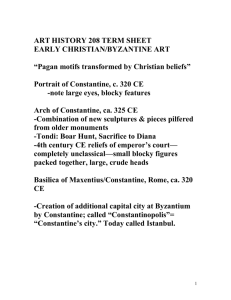

Constantine's Policy of Religious Tolerance

advertisement