Negative Inversion and Degree Inversion in the English DP

advertisement

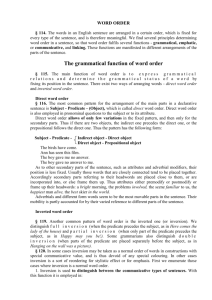

Negative Inversion and Degree Inversion in the English DP Erika Troseth CUNY Graduate Center etroseth@gc.cuny.edu 1. Introduction That parallels hold between the sentential and nominal domains has been a fairly mainstream idea at least since Abney (1987). Taking a careful look at some fairly simple inversion data from English further supports this previously hypothesized parallel, and in addition allows for some surprising and new insights. In particular, exploration of sentences (1) – (8) provides evidence for a DP-internal NegP and makes clear the distinction between negative inversion and degree inversion inside the DP. One of the most important benefits of the approach presented here is that negative inversion is licensed locally and is not countercyclic. Unlike many approaches to DPs of the type discussed here, I propose that the adjective in (6-8) is predicative rather than attributive. For much of the analysis presented here, the predicative vs. attributive distinction is not crucial, but the long-noticed requirement that a singular indefinite article be present and the long-noticed fact that of is optional in DPs of the type in (6) and (8) can be tied to predicate inversion—a proposal that clearly requires predicative rather than attributive adjectives. (1) Attila is a good athlete (3) Attila is a very good athlete (5) *Attila is very good (of) an athlete (7) Attila is not very good (of) an athlete (2) *Attila is good an athlete (4) *Attila is a too good athlete (6) Attila is too good (of) an athlete (8) Attila is not too good (of) an athlete Examples (1) and (2) illustrate that in a simple DP in English, the order article-adjective-noun is grammatical, while the order adjective-article-noun is not. Example (3) illustrates that certain intensifiers, here very, may legitimately be positioned between the article and the adjective. Other such intensifiers include particularly. Example (4) shows that some intensifiers (here, too) may not be positioned between the article and the adjective. Too is among the set of intensifiers described here as degree words. These words will be characterized in 5.3; they are the same words argued in Corver (1997) to occupy Deg0. Example (4) is ungrammatical because the degree word follows the article. Example (5) shows that in a positive sentence, when an intensifier of the very type precedes an adjective, the intensifier+adjective may not precede the article. Example (5) is ungrammatical because very-type intensifiers are not licensed to raise, and so the movement of very good leftward is not allowed. Example (6) shows that when the intensifier that precedes the adjective is a degree word, the degree word and adjective may precede the article. In fact, comparing (6) with (4) shows that the degree word+adjective must precede the article. Taken together, examples (3) - (6) show that while certain intensifiers, those of the very variety, cannot be positioned to the left of the article, other intensifiers, the degree words, must be positioned to the left of the article. Example (7) shows that the very-type intensifiers, which ordinarily cannot precede the article, may do so in contexts of negation. Example (8) simply shows that the requirements we see on word order inside the English DP with respect to degree words go unchanged in contexts of negation. The raising of a degree word in combination with the pied-piping of the adjective will here be called degree inversion, and the raising of material licensed by negation will here be called negative inversion. Sections 2, 3, and 4 provide some background with respect to the way in which adjectives will be treated in both degree inversion and negative inversion. Section 3 motivates a predicational approach, and section 4 covers the basics of predicate inversion. Section 5 is devoted to degree inversion. Section 6 focuses on the optional of and the required indefinite article (which receives further attention in section 7). Negative inversion is covered in section 8, and section 9 investigates in more detail the behavior of the abstract negation introduced in section 8. Parallels with the clausal domain, as well as topics for further exploration are found in sections 10, 11, and 12, before the conclusion in section 13. 1 2. The adjective can be pied-piped The contrast between (4) and (6) provides evidence for DP-internal movement of a constituent that contains the adjective even in contexts in which negation is not present at all (not in IP, not in DP). (4) *Attila is a too good athlete (6) Attila is too good (of) an athlete (9) DP a too good XP athlete The schematic derivation above illustrates that DP-internal movement does occur. The structure in (9) should not be taken too seriously, because it will turn out that there is never a stage in the derivation for degree-inverted DPs that can be represented exactly as in (9). Given the contrast between (4) and (6), it appears that movement of the type shown in (9) must occur when degree words combine with the adjective. However, this approach cannot be directly carried over to account for examples such as (7). That