A

N E W

Y O R K

L A W

J O U R N A L

S P E C I A L

Litigation

S E C T I O N

www. NYLJ.com

Monday, February 27, 2012

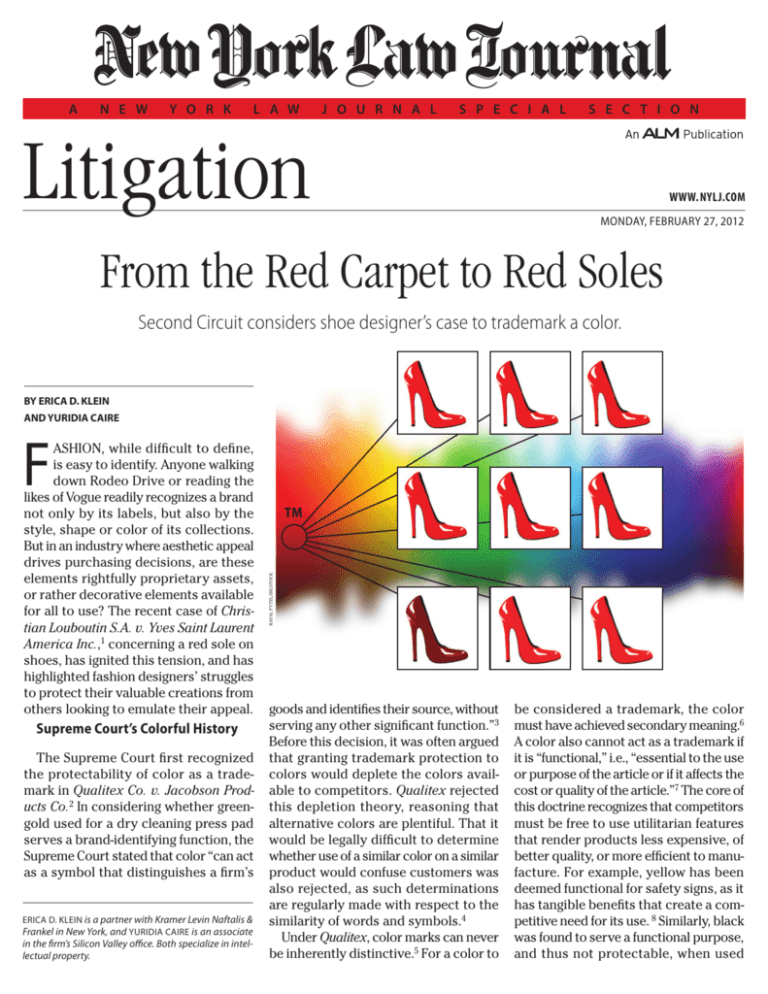

From the Red Carpet to Red Soles

Second Circuit considers shoe designer’s case to trademark a color.

BY Erica D. Klein

And Yuridia Caire

F

Supreme Court’s Colorful History

The Supreme Court first recognized

the protectability of color as a trademark in Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co.2 In considering whether greengold used for a dry cleaning press pad

serves a brand-identifying function, the

Supreme Court stated that color “can act

as a symbol that distinguishes a firm’s

Erica D. Klein is a partner with Kramer Levin Naftalis &

Frankel in New York, and Yuridia Caire is an associate

in the firm’s Silicon Valley office. Both specialize in intellectual property.

TM

RAFAL PYTEL/BIGSTOCK

ASHION, while difficult to define,

is easy to identify. Anyone walking

down Rodeo Drive or reading the

likes of Vogue readily recognizes a brand

not only by its labels, but also by the

style, shape or color of its collections.

But in an industry where aesthetic appeal

drives purchasing decisions, are these

elements rightfully proprietary assets,

or rather decorative elements available

for all to use? The recent case of Christian Louboutin S.A. v. Yves Saint Laurent

America Inc.,1 concerning a red sole on

shoes, has ignited this tension, and has

highlighted fashion designers’ struggles

to protect their valuable creations from

others looking to emulate their appeal.

