WHAT THE LAW PROFESSOR

SAID

ABOUT DEEDS

BY PATRICK J. REVILLE, Esq.

DEDICATION

To My Wife and Partner forever.

All rights reserved under the international and Pan-American

copyright conventions.

First published in the United States of America.

All rights reserves. With the exception of brief

quotations in a review, no part of this book may be reproduced

or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic or

mechanical (including photocopying), nor may it be stored in

any information storage and retrieval system without written

permission from the publisher.

DISCLAIMER

The advice contained in this material might not be suitable for

everyone. The author designed the information to present his

opinion about the subject matter. The reader must carefully

investigate all aspects of any business decision before

committing him or herself.

The author obtained the

information contained herein from his own personal experience

but he neither implies nor intends any guarantee of accuracy.

The author, although in business of giving legal and accounting

advice is not giving such advice through this writing, and

nothing contained herein is intended to create attorney-client

relationship with the reader. Should the reader need such

advice, he or she must seek services from a competent, retained

professional. The author particularly disclaims any liability,

loss or risk taken by individuals who directly or indirectly act

on this information contained herein. The author believes the

advice presented here in sound, but readers cannot hold him

responsible for either the actions they take or the result of those

actions.

Printed in U.S.A.

Copyright © 2009 by Patrick J. Reville

About The Author

Patrick J. Reville graduated from Iona College in New

Rochelle, N. Y., with a B.B.A. degree in Accounting. Three

years later, he was awarded the degree of J.D. from Fordham

University School of Law in N.Y.C. In the spring of 1969,

(Professor to be) Reville was admitted to the N.Y.S. Bar, and

immediately embarked upon the private practice of law and

accounting.

Brief teaching stints in the NYC public school system

and at Mercy College in Dobbs Ferry, N.Y., were followed by

an appointment at Iona College as an Adjunct Professor Of

Business Law in 1975. Since that time, Professor Reville has

risen through the ranks at Iona to become a tenured Associate

Professor Of Business Law, was awarded the Pro Opereis

award for twenty years of full time service, and was most

recently awarded the Bene Merenti award for thirty years of

full time service at that institution.

Professor Reville has practiced what he has taught,

engaging in the General Practice Of Law and Accounting in

New Rochelle, N.Y. for almost forty years.

For many of those years, The Professor has taught the

Real Estate Salesperson’s and Broker’s pre-licensing courses

throughout Westchester County, N. Y., and has been a

practicing licensed Real Estate Broker during the majority of

that time. Professor Reville has been active in Real Estate as

(a) Broker; (b) Landlord; (c) Investor; (d) Accountant; and (e)

Attorney for Landlords, Tenants, Purchasers, Sellers, Lenders

and Title Insurers.

Professor Reville has also represented thousands of

individuals accused of committing criminal acts, and

volunteered his time to represent the indigent in the criminal

justice system. He is a Justice Of The Peace in the Town of

Ridgefield, CT.

Over the years, The Professor has written and spoken

often on numerous legal topics. To illustrate the items and

concepts addressed on a regular basis in front of the college

classroom on a semester to semester basis, Professor Reville

brings his experiences from private practice and the courtroom

to the classroom to enhance his lectures with colorful reality.

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Get a Lawyer!

INTRODUCTION

This book and the information contained herein

are not to be considered Legal Advice. There are

three (3) rules to remember when tackling a legal

problem:

1. GET A LAWYER; 2. GET A

LAWYER; and, 3. GET A LAWYER. Now, this

may sound a little self-serving, or a promotion for the

hiring of attorneys. NOT TRUE. In fact, it is the only

legal advice contained in this writing, and I cannot

emphasize it enough. Over the past forty (40) years, I

have encountered countless situations where

heartache, frustration and even financial ruin could

have been avoided by just a little bit of good legal

advice.

The old saying, that “An Ounce Of

Prevention…” Well, you know the rest of that axiom.

This writing is about Information, plain and

simple. You have also probably heard the saying, that

“Knowledge is Power.” NOT (Totally) TRUE. It has

been explained to me, and I have learned to accept,

that it is the USE of knowledge that is powerful. It is

my hope, that you, the reader, will use the knowledge

I am attempting to pass on to you to for your

protection and benefit.