is, it is not possible to simply substitute very for too in (9). To do so would be to predict that example (5) is good. Example (5), which does not include negation, does not allow leftward movement of very good, while example (7), which does include negation, permits leftward movement of very good. The contrast between sentences like He is not a very good student and He is not very good of a student will be discussed briefly in section 8.2. We can begin to understand the contrast between (5) and (7) and avoid extension-condition violations by base-generating a negative element on the DP-internal predicate. Before addressing this subject, which is perhaps the most interesting and fruitful aspect of this paper, it is essential to look at degree inversion in detail, since many of the mechanisms and assumptions set out in that discussion will inform the treatment of negative inversion. 3. Predicative, not attributive adjectives Previous analyses have taken the adjectives in DP-internal degree inversion (Matushansky, 2002; Kennedy and Merchant, 2000) and negative inversion (Borroff, 2000) contexts to be attributive. However, adjectives that allow different interpretations depending on whether they appear in prenominal position or post-copula position illustrate that these adjectives are in fact predicative. In (10), with the adjective poor in prenominal position, poor can be interpreted in two ways. Bill Bradley can be someone to pity, or he can be someone who doesn’t have much money. In (11), with the adjective poor in post-copula position, the only available interpretation is that Bill Bradley doesn’t have much money. The “pitiable” reading of poor is absent. In short, the attributive use of poor is ambiguous, while the predicative use of poor is not. (10) Poor Bill Bradley didn’t make it through the primary elections of 2000. poor = feel sorry for or has little money (11) Bill Bradley is poor. poor = has no money Example (12) shows the adjective poor in a degree-inverted DP. Only the predicative interpretation of poor is available.1 (12) Bill Bradley is too poor of a man... poor = has no money 1 It may also be the case that the degree word too is solely responsible for the loss of the “pitiable” reading. 2 The predicative interpretation of adjectives in inversion contexts provides evidence that they originate not as attributive modifiers but as predicates, and are thus able to participate in predicate inversion. The basics of predicate inversion will be covered in the next section, before they are applied to degree inversion and negative inversion. 4. Predicate inversion Predicate inversion, which can occur in the clause (Moro, 1997) and in the DP (Bennis, Corver, Den Dikken, 1998), is an operation essential to the discussion of the DPs discussed here. In predicate inversion, the predicate and its argument (or subject) are here depicted as originating in a small clause. The head of the small clause raises to the head of the clause above it, a domain-extending head movement that licenses raising of the predicate to an A-position it would otherwise be “ too far” from. This is illustrated in (13). (13) FP F’ F SC SUBJECT HEAD PREDICATE Looking at an example like (14), with the corresponding derivation in (15), makes this a bit more concrete. (14) I think that the best philosophy is sink or swim. (15) FP F’ F SC sink or swim HEAD the best philosophy This is the basic approach I will be taking to degree inversion and negative inversion inside the English DP. Predicate inversion (a variety of A-movement), licensed by domain-extending head movement, will be the first step in both cases. In the degree inversion cases and the negative inversion cases, the subsequent movement will be a case of A-bar movement. This second step will be similar, but because there are interesting differences, degree inversion and negative inversion will be discussed in separate sections. Degree inversion I turn to next. 3 5. Degree inversion Examples (3) - (6), repeated below, show that although very and too can be generally understood as intensifiers, when they combine with an adjective, their behavior within the DP is different. Very good may not precede the article, while too good must. (3) Attila is a very good athlete (4) *Attila is a too good athlete (5) *Attila is very good (of) an athlete (6) Attila is too good (of) an athlete Separating intensifiers like very from those like too, and extending the proposal of Hendrick (1990), allows for an account of the contrast between these examples. It turns out that too belongs to a small set of words classified by Corver (1997) as degree words, while very does not. 5.1 Hendrick 1990 Hendrick argues for NP-internal A-bar movement in part on the basis of examples like the two below. (16) *A how tall man did Jane see? (17) [How tall]i a ti man did Jane see? Hendrick’ s (4) Hendrick’ s (2) Hendrick’ s proposal is directly relevant to the discussion of degree inversion, as example (6) can now be treated as a straightforward instance of degree inversion, if how and too can be shown to exhibit the same behaviors. Note that Hendrick treats the constituent how tall as an attributive modifier of the noun man, while I treat this constituent