goods and identifies their source, without

serving any other significant function.”3

Before this decision, it was often argued

that granting trademark protection to

colors would deplete the colors available to competitors. Qualitex rejected

this depletion theory, reasoning that

alternative colors are plentiful. That it

would be legally difficult to determine

whether use of a similar color on a similar

product would confuse customers was

also rejected, as such determinations

are regularly made with respect to the

similarity of words and symbols.4

Under Qualitex, color marks can never

be inherently distinctive.5 For a color to

be considered a trademark, the color

must have achieved secondary meaning.6

A color also cannot act as a trademark if

it is “functional,” i.e., “essential to the use

or purpose of the article or if it affects the

cost or quality of the article.”7 The core of

this doctrine recognizes that competitors

must be free to use utilitarian features

that render products less expensive, of

better quality, or more efficient to manufacture. For example, yellow has been

deemed functional for safety signs, as it

has tangible benefits that create a competitive need for its use. 8 Similarly, black

was found to serve a functional purpose,

and thus not protectable, when used

Monday, February 27, 2012

on outboard boat motors, since black

matches many boat colors and makes

the motor appear smaller.9

The Circuits’ Views

While it is widely agreed that colors

yielding a utilitarian advantage should

not be removed from the market by

granting monopoly status, i.e., a trademark registration, to one player, the case

for refusing a monopoly because a color

is aesthetically appealing is less unanimous. In L.D. Kichler Co. v. Davoil Inc.,10

the Federal Circuit considered whether

the aesthetic appeal of a rust color for

lighting fixtures was functional because

consumers desired lighting fixtures to

be compatible with furnishings. While

the court acknowledged that consumer

preference existed, it held that “[m]ere

taste or preference cannot render a

color—unless it is ‘the best, or at least

one, of a few superior designs’—de jure

functional.”11

The Ninth Circuit’s view of aesthetic

functionality considers whether purely

aesthetic features might be “functional”

because of a perceived competitive need

to copy an ornamental (as distinguished

from utilitarian) product feature.12 As

initially applied, the Ninth Circuit held

a broad view of aesthetic functionality,

favoring consumer interest over trademark rights. For example, in the 1952

decision of Pagliero v. Wallace China

Co., the Ninth Circuit held that because

certain china patterns were desirable

to consumers, they were aesthetically

functional and could be used by competitor hotels.13

The Ninth Circuit more recently narrowed its deference to aesthetic functionality, finding in 2006 that a marquee

license plate bearing the VW company

logo was not a purely aesthetic product feature, but rather served a sourceidentifying function sufficient to support

a claim of trademark infringement.14 The

Ninth Circuit again considered aesthetic

functionality in 2011, in the context of

t-shirts displaying the character Betty

Boop. Initially, the court refused to

enjoin defendant’s sales on the basis

that defendant was using Betty Boop

as a “functional aesthetic component[]

of the product, not trademarks.”15 This

decision prompted numerous amicus

briefs, including by the International

Trademark Association (INTA), the

Motion Picture Association of America,

and several entities representing sports

leagues and universities.

Upon rehearing, the Ninth Circuit withdrew its earlier decision, and issued a

narrowly tailored opinion that avoids

widespread legal and commercial implications.16 Though the fate of the aesthetic

functionality doctrine in the Ninth Circuit

is still uncertain, it appears to be more

limited in its current application than in

its previous history.

To deem a trademark functional

based on aesthetic appeal in the

Second Circuit, a court must find

that the mark is “essential to effective competition.”

Traditionally, the Second Circuit’s view

of aesthetic functionality has been more

restrictive than that of the Ninth Circuit,

requiring “a finding of foreclosure of alternatives” to deny trademark protection.17

To deem a trademark functional based

on aesthetic appeal in the Second Circuit, a court must find that the mark is

“essential to effective competition.”18 The

Christian Louboutin v. Yves Saint Laurent

America case decided by the Southern

District of New York in August 2011, and

now on appeal to the Second Circuit,

questions whether the aesthetic appeal

of color in the fashion industry presents a

special circumstance warranting its own

legal paradigm, or whether the existing

legal framework provides an appropriate

scheme for evaluation.

‘Louboutin v. YSL’