This book is not about making lawyers out of

its readers. It is not about enabling its readers to

engage in legal transactions without the need and

costs of sound legal advice. It is not about preparing

its readers to challenge members of the legal

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

An Ounce of Prevention…

profession, or play “gotcha” with those who are

sincere in their efforts to guide you appropriately

through the legal maze of a transaction or problem. It

is certainly not about trying to show you “How To

Make A Million Dollars In Real Estate Or Business In

Thirty Days, With No Money Down, And Without

Ever Paying A Legal Fee.” It is about making you

aware of the terminology, meaning and usage of basic

concepts of the law as they relate to a particular field.

You can use the knowledge and information contained

in the following pages to prepare you to be a better

listener, student and participant in matters that affect

you from a legal standpoint. To paraphrase a

longtime slogan used to promote a New York

business: In The Legal Profession, An Educated

Consumer Is Our Best Client.”

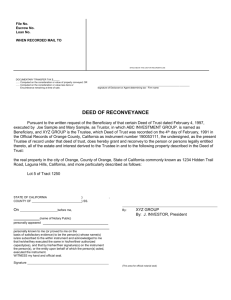

1. A DEED. WHAT IS IT?

A Deed is a Real Estate Instrument. It is a

piece of paper. It is used to convey title, ownership

and rights in real property. There are basically only

two (2) types of property: (1) real property; and, (2)

personal property. These are separate, distinct, and,

for the most part, mutually exclusive concepts.

Accordingly, the laws that govern real property and

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Awareness is the Key

personal property are also, for the most part, separate,

distinct and mutually exclusive. Here, with deeds, we

are talking about real property and the real property

law governing their use.

By the nature of the beast, there are no oral

deeds. Real Property has been around a long time,

and it is fairly settled in American jurisprudence that

the system does not want the headaches and potential

fraud related to oral conveyances of Real Property.

You can always find some narrow, obscure exception

to any accepted way the law works, but, for the most

part, we are dealing in this book with the deed as an

instrument, and hence, a written document.

It should also be noted that Real Property is

local in nature, and although the law(s) that are

applied to it throughout the United States are similar

in content, there may be local variations. Remember,

they don’t preach “Location, Location and Location”

for no good reason.

2. WHAT ARE THE BASIC REQUIREMENTS?

There are many requirements for a valid

conveyance by deed. But, to keep it simple for

starters, let’s say that there are two (2) basic

requirements: (1) Execution; and, (2) Delivery. A

third requirement would be: Acceptance.

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Knowledge is NOT Power,

the USE of Knowledge Is

1. Execution. This word, of course, has a

number of meanings, even in the law. If you heard

that a death row inmate was executed last night, you

would presume that he/she was put to death by the

criminal justice system. You might hear someone

ask: “Did he execute the Will while in his right

mind?” you would probably be asking if he signed the

Will being mentally competent. Even in a contract

setting, an executed contract might mean (a) signed;

or, (b) fully performed. Here, with a deed, by

executed, we mean signed.

Q.: Signed by whom? A.: By the grantor, or

the grantor’s agent.

Q.: Who is the grantor? A.: The grantor is the

name/title given to the transferor of an interest in real

property, who signs a deed. The grantor may be a

vendor (a seller) of real property. The grantor may be

a donor (a giver) of real property. The grantor may

be a settlor (a person creating or funding a trust). It

just happens that the generally accepted label for the

person or party that conveys real property by deed is

known as the grantor.

Q.: Who is the grantor’s agent? A.: Most

things in the law that a person can do, can be done

through an agent. If a person is going to have a deed

signed by his or her agent, most states require that the

authority to so sign a deed must be reduced to a

writing, in the form of a Power Of Attorney

(discussed later herein). A Corporation is a person for

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

An Educated Consumer is

the Best Client

most applications of the law, and a Corporation

would sign a deed as grantor by having someone, for

example, its President, sign as agent for the

Corporation. If a corporate officer was signing a deed

for a corporation, a Power Of Attorney is not

generally required, but it would be wise to have some

proof or certification of the authority of the corporate

officer to so sign.

Q.: Can there be multiple grantors? A.: Yes.

If two or more parties are in title (discussed later

herein)/owners of the property, they each must sign

the deed, either personally or by agent, to make the

conveyance of the full ownership effective. If there

are multiple owners of the property, a signature by

less than all owners only conveys the signing

grantor’s interest in the property.

Q.: Can a spouse sign over his/her spouse’s

interest in the property? A.: NO, not without an

appropriate Power Of Attorney from the “absent”

spouse. A spouse is NOT an automatic agent for a

spouse, particularly in Real Property matters.