as predicative, as discussed in section 3. The component of Hendrick’ s analysis that I do adopt is that there is A-bar movement of this predicate to the left edge of the DP. Recall that predicate inversion is A-movement. Thus, for me, the predicate undergoes A-movement and then A-bar movement, while for Hendrick only the latter of these two steps occurs. In section 6, I will show that the presence of the indefinite article is a product of A-movement (predicate inversion); the second step (an A-bar movement) will be discussed in more detail in section 5.3. This second movement is to the specifier of a phrase that may optionally be headed by of. A small family of words, including too, behaves just as how does in Hendrick’ s examples. The degree feature of how is described in section 5.2, before extending the proposal to the small set of degree words. 5.2 DP-internal raising of how Degree words (those that possess a degree feature) will here be taken to be those pre-adjectival modifiers that pattern as how does below. They require the fronting of the modifier+adjective to the left edge of the DP. That how does indeed have a degree feature, separate from its wh-feature, can be seen in the examples below. (18) *Jane saw a HOW TALL man? (20) Jane saw HOW TALL a man? (19) *A how tall man did Jane see? (21) How tall a man did Jane see? Examples (18) and (19) are both ungrammatical. Whether the wh-DP has raised to the left periphery or remains low, the sentences fail because the degree feature on how has not been checked within the DP. Examples (20) and (21) are both grammatical. Whether the wh-DP has raised to the left periphery or not, the examples are fine because within the DP, how has raised leftward, pied-piping the adjective. Whatever other features how may contribute, it, like too, contributes a feature that requires DP-internal A-bar movement. This feature here will simply be called a degree feature. 5.3 Degree words The degree word how was used above to illustrate the behavior of degree words, but there is a small family of words that pattern as how does above—requiring the fronting of the modifier+adjective to the edge of the DP. These are 4 the words that correspond to Deg0 in Corver (1997): too, how, as, that, so.2 The examples below show that the degree feature introduced by these words must be checked in overt syntax. Examples in which the degree word+adjective remains low are ungrammatical; examples in which the degree word+adjective has raised are grammatical. In all cases, in raising to check the degree feature, the adjective is pied-piped leftward. Example (22), with too serious raised leftward, is grammatical as the degree feature has been checked. Example (23), with too serious lower in the DP, is not grammatical because the degree feature has not been checked. The same pattern is shown for the other degree words in (24) – (29). (22) The Seventh Seal is too serious (of) a movie. (23) *The Seventh Seal is a too serious movie. (24) Green is as becoming (of) a color. (25) *Green is an as becoming color. (26) Willie Nelson is that talented (of) a songwriter. (27) *Willie Nelson is a that talented songwriter. (28) Holding all 50 states’ primary elections on the same day is as reasonable (of) a proposal. (29)*Holding all 50 states’ primary elections on the same day is an as reasonable proposal. The reason for the contrast between the sets of pairs above is perhaps seen more clearly in the derivation represented in (30). Degree words possess a degree feature [deg] that must be eliminated in overt syntax. When this feature is present, it is located in D; elimination of [deg] is accomplished by raising a phrase with this feature to SpecDP. This is illustrated in (30). The movements associated with predicate inversion, which will be discussed in section 6, are also depicted. (30) DP too longz D’ >GHJ] of NumP [deg] tz’ 1XP a SC SUBJECT tz With the contrast between the pairs above explained and the basic mechanics of predicate inversion covered, the next section focuses on the elements of and a. Of shows up in these structures optionally, while a is required. Adopting a predicate inversion approach allows for a fairly clear account of the presence of the indefinite article when degree inversion or negative inversion have occurred inside the DP and for the fact that of and a occupy distinct heads within the DP. 2 Exclamatives may be analyzed in a similar but not identical way. How big (of) a house does not allow the plural *How big (of) houses while the exclamative allows singular, plural and mass Ns What a volcano!, What volcanoes!, What lava! 5 6. of and a That of is optional in degree inversion contexts has been noted in Bresnan (1973) and Abney (1987) among others. In Bennis, Corver, and Den Dikken’ s (1998) account of the Dutch and English N of a N construction, they propose an analysis in which of/van and a/een occupy the same head (a adjoins to of). While they do not discuss degree inversion or negative inversion, their analysis of of and a cannot be carried directly over to the degree inversion and negative inversion cases. Below is the Bennis et al. derivation of een beer van een vent/a bear of a man. (31) DP D FP beerj F’ F Xi+van XP vent