Louboutin sued YSL for trademark

infringement and sought a preliminary

injunction to enjoin YSL from marketing

any shoes that use the same or confusingly similar shade of red as Louboutin’s

protected “Red Sole Mark.” The “Red

Sole Mark” is the subject of a federal

registration conferring protection of

“a lacquered red sole on footwear” for

use in connection with “women’s high

fashion designer footwear.”19 The YSL

shoes at issue comprised a monochromatic red body and red sole. As framed

by the court, “[t]he narrow question

presented here is whether the Lanham

Act extends protection to a trademark

composed of a single color used as an

expressive and defining quality of an

article of wear produced in the fashion

industry.”20

Louboutin’s registration gives rise

to a statutory presumption of validity. 21 The court acknowledged that

the Lanham Act has been applied in

the fashion industry to “distinct patterns or combinations of shades that

manifest a conscious effort to design

a uniquely identifiable mark embedded in the goods.”22 Yet, because the

court analyzed Louboutin’s position as

a claim “to the color red” rather than

the more limited color and placement

stated in the registration, Louboutin’s claim was found “overly broad

and inconsistent with the scheme of

trademark registration established by

the Lanham Act.”23

Accordingly, the aesthetic appeal

of Louboutin’s shoes was found to be

functional, and Louboutin’s preliminary

injunction motion was denied.24 The

court posited that fashion should not be

viewed within the district’s precedential

framework, but rather should be subject

to a different analysis. “Because in the

fashion industry color serves ornamental and aesthetic functions vital to the

robust competition,” the court found

that Louboutin is unlikely to be able to

prove that its Red Sole Mark is entitled

to trademark protection, and infringed

by YSL.25

The Louboutin decision garnered

much attention within the fashion

industry and the Trademark Bar. An

amicus brief filed by Tiffany & Co.

argued that the Louboutin case adopted

a “sweeping and unprecedented per se

Monday, February 27, 2012

rule against granting trademark protection to any single color that is used on

any ‘fashion item,’ even where the color has achieved ‘secondary meaning’

and is associated with a single brand”

(emphasis in original).26

Similarly, INTA argued in its amicus

brief that the district court misconstrued

Louboutin’s mark as consisting of “the

color red” as opposed to a “lacquered

red sole on footwear” as stated in the

registration, and did not properly consider the validity of the registration.27

INTA further argued that the district

court erred in applying the Ninth Circuit’s

aesthetic functionality test rather than

the aesthetic functionality test of the Second Circuit.28 On the YSL side, a group

of university professors filed an amicus

brief arguing that the district court properly applied the doctrine of aesthetic

functionality, and that color marks are

inherently suspect.29 Oral argument was

held in front of the Second Circuit on

Jan. 24, 2012.

For the time being, while fashion brand

owners may successfully secure registrations for color trademarks, enforcing

such registrations appears less certain.

Thus, with trademark rights and remedies

in flux, it is important to consider other

forms of protection available to the fashion world.

Copyright and Patent Law

In addition to trademarks, certain

elements of fashion may find protection through copyright or patent law.

Copyright law protects works “fixed

in any tangible medium” belonging to

a wide range of creative or artistic works,

including “pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works.”30 Certain fashion articles

have been held protectable on this basis,

including David Yurman jewelry designs31

and Diane von Furstenberg prints.32 However, pursuant to the “useful articles” doctrine, copyright protection is available

only if there is expressive component

“separable from its useful function.”33

As such, most clothing and shoes are

unlikely to satisfy this test due to the

function performed for the wearer.

Patent law also provides limited protection for elements of fashion design. In

general terms, a “utility patent” protects

for 20 years the way an article is used and

works (35 U.S.C. §101), while a “design

patent” protects for 14 years the way an

article looks (35 U.S.C. §171).34 Design

patents have been secured by industry

leaders such as Levi for jeans,35 Gucci

for handbags36 and Stuart Weitzman for

shoes.37 Both types of patents may be

obtained on an article if invention resides

in its utility and ornamental appearance,38

such as Crocs shoes.39 It may take up

to 18 months to obtain either type of

patent, however, and the process may

incur thousands of dollars. Thus, because

copyright and patent laws provide only

limited intellectual property protection

and do not always correspond with the

lifespan of fashion articles or fashion

trends, alternative options for legal protection have long been sought.

Pending Legislation

The Innovative Design Protection and

Piracy Prevention Act (S.3278) (IDPPA)

was introduced in August 2011, sponsored by Sen. Charles Schumer, D-N.Y.

The IDPPA follows a series of earlier

bills that sought to increase the scope

of copyright protection available to

fashion designs. If enacted, the IDPPA

would amend the Copyright Act to provide three years of protection to fashion

designs that meet defined standards of

originality and novelty. As defined in the

bill, a fashion design is the “appearance

as a whole of an article of apparel including its ornamentation,”40 and infringement of a protected design occurs if a

copy is found to be “substantially identical in overall visual appearance”41 to

the protected design, so long as it can

be “reasonably inferred [that the copyist] saw or otherwise had knowledge

of the protected design.”42 Advocates

and adversaries are divided regarding

whether creativity would be stifled by

more protection or whether the lack of

protection hinders innovation. There is

a strong case to be made on either side.

But for now, as with the protection of

color in the nation’s fashion capital, we

must wait to see what the next season

brings.