Q.: HOW should a grantor sign his or her

name? A.: A wise and common practice would be

for a person to sign his or her name exactly as it

appeared on the deed that he/she received when they

became the owner. This would be ascertained in the

course of a title search (discussed later herein). For

example, if John Paul Smith received a deed

conveying property to him, and the deed cited him as

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Two Types of Property:

Real Property

And Personal Property

“John Paul Smith” as grantee (discussed later herein),

he would sign a deed as grantor: “John Paul Smith”,

and not as “John Smith”, “John P. Smith”, “J. P.

Smith”, “Johnny Smith”, or “Smitty”, etc. As a very

technical or legal matter, however, if John Paul Smith

did sign his name in any of those other formats, it

would legally convey his interest in the property, but

it likely could become problematic in the future

because the issue might be raised as to whether the

person who signed the later deed was in fact the same

person who was the grantee in the prior deed. This

problem/issue might be resolved by an additional

reference in the later deed (discussed later herein).

Q.: WHERE (on the document) does the

grantor sign? A.: Most documents should be and are

signed at the end of the document. It is no different

with a deed. Traditionally, a deed is signed by the

grantor at the lower right portion of the last page of

the deed, on a line over the printed/typed name of the

grantor.

Q.: MUST the grantor sign on a line? A.: NO.

Q.: MUST the grantor’s name be printed/typed

below the signature? A.: NO.

Q.: What color ink needs to be used for a

grantor’s signature? A.: Most states do not specify a

particular color of ink for a grantor’s signature, and

even allow a signature by pencil (not advised). Some

practitioners prefer blue ink, because it is easier to

determine that a document is an original, since some

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Basic #1: Execution

copiers copy black ink so well it is difficult to

determine if a document is a copy or an original. Yet

other recording officers (discussed later) try to

impose a “black ink” only rule for a grantor’s

signature. Local custom or rule(s) should be adhered

to. When in doubt, use black ink.

Q.: Must a grantor’s signature be witnessed?

A.: Generally, NO, but it is common to have a

witness sign to the left of a grantor’s signature, just in

case at some later date the authenticity of the grantor’s

signature comes into question.

Q. Must a grantor’s signature be notarized to

make a deed valid? A.: Generally, NO, but, again, it

is common and customary to notarize a deed in the

form of an acknowledgement. A Notary Public,

Commissioner Of Deeds or Justice Of The Peace

usually is the party that performs this act. Also, a

deed will typically not be accepted for recording (see

below) unless duly acknowledged.

Q.: WHAT is Recording? WHO does this,

and WHY?; and is recording a deed necessary to

make a conveyance valid?

A.: Recording is a process whereby a recording

officer (New York—County Clerk where the property

is located, except in NYC, where it is the Office Of

The City Register; Connecticut—Town Clerk where

the property is located, etc.) takes in an original

document (deed, mortgage, etc.), stamps and clocks in

the document with date and time, collects appropriate

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Signed by the Grantor,

Or the Grantor’s Agent

fees, makes a COPY of the document as so clocked

in, returns the original to the presenting party, and

keeps the copy on record for public examination.

The reason to record any real estate document,

including a deed, is to give NOTICE To The World

that the parties cited in the document have engaged in

a transaction that affects their rights to the property.

This is a form of constructive notice, where the public

is deemed to be aware of what is on the public record,

even though the have not actually seen the recorded

document. A deed does NOT have to be recorded to

make the conveyance valid or legal, but failure to

record a deed can cause ownership and title problems

later. (See discussion of Title Search and Title

Insurance later herein.)

2.

Delivery.

To effect a valid

conveyance, a deed must be delivered to the grantee

or the grantee’s agent. This can be done in person, by

mail (regular or express) or even delivering the deed

to a person of suitable age and discretion acting on

behalf of the grantee. No Power Of Attorney is

required to act on behalf of a grantee in receiving a

deed.

Q.: WHO is the grantee? A.: The grantee is

the transferee, and possibly a vendee (purchaser),

donee (recipient of a gift), or Trustee (party named in

a Trust to receive, hold and manage property).

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Basic #2: Delivery

3. Acceptance. Acceptance of the deed

by the grantee is required. However, acceptance by

the grantee is typically presumed, that is, if a grantee

bargained for the transfer, and was presented with an

appropriately executed deed, why would not the

grantee accept? Good question. On the other hand,

suppose the transfer was a gift, and the grantee

rejected the gift of real property, for whatever the

reason. Then, the rejection of the tendered delivery of

the deed would cause the transfer to be ineffective.