X’ ti tj In (31) vent/man originates as the subject of the XP (possibly a small clause), and beer/bear originates as the predicate. For predicate inversion to be licensed (for beer/bear to raise to [Spec, FP]), domain-extending head movement must occur. X0 (which Bennis et al. describe as host to the “ spurious article” een and other “ linkers” ) must raise to F0. Carrying this proposal over to degree inversion would result in derivations like the one below (here for too long (of) a letter). (32) FP too longj F Xi=a + of F’ XP letter X’ ti tj Setting aside word-order problems inside the complex F head—that is, that although the desired word order is of a, the word order we see in (32) is a of—the important thing to note is that (of)-a has been derived through a headadjunction operation. If (of)-a is indeed a complex head, it should resist being separated, as excorporation should result in ungrammaticality. The extraction facts illustrated in examples (33) and (34) show that of and a must in fact not be occupying the same head. (33) ??A letter he wrote too long of, and a book, he wrote too short of (34) *Of a letter he wrote too long, and of a book, he wrote too short If of and a occupied the same head, (33) should be strictly underivable. That (33) is actually better than (34) points to the conclusion that of and a occupy distinct heads. Thus, the Bennis et al. account of the N of a N construction cannot be directly carried over to an account of the examples discussed here. Looking at cases in which of is present, the derivation below provides a and of with separate head positions. 6 (35) DP too longz D’ >GHJ] of NumP [deg] tz’ 1XP a SC SUBJECT tz In (35), predicate inversion does not result in an of, but an a. The presence of the indefinite article is a result of predicate inversion, an instance of A-movement. The predicate headed by the degree word must then raise to check its degree feature, an instance of A-bar movement. The D-head may be lexically filled in one of two ways. Of may optionally be inserted in D, or a may raise from the head of NumP to D. To derive (34) would require raising of D-bar in (35), an entirely illegitimate step. Raising NumP, producing (33), results in a subjacency violation, as SpecDP is not an available intermediate landing site. Providing of and a with separate head positions is also an approach taken in Kennedy and Merchant (2000), although for entirely different reasons. 7. More on a: The indefinite article constraint It has been noted that in English constructions of this type disallow plural and mass nouns. This constraint is not likely a semantic constraint, as Danish, for example, allows singular, plural and mass nouns in the same construction. (36) så stort et hus so big a house ‘so big a house’ (37) Han opdraetter lige så fine får som sin he raises (just) as fine sheep as SELF' s ‘He raises sheep just as fine as his father’ (Danish and Norwegian, Delsing 1993:138) far father (38) Gæssene lavede så stort et spetakel at vi ikke kunne sove geese-DEF made so big a noise that we not could sleep ‘The geese made so much noise that we could not sleep.’ (Danish, Line Mikkelsen, p.c.) (Danish, Line Mikkelsen, p.c.) If these constructions are derived in English through predicate inversion, as has been argued above, then there is a syntactic, not a semantic, reason for the presence of the indefinite article. Recall that predicate inversion requires that the head of the small clause raise (that is, domain-extending head movement is required). Following Bennis et al. I suggest that the head of the small clause hosts a spurious article a, and that a’ s feature specification is [-PLURAL]. The presence of the spurious indefinite article (a consequence of the syntax of these DPs) is then what precludes plural nouns. Mass nouns seem trickier, as examples like (39) are ungrammatical. (39) *She always puts too hot (of) water in my teacup. However, mass nouns are not inherently plural, and so should be able to withstand the presence of the spurious indefinite article. Indeed they can. Mass nouns will be interpreted as count nouns. Example (40) is either interpreted as too strong a cup of coffee (French press) or too strong a type of coffee (dark roast). (40) She ordered too strong (of) a coffee 7 With degree inversion covered, including an analysis of the optional element of and the required presence of the indefinite article, we can turn to negative inversion. 