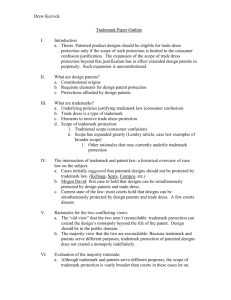

Redefining Likelihood of Confusion in Libman Co. v. Vining Industries

advertisement