Even if the transaction was not a gift, and the grantee

had previously bargained for the transfer, it is possible

that the grantee might decide to back out of the

transaction, and face whatever legal consequences

there may be. So, while it is typically presumed that

the grantee accepts a tender of delivery of a deed, it

may not be necessarily so.

3.

WHAT ARE THE OTHER/SPECIFIC

REQUIREMENTS OF A VALID DEED?

To review the various other/specific

requirements of a valid deed, it may serve a person

well to start at the top of a typical deed, and work

down through the layout and content usually

embodied therein.

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Delivered to the Grantee

Or the Grantee’s Agent

1. The Date. The top of a typical deed

usually has language such as: “THIS INDENTURE,

made the______ day of _______________,

_________...” The date signed or delivered would be

filled in accordingly. If the date is left blank, or

partially blank, this is a mistake, but typically not a

fatal mistake. It may cause problems later proving

just exactly did the conveyance take place.

Remember, even if the deed is dated when signed, it is

not effective to convey the property unless and until

delivered (see above).

2. Description Of The Parties.

The deed will then usually have language as to who

the conveyance is between. Often, the grantor is cited

first, and often referred to as “…party of the first

part…”, and the grantee is then cited, and often

referred to as “…party of the second part…” The

grantor(s) and grantee(s) should be clearly identified

(normally name and address will suffice, but P. O.

Box designations have been known to be rejected by

recording officers. If a party was known in the past

by another name, it is a good idea to cite the party as

the current name, “f/k/a (formerly known

as)______________”; or, if known now by a different

name, cite as the prior name, “n/k/a (now known

as)_____________”. Additional clarification might

be inserted in the body of the deed by language such

as: “Such party of the first part being the same person

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Basic#3: Acceptance

cited as Grantee in Deed Dated _________and

recorded in the Office Of The County Clerk of The

County Of Erie, Division of Land Records, in

Liber_____

Page________

(or

Control#______________)

on

_____________,

whereby said party of the first part herein became the

owner of the subject property conveyed herein.”

3. A Recital Of Consideration. The

actual price paid for a conveyance typically does NOT

have to be inserted in a deed (although it may be),

except for some specialty deeds (see Types Of Deeds,

discussed later herein). However, there must be some

recital of consideration, for example: “…in

consideration of ten ($10.00) dollars and other

valuable consideration…”, or, “ in consideration of

Four Hundred Forty-One Thousand ($441,000.00)

Dollars…”

4. Words Of Conveyance. There must

be some words of transfer or conveyance, such as:

“…the party of the first part does hereby grant and

release unto the party of the second part, the heirs or

successors and assigns of the party of the second part

forever…”

5. Legal Description Of The Property

Conveyed. There are a number of ways the property

being conveyed can be effectively described. (See:

Legal Descriptions, later herein.) Before the actual

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

You Need to HAVE Title

to PASS Title

Legal Description is inserted in the body of the deed,

there is often language that reads: “ALL that certain

plot, piece or parcel of land, with the buildings and

improvements erected, lying and being in the…”

Recent common practice has been to insert the

following language just after that introductory clause

the following wording:

“SEE SCHEDULE A

ATTACHED HERETO”, and then attach a separate

page, entitled “SCHEDULE A” to the body of the

deed. The Schedule A description can be photocopied

from a prior deed or title report (discussed later

herein) without requiring re-typing or printing the full

legal description in the body of the deed. This device

or practice saves time and greatly reduces the chance

of errors in the legal description.

6. Habendum Clause. This cause

typically reads: “TO HAVE AND TO HOLD the

premises herein granted unto the party of the second

part, the distributees or successors and assigns of the

second part forever.”

By using this standard

language, the type of estate/ownership in real property

being conveyed, cited in the language of the granting

clause above in the deed, is confirmed. The latin

word, habeo, means to have, hold or possess.

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Don’t Forget the Date

7.

“Together With”, “ Excepting

Therefrom” and/or “Subject Thereto” Clauses.

Here clauses can be and usually are added that will

include rights to streets and roads abutting the

premises, language of appurtenances (discussed later

herein), and any exclusions of or limitations on the

property rights being conveyed. Language of any

easement(s) (discussed later herein) affecting the

property conveyed might be inserted here.

8. Covenants and Restrictions. Any

Covenants and /or Restrictions affecting the subject

property would be inserted. These will be discussed

later herein.

9.

Required Statutory Language.

Some States require some additional language

according to applicable State Law(s).