8. Negative inversion is licensed locally Many of the details of negative inversion are the same as for degree inversion, but the approach to negative inversion proposed here offers some novel ways of looking at things that turn out to be more successful than previous approaches to negative inversion. The approach presented here allows for negative inversion to occur in a way that does not violate the extension condition. A key component of this analysis is that negation can, and indeed sometimes must, be base-generated within the DP. 8.1 Merging NEG in IP leads to countercyclicity Exploring examples (5) and (7), repeated below, illustrates that if DP-internal negative inversion depends on a negative element that is merged in IP, the derivation will be countercyclic. Example (7) illustrates an instance of negative inversion. The leftward movement of very good is licensed by the presence of negation, which can be seen by comparing (7) with (5). Example (5), in which no negation is present, is ungrammatical. One question we should ask is where exactly the negation originates. To arrive at a derivation that is not countercyclic, it turns out that it is in fact necessary that the negation originate inside the DP. If not in (7) originated in IP (as depicted in (41)), the DP would be completely built prior to merger of not. Inversion would then have to be performed after the completion of the DP, and SpecDP would be projected in overt syntax after the introduction of the Neg head. Thus, raising of very good to SpecDP would be radically countercyclic. (5) *Attila is very good (of) an athlete (7) Attila is not very good (of) an athlete (41) IP NegP not DP a Ç XP very good È athlete A second possible scenario would involve raising of very good prior to merger of not. This is shown in (42). (42) IP NegP not DP È a Ç XP very good athlete 8 Raising of very good to SpecDP would not be countercylic, but it would not be licensed. Looking again at example (5) shows that very good cannot raise without the trigger of a negative element. If the first step depicted in (42) were legitimate— i.e., if very good could raise on its own— this would fail to capture the fact that in (5) raising leads to an ungrammatical sentence. The failure of a negation merged in IP to license DP-internal negative inversion opens the door to exploration of the possibility that it is a negation merged inside the DP that licenses the inversion. 8.2 NEG in DP Merging negation in DP, rather than in IP, provides a superior account of the facts. Before turning to actual examples, it will be helpful to be familiar with a couple of key elements from the analysis of negative polarity items described in Postal (2000). Although DP-internal NPIs are not discussed here, some tools from Postal’ s approach to these items will be essential. The analysis in Postal (2000) leads to the conclusion that NPI any may take at least two forms3 underlyingly: “ small” any, in (43), which permits exceptives, as in (44), and “ large” any, in (45), which does not, as in (46). (43) [NEG [some]] = any (45) [NEG [NEG [some]]] = any (44) No jurors believed any witness (but Attila) (46) Precisely two jurors believed any witness (*but Attila) In both the large and small structures that underlie NPI any, the surface form any results from movement of NEG(s) away from the structure(s) in (43) and (45). That is, the abstract NEG is able to run away from its merge site and eventually be deleted or be lexicalized. The essential ingredients from Postal that I wish to capitalize on are the base-generation of negative elements within the DP and the fact that these elements are capable of raising out into the clause. With these tools in hand, we can now take a new look at example (7). Following this analysis, the derivation of (7) runs schematically as in (47). Taking the first ingredient from Postal— the DP-internal merging of NEG— the predicate not very good can be merged inside of the DP. Negation heads this predicate (this will be discussed later in this section) and forces raising within the DP. The second ingredient from Postal is that negation is free to leave its host. This is not apparent in example (7), but discussion of examples (17a) and (18a) below will show that negation may indeed leave the predicate that it heads. (47) illustrates that the target of the predicate in negative inversion is SpecDP, just as in the degree inversion cases. (7) Attila is not very good (of) an athlete (47) DP a not very good XP athlete By base-generative negation inside the DP and permitting it to leave its host after negative inversion has occurred leads to two benefits.4 The optionality of negative inversion can, in examples of this type, be eliminated. More 3 There may at present be four underlying forms of any, Paul Postal, p.c. In this paper I will consider only the two discussed in Postal (2000). 4 There is possibly a third benefit if we look at the interpretation of negative inverted DPs and DPs that are not inverted yet are in the scope of negation. Borroff notes that the examples (i) and (ii) can be interpreted in different ways. (i) (ii) John is not [DP a very good student] John is not [FP very good a student] 9 importantly, negative inversion does not violate the extension condition (Chomsky (1995)). If (7) were analyzed with NEG originating in IP, inversion would be triggered after completion of DP, violating the extension condition. Taking the approach in (47), however, the derivation is fully cyclical. This approach also permits a straightforward explanation of the contrast between the slightly more complex examples in (48a) and (49a). The details of predicate inversion covered in section 4 will be essential to the analysis. (48a) I do notj think that [sink or swim] is [tj very good (of) a philosophy]5 (49a) *I do notj think that [tj very good (of) a philosophy]i is [sink or swim] ti (48b) IP (49b) NegP notj 93 NegP notj 93 think &3 that IP think &3 IP sink or swimz that I is IP [tj very good (of) a