••••••••••••••••

•••••••••••••

1. 778 F. Supp. 2d 445 (S.D.N.Y. 2011).

2. 514 U.S. 159 (1995).

3. Id. at 166.

4. Id. at 167.

5. Id. at 159; see also Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure (TMEP) (8th ed. Oct. 2011) §1202.05(a).

6. TMEP §1202.05(a).

7. Qualitex, 514 U.S. at 165.

8. In re Orange Communications Inc., 41 U.S.P.Q.2d (BNA)

1036 (T.T.A.B. 1996) (color yellow held to be functional for

public telephones and telephone booths because it was more

visible under all lighting conditions in the event of an emergency).

9. See Brunswick Corp. v. British Seagull Ltd., 35 F.3d 1527

(Fed. Cir. 1994), cert. denied, 514 U.S. 1050 (1995), overruled

in part on other grounds by Cold War Museum v. Cold War Air

Museum, 586 F.3d 1352 (Fed. Cir. 2009).

10. 192 F.3d 1349 (Fed. Cir. 1999).

11. Id. at 1353.

12. See Pagliero v. Wallace China Co., 198 F.2d 339 (9th Cir.

1952); see also Au-Tomotive Gold Inc. v. Volkswagen of America

Inc. et al., 457 F.3d 1062, 1071 (9th Cir. 2006).

13. Pagliero, 198 F.2d 339.

14. Au-Tomotive Gold Inc., 457 F.3d at 1075.

15. Fleischer Studios Inc. v. A.V.E.L.A. Inc., 636 F.3d 1115,

1124 (9th Cir. Feb. 23, 2011).

16. Fleischer Studios Inc. v. A.V.E.L.A. Inc., 654 F.3d 958 (9th

Cir. Aug. 19, 2011).

17. Wallace Int’l Silversmiths Inc. v. Godinger Silver Art Co.,

916 F.2d 76, 81 (2d Cir. 1990).

18. Landscape Forms Inc. v. Columbia Cascade Co., 70 F.3d

251, 253 (2d Cir. 1995).

19. U.S. Registration No. 3,361,597 issued Jan. 1, 2008.

20. Christian Louboutin v. Yves Saint Laurent America, 778 F.

Supp. 2d 445, 451 (S.D.N.Y. 2011).

21. Id. at 450.

22. Id. at 451.

23. Id. at 454.

24. Id. at 458.

25. Id. at 449.

26. Brief of Amicus Curiae Tiffany (NJ) LLC and Tiffany &

Co. in Support of Appellants’ Appeal Seeking Reversal of the

District Court’s Decision Denying Appellants’ Motion for Preliminary Injunction at 3, Christian Louboutin S.A., 778 F. Supp.

2d 445.

27. Brief of Amicus Curiae International Trademark Association in Support of Vacatur and Remand at 1-2, Christian

Louboutin S.A., 778 F. Supp. 2d 445.

28. Id. at 2, 24.

29. Brief of Amicus Curiae Law Professors in Support of Defendants-Counter-Claimants-Appellees and Urging Affirmance

at 11, Christian Louboutin S.A., 778 F. Supp. 2d 445.

30. 17 U.S.C. §102.

31. See, e.g., U.S. Copyright Registration No. VA0001702208.

32. See, e.g., U.S. Copyright Registration Nos. VA0001637221,

VAu001025526.

33. See, e.g., Chosun Int’l. Inc., v. Chrisha Creations, Ltd., 413

F.3d 324 (2d Cir. 2005) (holding that costume designs may warrant copyright protection); Kieselstein-Cord v. Accessories by

Pearl Inc., 632 F.2d 989 (2d Cir. 1980) (finding belt buckle designs copyrightable).

34. MPEP §1502.01.

35. See, e.g., U.S. Patent D436,714.

36. See, e.g., U.S. Patent D564,224.

37. See, e.g., U.S. Patent D545,039; D629,595.

38. MPEP §1502.01.

39. Crocs hold one patent covering various utility aspects

of its footwear, U.S. Patent No. 6,993,858 B2 and three design

patents, U.S. Patent Nos. D517,788, D517,789 and D517,790.

40. IDPPA, H.R. 2511, 112th Cong. §2(a)(7)(A).

41. Id. at §2(e)(3)(A).

42. Id. at §2(e)(1)(C).

Reprinted with permission from the February 27, 2012 edition of the NEW YORK

LAW JOURNAL © 2012 ALM Media Properties, LLC. All rights reserved.

Further duplication without permission is prohibited. For information, contact 877257-3382 or reprints@alm.com. # 070-02-12-34