10. Customary Verbiage Preceding

Signature(s). At the end of the deed, there is often

language that reads: In Witness Whereof, the party of

the first part has duly executed this deed the day and

year first above written.”

11.

Above.

Signature(s) of Grantor(s).

See

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Identify the Parties

12. Capacity of the Grantor. It is assumed

that the grantor is someone who is legally capable of

conveying real property. By State law, this would

typically mean someone who has reached eighteen

(18) years of age, and who is mentally competent. In

the United States, we operate under a presumption of

sanity, unless proven otherwise. If it turned out by

clear and convincing evidence that the grantor was not

“of his right mind” at the time of the execution of the

deed, the deed, if attacked in Court, would fail to

effectuate a transfer of title. The burden of proof of

the incapacity would be on the party who attacked the

capacity of the grantor. If the grantor had previously

been declared mentally incompetent by a Court of

competent jurisdiction, then any purported

conveyance by that person, who had not been

judicially relieved of that incompetency would be

ruled void. If a party was ruled incompetent, a Court

could appoint a guardian or conservator of the

incompetent party, who then would be the appropriate

person to execute a deed on behalf of the incompetent

party.

4. THE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

As stated above, it is customary to have certain

important documents, including deeds, notarized.

The notarization of a deed takes the form of an

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Describe the Property

acknowledgement.

The language of a typical

acknowledgement

has

been

expanded

and

standardized over the years, but it pretty much states

that the person(s) who signed the within instrument

(the grantor(s) in the case of a deed), personally

appeared

before

the

party

taking

the

acknowledgement (a Notary Public, Commissioner Of

Deeds, Justice Of The Peace, etc.) and acknowledged

to the person taking the acknowledgement that

he/she/they executed/signed the within document in

their individual or representative capacity(ies). The

person taking the acknowledgement must be careful to

in fact have the acknowledging person(s) appear

before him, and, because of numerous fraudulent deed

signings, valid photo identification should be viewed

by the acknowledging officer, and, for their protection

and compliance with state and/or federal law, a COPY

of the proofs of identity should be retained by the

acknowledging officer along with a copy of the

document acknowledged.

5. TYPES OF DEEDS

There are a number of different types of deeds, and

they vary a bit from State to State. Local trade or

custom will also usually dictate which form of deed is

used in any given circumstance. Discussion of some

of the most common forms of deeds follows.

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Recital of Consideration

1. The Full Covenant and Warranty Deed,

sometimes called a Warranty Deed. This deed, like

any other discussed below, must conform to all the

requirements of a valid deed discussed hereinabove,

but, in addition, it typically contains a series of

covenants (promises) made by the grantor(s).

(a) Covenant of Seisin. By this, the

grantor warrants that he has the rightful ownership

and possession of, and has the right to convey title to,

the property.

(b) Covenant of Quiet Enjoyment. This

does not mean that the grantee will have a quiet,

tranquil enjoyment of the property in a literal sense,

but that the title will withstand attack(s) by third

parties claiming that they have a superior right to the

property.

(c) Covenant Against Encumbrances.

The grantor hereby covenants that the property is free

from liens or other encumbrances (claims, taxes,

charges, rights of others) against the property.

(d) Covenant Of Further Assurances.

The grantor covenants to secure any proofs,

documents, releases that may be necessary to make

the title good/clear.

(e) Covenant Of Warranty Forever. This

means that the grantor promises to stand behind the

validity of the title forever.

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Words of Conveyance

On its face, the Full Covenant and Warranty

Deed seems like the preferred deed of choice for the

grantee. Yet, common practice has it that this type of

deed is often not used. Why not? For a few reasons.

First, when a grantor/seller transfers property, they

usually want to be finished with it, without lingering

potential problems. Hence, the grantor does no want

to make promises that could come back to haunt (and

cost) him. Secondly, once a grantor conveys, it

becomes difficult for a grantee to later seek out, find,

and practically enforce promises against a former

owner. Thirdly, it is very common for a potential

grantee (and for that matter, a potential lender) to

obtain Title Insurance (discussed below) issued by an

insurance company regulated by State law. If a

problem of title does crop up, the Title Insurance

Company, with required reserves, can be required to

step up and provide a fountain of remedy for the

insured grantee to drink from.