philosophy] z SC tz I is [tj very good (of) a philosophy] sink or swim SC tz Treating not very good (of) a philosophy as the predicate of sink or swim and assuming predication relationships are established in a small clause, predicate inversion has taken place in (49) but not in (48). If the licensing of negative inversion were simply a matter of appearing within the c-command domain of a downward entailing element (here not), there should be no contrast between (48) and (49). If anything, (49) should be better as the inverted DP is, at least in terms of linear order, closer to not. In (49), predicate inversion has placed not very good (of) a philosophy in a left-branch position. The negation is in the left branch of this left branch, and predictably is trapped— (49) is out. Merging NEG in IP was ruled out above for examples of this type because the DP-internal raising of very good would go entirely unexplained. (48) and (49) provide further evidence for merging NEG inside the DP, because an account in which NEG is merged directly in IP could not account for the contrast between them. The two interpretations that are possible, looking at (i) and (ii) are below. One she calls “ sentential negation,” the other “ constituent negation.” Sentential negation: What John is not, is a very good student. Constituent negation: What John is, is a not very good student. In the case of sentential negation, it could be the case that John is any sort of student except for a very good one. He could exceed this mark (perhaps he is an excellent student) or fall short of this mark (perhaps he is just good, or even bad). In the case of constituent negation, the only interpretation available is that John is a not very good student (a bad student). The example in (i), without negative inversion, can be interpreted as constituent negation or sentential negation. The example in (ii), with negative inversion, can only be interpreted as an instance of constituent negation. For Borroff, negation never originates inside the DP, but on the account proposed here, it does. The fact that (ii) is restricted in that it may only be interpreted as a case of constituent negation makes sense because NEG is indeed basegenerated on the predicate and negates a constituent. 5 Think is traditionally a neg-raising verb, but this example works also with the verb know, which is not a neg-raising verb. If the base-generation of NEG down low and subsequent raising into the clause is indeed a viable option, then there is the question of which verbs are neg-blockers (as opposed to neg-raisers). This question I leave open here, but clearly it is necessary at some point to account for this. Postal (2000) is also not explicit about how to handle this question. 10 Example (49) also provides insight about the structure of the small clause predicate, namely that NEG is its head. That is, the structure of not very good within the complex DP is as in (50), not as in (51). (50) NegP (51) NEG XP very AP XP AP YP good NEG A’ X’ very good If the structure were as depicted in (51), it would be impossible for the negation to leave the predicate and travel up into the clause. In (48) the negation does indeed leave the predicate and travel up to IP. Thus, the predicate not very good must be headed by negation. This DP-internal NegP is as in (50). 9. The path travelled by NEG For the negative inversion cases described above, it has been shown that there are advantages to merging negation within the DP and allowing it to raise out. In fact, this approach has been shown to be necessary in examples of this type. A reasonable question to ask is what is the nature of the path NEG travels. Probing examples (48) and (49) further shows that NEG may and must travel through both of the IP domains, unless it lexicalizes in the lower IP. NEG’ s path ends just in case it is lexicalized. That NEG may travel through both IPs and may be lexicalized in either of the IPs can be seen in (48a) (repeated below) and (48c). Both examples are grammatical, (48a), with NEG lexicalized in the higher IP, and (48c), with NEG lexicalized in the lower IP. A schematic derivation for (48a) and (48c) is shown in (52), with (48a) corresponding to the high lexicalization of NEG and (48c) corresponding to the low lexicalization of NEG. (48a) I do notj think that [sink or swim] is [tj very good (of) a philosophy] (48c) I think that sink or swim is notj [tj very good (of) a philosophy] (52) IP I’ 93 notj think &3 that IP sink or swimz notj I’ is SC tz [tj very good (of) a philosophy] Examples (48a) and (48c) and the schematic derivation in (52) illustrate that NEG may travel through any IP. Whether “ stopping over” in all IPs on NEG’ s way up is actually required is not yet apparent. That NEG must necessarily travel through all IP regions can be seen by looking more closely at (49a), repeated below. (49a) *I do notj think that [tj very good (of) a philosophy]i is [sink or swim] ti As described earlier, this sentence is out on a derivation in which NEG leaves the DP after predicate inversion has occurred, because it is trapped in the left branch of a left branch. This derivation is depicted in (49b), repeated 11 below. However, there is another possible