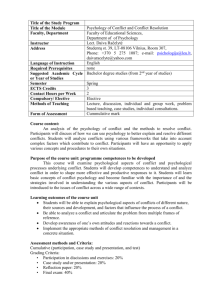

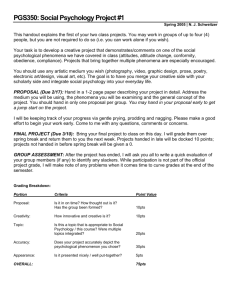

advertisement