2. The Bargain and Sale Deed(s). This deed,

as stated above, would contain all the legal

requirements, but it might contain a Covenant

Against Grantor’s Acts. There would not be the five

(5) promises contained in a Warranty Deed, but there

would be a single covenant that “…the party of the

first part covenants that the party of the first part has

not done or suffered anything whereby the said

premises have been encumbered in any way

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

To Have and To Hold…

whatsoever, except as aforesaid.” This, in effect is a

limited covenant by the grantor. Yet, again as a

practical matter, the use of Title Insurance (discussed

below) will minimize any real difference between this

type of deed and the Full Covenant and Warranty

Deed.

There may be a Bargain and Sale Deed Without

The Covenant Against Grantor’s Acts. It is generally

concluded that a grantor, while not expressly making

the abovementioned covenant, would by implication

make same.

3. The Quitclaim Deed. This deed uses

conveyance language such as: “…does hereby remise,

release and quitclaim unto the party of the second

part…” No promises or covenants regarding title are

made with this deed. Yet, if the grantor has title, the

grantee gets title. Again, the use of Title Insurance

will minimize the risks in taking a deed with or

without promises.

This type of deed is often used for conveyances

by gift, between spouses and other family members,

and where there is some issue of title that needs to be

clarified. If there is some claim of title made to real

property, and the parties wish to “clear the cloud on

title”, a quitclaim deed can be employed without the

granting party making any representations or promises

as to the right(s) he or she is relinquishing. It should

be noted, however, that even though a quitclaim deed

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Covenants and Restrictions

is commonly used between family members, if the

transaction is in fact a purchase, care should be given

to observe the advice below regarding Title Insurance.

In fact, even if the intra-family transfer is in the nature

of a gift, it would be wise for the grantee to consider

the protections of the title search/title insurance path,

for there may be some defect in title that the family

member grantor is unaware of. It would be much

easier to correct/alleviate any such problem(s) sooner

than later.

(4) The Executor’s or Administrator’s Deed.

If a property owner dies with a valid will that is

probated, the Surrogate’s/Probate Court will likely

confirm an Executor named in the will to carry out the

disposition of the deceased’s property. If someone

other than a named Executor is appointed by the

Court, or if a property owner dies without a valid will,

the Court will appoint an Administrator to carry out

the estate’s distribution. When either an Executor

(male), Executrix (female), Administrator (male) or

Administratrix (female) conveys real property of the

estate, the deed used is either an Executor’s Deed or

an Administrator’s Deed. Again, all the technical

requirements of a deed must be met, but, in addition,

the deed typically recites who the deceased person

was, when he/she died, who the Executor or

Administrator confirmed was, the Court that issued

either Letters Testamentary (if a will) or Letters Of

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Acknowledgement

Administration (no valid will), and when issued, and

the file number/docket number of the estate

proceeding. Another usual requirement for a deed

conveyed by an estate is that the full purchase

price/consideration, if any, is spelled out.

5. A Referees Deed. This deed is used when a

Court directs a conveyance of the property, as in the

end game of a mortgage foreclosure proceeding. Like

the deed from an estate, the designation of the Court,

the proceeding, etc., and the full conveyance price are

included in the body of the deed.

6. TITLE SEARCH/TITLE INSURANCE

Any time you acquire property, either real or

personal, there is some risk involved. People deal

with risk in different ways. Some people take extra

precautions. Some people investigate an opportunity

to death. Some people just flat out ignore risks. This

can be very dangerous. Think about it. What is the

major risk you might face in the acquisition of real

property? The answer may be that there is a risk that

you don’t actually get what you bargained for, What

is it that you seek in the acquisition of real property?

The basic answer is: title to the property.

Q.: What is title? A.: Basically it is equated to

ownership (of the property). It is an abstract concept.

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Recording

It does not mean a piece of paper (like the title

certificate for a car). Title does not mean the deed

you receive. You receive title when a properly

executed deed is delivered to you, IF the grantor

executing/signing the deed has title. If the grantor

does not have title, all the grantee receives is a very

fancy piece of paper.

Q.: How do you know if the grantor has title?

A.: Ask!

Q.: Should you take the grantor’s word for it?

A.: Absolutely NOT.

Q.: But the grantor is my father, my brother,

my minister, my friend; should I question their

integrity? A.: NO. But to borrow a line from former

President Ronald Reagan: “Trust, but Verify.”

Q.: How would I verify whether or not the grantor

has title? A.: By having a title search performed. A

title search

basically is a search of the land records in the

jurisdiction where the property is located, to

determine if the person who claims to be the current

owner in fact received a valid deed as grantee in the

past, and then search the same records to see if that

person conveyed the property by deed since its

acquisition. But that is just the beginning. After that

search, you then have to go back to search the records

to see when and by what deed the stated grantor in the

deed wherein your proposed grantor was a grantee got

his or her title. Sound confusing? It is, and can be.