derivation for (49a), and this derivation must also be ruled out. A portion of this derivation is shown in (49c). (49b) IP (49c) NegP notj IP [tj very good (of) a philosophy] z 93 I think &3 that I’ NegP notj IP 6& sink or swim tz [tj very good (of) a philosophy] z I is SC sink or swim tz In (49c), NEG has first raised out of the small clause predicate. After NEG has left, predicate inversion occurs, with the predicate crossing the negation. This derivation is not allowed, no matter whether NEG stays down low or eventually raises to the higher IP. That is, (49a) is out as is (49d), with NEG lexicalized in the lower IP. (49d) *I think that [tj very good (of) a philosophy]i is notj [sink or swim] ti Predicate inversion is generally blocked by an intervening negative element. A simpler example of failed predicate inversion, shown in (53), further illustrates this point. (53) *In this tower never wept Rapunzel.6 If in (49c) NEG could leave the DP while the DP is still in the small clause (as is the case in (48a) and (48c)) and skip the lower IP altogether, there would exist a derivation for (49a) under which it would be acceptable. This, however, is not the case. Thus, the minimal conclusion with respect to movement of NEG is that it must touch down in all IPs “ on its way up,” and that it exhibits flexibility with respect to where it actually lexicalizes. 10. The landing site of predicates Above, the landing site of predicates in negative inversion and degree inversion was argued to be SpecDP. My proposal is similar to that in Borroff (2000) in that negative inversion and degree inversion target the same landing site. My proposal differs from that of Borroff (with respect to negative inversion and degree inversion) and from that of Kennedy and Merchant (who only address degree inversion) in that the landing site is inside the DP. For Borroff and for Kennedy and Merchant, the landing site is the specifier of a functional projection immediately outside the DP. The presence of of they take to require further building, beyond SpecDP. The analysis presented above accommodates the 6 Predicate inversion is not strictly impossible across a negative intervener. For example, (i) below, is certainly not ungrammatical. (i) In these texts will never be found… (Liliane Haegeman, p.c.) This example does not necessarily contradict the generalization that predicate inversion does not cross negative elements. One possibility is that (i) is an instance of heavy-NP shift, as in (ii). (ii) In these texts will never be found a single line from the Incredible String Band’ s hilarious lyrics. 12 optional presence of of without resorting to functional structures outside the DP proper. When it is present, of is in D; when it is not, the indefinite article raises to D. The mechanics of degree inversion and negative inversion have been covered. There are, however, two challenges that are worth addressing, even though I will not attempt to solve them here. The first is the “ trapping” of degree features, and the second is the different behavior that degree words exhibit at the clausal level (compared with their behavior inside the DP). 11. The “trapping” of features In a simple example in which a degree word and adjective are predicated of a noun, DP-internal raising of the degree word (and pied-piping of the adjective) is required. However, when the degree word + adjective is further modified (by just, far, nearly, not, way…), the degree word may raise, but it is no longer required to raise. This was observed in Matushansky (2002:69). Examples (54) – (58) show that raising is optional in these cases. (54) Jimmie Rodgers is not so impressive (of) a yodeler/a not so impressive yodeler. (55) Steve Prefontaine is just how talented (of) a runner/a just how talented runner? (56) Keeping your left foot hovering above the brake is nearly as common (of) a mistake/a nearly as common mistake. (57) The Cyclone is way too dangerous (of) a roller coaster/a way too dangerous roller coaster. (58) Rappaccini is not that friendly (of) a character/a not that friendly character Examples like these provide evidence that leftmost modifier is indeed the head of the complex predicate. In section 8.2, NEG was shown to head the complex DP-internal predicate in examples like (48a), repeated below. Before any movement occurs, the predicate is as in (50), repeated below. (48a) I do notj think that [sink or swim] is [tj very good (of) a philosophy] (50) NegP NEG XP very AP good This basic structure above holds for the degree-modified predicates— the degree word is the head. When modifiers such as the ones listed above combine with phrases headed by degree words, they become the head of the predicate. If these modifiers were not heads, we would expect that the degree words would continue to function as they always do when they head the predicate (raising would be required). Although these heads do not immediately seem to form a natural class, they do behave the same in that DP-internal raising becomes optional. This optionality with respect to fronting is exhibited at the clausal level by the degree words, which as we have seen behave predictably when they are inside the DP. 12. Degree words at the clausal level In