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Title Search

Title Insurance

Q.: How far should a search be made to verify

the chain of ownership of the property? A.: As far

back as the records go, probably to Colonial days!

Q.: What is the chance that you could make a

mistake in verifying the chain of ownership? A.:

Quite likely.

Q.: Isn’t this risky? A.: Absolutely.

Q.: How could or should a person handle this

risk? A.: The answer may be in the method or device

that many people use to deal with risk, in many areas

of their lives. The answer may be: with insurance.

Property acquisition poses some unique risks,

including the risk that you may receive a deed that

does not effectively convey you ownership. The

specialty insurance that deals with this risk is known

as title insurance.

Q.: Where can one obtain this title insurance?

A.: From a title insurance company.

Q.: Is it expensive? A.: It is not cheap. But

consider the alternative. If you acquire a piece of

property without obtaining title insurance, you may

stand to lose your current investment, and any future

appreciation, due to a title defect. There is just no

margin in neglecting to purchase title insurance. In

fact, the issue may be moot, in that if you finance the

acquisition and/or the improvement of the property,

the lender will undoubtedly require you to obtain title

insurance, at a minimum, to protect their interest as

mortgage holder.

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Power of Attorney

A title insurance company is going to assume

the risk of you encountering a title problem after your

acquisition, and issue you a title insurance policy.

This is obtained for a one shot cost, up front, at the

time of the acquisition of the property. It will cover

you for as long as you own the property, and you can

elect a market value rider covering you not only for

your acquisition cost, but for whatever value the

property may increase to in the future.

Before a title insurance company will issue a

policy, it will do a title search to satisfy itself that you

are getting good title. Since they are taking the risk

off of your shoulders onto theirs, it is incumbent on

them to be careful and efficient in their search. The

title insurance companies are regulated by state and

federal law, and required, like any other insurance

companies, to reserve sufficient amounts against

future claims or losses.

Now, I am not an advocate for lining the

pockets of insurance companies with premium dollars,

but, on the other hand, I am not comfortable with the

practice of ignoring risks that may come home to

roost. In fact, virtually no attorney (in his/her right

mind) in the New York metropolitan area will do the

legal work representing a party acquiring real property

if the acquiring party does not purchase title

insurance.

I know that there are other, alternative methods

used to attempt to minimize the risks of title

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Transfer Forms and Taxes

problems, and that, across the country, practices will

vary. I don’t subscribe to any of them. So, if you

want to acquire real property without title insurance,

get someone other than me to assist you. What’s that?

Your Uncle Charlie buys and sells real estate all the

time, and he never wastes his money either on title

insurance or on attorneys? Good luck to Uncle

Charlie! And to you, too, if you follow his lead! (For

Charlie has broken the first piece of advice written in

the Introduction to this book, and you and he are

about to ignore the risks, and break the title insurance

caveat.) See you in Bankruptcy Court, or at the soup

kitchen. We serve chicken noodle on Thursdays, with

a side dish of crow. These two (not so) little side

steps from sanity (using Title Insurance and an

attorney) will eventually bring about your financial

demise. It’s only a matter if time.

7. OTHER DOCUMENTS, FORMS AND COSTS

RELATED TO DEEDS

There are a number of other documents and forms

that typically go hand in hand with transfer of title by

deed. Most of them carry at least some nominal filing

or recording fee/cost; some of them require substantial

payment of taxes and/or fees.

1. Power Of Attorney. As mentioned above in

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Easements

Run With the Land

Section 2, paragraph 1. on execution of deeds, the

situation may present itself that the grantor elects to

have an agent execute (sign) the deed for him or her.

This may come to pass because the grantor knows in

advance that he/she is not going to be present at the

closing/settlement date, and does not want to execute

the deed prior. Sometimes, one member of a

husband/wife team holding property in both names is

not going to be present at closing. In any event, a

grantor can elect to have an agent sign his/her name to

a deed in their stead, either prior to or at a closing.

The obvious problem that arises, is that how does

anyone know if the person signing actually has the

authority to do so? The issue is resolved by the agent

producing an appropriately executed written power of

attorney document, which will be simultaneously

recorded with the deed. The power of attorney is

typically produced with the deed, or, it is possible that

the power of attorney was executed and recorded on

prior occasion. The title search (discussed earlier)

should show a prior recorded power. Whether the

power of attorney was executed and recorded prior, or

produced at closing with the deed, an additional

affidavit by the agent (sometimes called an “attorneyin fact”) that the principal is alive and of full mental

capacity, and that said power is still in full force and

effect at the time of its use, is normally required by

the title company or a cautious grantee.

PROFESSOR’S POINT

On Deeds:

Licenses are Personal

A power of attorney typically must be in writing,

signed by the principal (the one granting the power).

Many (but not all) states require that it be witnessed

by one or more parties and acknowledged (discussed

earlier) in front of a Notary Public/Justice Of The

Peace/Commissioner of Deeds, etc.

Most states have standard statutory forms for

powers of attorney, and the powers may be “general”

in nature, granting wide powers, or “special” in

nature, specifically narrowing the scope of the power.

In addition, a power of attorney may be “durable” in

nature (that is, it may specifically survive the

intervening mental incapacity of the principal.) Most

states’ laws dictate that if a power of attorney is not

“durable” by its terms, it typically will not survive the

intervening incapacity of the principal. In addition, a

power of attorney does not survive the death of the

principal.

2. Transfer Forms and Taxes. In addition to

the deed itself, along with the possible power of

attorney, most states/counties/cities have forms that

must be presented with a deed for recording.

(a) “Stamps”/Deed Tax/Deed Transfer

Tax. Many states impose a transfer/deed tax, and a

form is usually required attesting to the details of the

transfer. This tax is based on the consideration paid

(ex. $2.00 per $500; $4.00 per $1,000; etc.). This is

commonly paid as an expense of the grantor, by local

practice and/or contract provision.

(b) Transfer Tax. Many state or local

jurisdictions impose their own tax on transfers,

typically based on consideration paid. This is over

and above the “Stamps”/Deed Tax/Transfer Tax cited

above, can range often from 1% to 3% of the

consideration and is commonly paid as an expense of

the grantor. Some people refer to it as a “departure

tax.”

(c) Mansion Tax. Some jurisdictions have imposed a

“mansion tax” that is imposed on high priced transfers

(ex. 1% of the consideration in excess of $1Million.). It

varies, but this “tax” is often levied against the

grantee/buyer.

(d) Equalization Forms. Many jurisdictions, usually

counties or states, require another form that cites the

details of the transfer. The governmental body then

inputs this information into its data bank to track the

relation of assessed valuation of property conveyed to

actual market value.

8. OTHER TERMS AND ISSUES

1. Legal Description. As cited above herein, for

a deed to transfer title, it must contain an adequate legal

description. This requirement can be met by utilizing a

number of devices and/or a combination of same.

While a municipal Tax Map Block and Lot might be a

sufficient legal description, a street address alone is

typically deemed insufficient.

(a) Metes and Bounds Description.

This description starts at a Point Of Beginning (POB)

and travels around the property’s boundaries various

metes (distances) and bounds directions/angles).

(b)

Reference to Governmental

Survey System. This description uses latitude and

longitude designations to encompass a property.

(c) Section, Block and Lot. This

description cites a filed map or a “plat map” in the

public records of a County where the land is located,

and identifies parcels by subdivision(s) therein.

2. Covenants and Restrictions. Occasionally,

an owner of property might wish to create certain

conditions or restrictions on future use of property

being conveyed. For example, to insure orderly

development of a property, a developer may put a

number of rules in a subdivision plan, such as:

limitation on square footage of improvements; setback requirements; limitations/prohibitions on other

than residential use; and even the color scheme of the

siding on homes built within the subdivision. These

restrictions would be placed in the deed(s) to the

property, and would bind all future owners thereof,

and it is therefore said that these covenants and

restrictions “run with the land.” Restrictions that are

based on race, color or creed, or that violate other

constitutional protections, have been and would be

declared as void and unenforceable.

3. Easements. An easement is the right to

make use of another person’s land, while a license is a

personal, revocable privilege. An easement benefits

or burdens property, and continues to benefit or

burden future owners of the property (“runs with the

land”). Easements come in various categories (not

discussed here), and are often created by inclusion in

deeds. For example, if a party wanted to convey title

to a piece of property, but wanted to retain the ability

to cross over the conveyed property to allow him

access to the lake, river or forest beyond the property

conveyed, that retained easement would be created by

language in the deed of conveyance. Again, legal

advice should be sought in either retaining an

easement over property conveyed, or acquiring

property that is subject to an easement.