a fairly simple DP, the degree words that, how, as, too, so behave in a uniform manner. They all force fronting, and they pied-pipe the predicative adjective. However, in the clause, the degree words behave differently. None of them require that their container be fronted, but while how and so allow fronting within the clause (it is optional), too, that, and as do not allow fronting. This is shown in examples (59) – (63). (59) So tall (of) a man is he… (that he lost a portion of his legs in Procrustes’ s bed) (60) How fast (of) a runner is he? 13 (61) *As talented (of) a writer is he… (62) *Too angry (of) a man is he… (63) *That bizarre (of) a story is it… This somewhat unpredictable behavior on the part of degree words at the clausal level provides some questions for future research. The fact that these degree words behave differently in that so and how may “ assert themselves” outside of their DP container, while too, that and as may not may have something to do with the depth of embedding within the extended projection of the adjective. Negation patterns together with so and how in that negative DPs may (optionally) front within the clause. Alongside (59) and (60) there are examples like (64). (64) On no account is he going to show us the maps of Mars. Absent evidence that the fronted so and how DPs and the fronted negative phrases actually target different landing sites, Occam’ s Razor predicts that they target the same site. In this way, negative inversion and degree inversion within the DP and at the clausal level can be unified. There is no need in either case for a specialized landing site (one for degree-inverted predicates another for negative-inverted predicates). 13. Conclusion The proposal put forward here strengthens the parallels between the clausal and nominal domain in two main respects. First, predicate inversion occurs in both domains (this contrasts with the view that the adjectives in the degree inverted and negative inverted DPs are attributive). Second, within the DP, the projection targeted by degree inversion and negative inversion is the same, just as within the clause. The fact that the adjectives in these constructions are taken as predicative rather than attributive allows the adjectives and their modifiers to participate in predicate inversion. Predicate inversion, in turn, provides an explanation for the presence in English of the indefinite article in these contexts. The [-PLURAL] feature on the spurious article a is incompatible with plural nouns, compatible, of course, with singular nouns, and compatible with mass nouns, but results in a singular “ universal packager” reading, as in (65). (65) Spending your money on too expensive of a turquoise is a bad idea. Base-generating a NEG inside DP— in particular a NEG that can leave its host— allows for an account of the contrast between examples (5) and (7), repeated below, that is not countercyclic. Negative inversion is licensed locally without violation of the extension condition. (5) *Attila is very good (of) an athlete (7) Attila is not very good (of) an athlete This account also provides a straightforward analysis of more complex examples of negative inversion, as in (48a) and (49a), repeated below. (48a) I do notj think that [sink or swim] is [tj very good (of) a philosophy] (49a) *I do notj think that [tj very good (of) a philosophy]i is [sink or swim] ti Finally, although the precise conditions and restrictions on the movement of NEG remain underdefined, these examples provide the beginnings of an understanding of the path NEG travels when it leaves its merge site and the positions in which it may be lexicalized. 14 References Abney, Stephen. 1987. The English Noun Phrase in its Sentential Aspect. Doctoral dissertation, MIT. Bennis, Hans, Norbert Corver and Marcel den Dikken. 1998. Predication in Nominal Phrases. The Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics 1, 85-117. Borroff, Marianne Law. 2000. Degree Phrase Inversion in the Scope of Negation. CUNY Syntax Supper talk. Bresnan, Joan. 1973. Syntax of the Comparative Clause Construction in English. Linguistic Inquiry 4, 275-343. Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The Minimalist Program. The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass. Corver, Norbert. 1997. Much-Support as a Last Resort. Linguistic Inquiry 28, 119-164. Delsing, Lars-Olof. 1983. The Internal Structure of Noun Phrases in the Scandinavian Languages: A Comparative Study. Doctoral dissertation, University of Lund. Hendrick, Randall. 1990. Operator Movement in NP, in Aaron Halpern (ed.) Proceedings of the 9th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, CSLI Publications, Stanford, 249-264. Kennedy, Christopher and Jason Merchant. 2000. Attributive Comparative Deletion. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 18, 89-146. Matushansky, Ora. 2002. Movement of Degree/Degree of Movement. PhD dissertation, MITWPL. Moro, Andrea. 1997. The Raising of Predicates: Predicative Noun Phrases and the Theory of Clause Structure. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Postal, Paul. 2000. An Introduction to the Grammar of SQUAT. Two lectures presented at The Ohio State University. Ms. NYU. 15