Dystopia -2-

advertisement

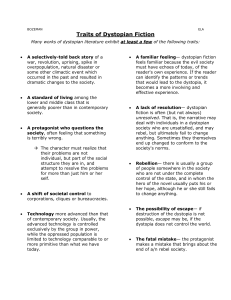

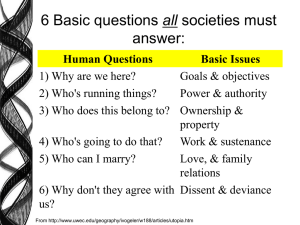

Dystopia -2From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Economics The economic structures of dystopian societies in literature and other media have many variations, as the economy often relates directly to the elements that the writer is depicting as the source of the oppression. However, there are several archetypes that such societies tend to follow. A commonly occurring theme is that the state is in control of the economy, as shown in such works as Ayn Rand's Anthem, Lois Lowry's The Giver, and Henry Kuttner's short story The Iron Standard. Some dystopias, such as Nineteen Eighty-Four, feature black markets with goods that are dangerous and difficult to obtain, or the characters may be totally at the mercy of the state-controlled economy . . . . Even in dystopias where the economic system is not the source of the society's flaws, as in Brave New World, the state often controls the economy. In Brave New World, a character, reacting with horror to the suggestion of not being part of the social body, cites as a reason that everyone works for everyone else. Other works feature extensive privatization and corporatism. In this context, big businesses often have far more control over the populace than any kind of government and thus act as governments themselves instead of businesses, as can be seen in the novel Jennifer Government and the movie Rollerball. This is common in the genre of cyberpunk, such as in Philip K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and Snow Crash, which often features corrupt and all-powerful corporations, often a megacorporation. Caste systems In dystopian literature the advanced technology is controlled exclusively by the group in power, while the oppressed population is limited to technology comparable to or more primitive than what we have today. In order to emphasize the degeneration of society, the standard of living among the lower and middle classes is generally poorer than in contemporary society (at least in United States, Canada or Europe). In Nineteen Eighty-Four, for example, the Inner Party, the upper class of society, also has a standard of living lower than the upper classes of today.[citation needed] In contrast to Nineteen Eighty-Four, in Brave New World and Equilibrium, people enjoy much higher material living standards in exchange for the loss of other qualities in their lives, such as independent thought and emotional depth. Hero Unlike utopian fiction, which often features an outsider to have the world shown to him, dystopias seldom feature an outsider as the protagonist. While such a character would more clearly understand the nature of the society, based on comparison to his society, the knowledge of the outside culture subverts the power of the dystopia. When such outsiders are major characters—such as John the Savage in Brave New World—their societies cannot assist them against the dystopia. The story usually centers on a protagonist who questions the society, often feeling intuitively that something is terribly wrong, such as Guy Montag in Ray Bradbury's novella Fahrenheit 451, Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four, Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games, or V in Alan Moore's V for Vendetta. The hero comes to believe that escape or even overturning the social order is possible and decides to act at the risk of life and limb; in some dystopias[dubious – discuss], this may appear as irrational even to him or her, but he or she still acts. The hero's point of view usually clashes with the others' perception, most notably on Brave New World, revealing that concepts of utopia and dystopia are tied to each other and the only difference between them lies on a matter of opinion. Another popular archetype of hero in the more modern dystopian literature is the Vonnegut hero, a hero who is in high-standing within the social system, but sees how wrong everything is, and attempts to either change the system or bring it down, such as Paul Proteus of Kurt Vonnegut's novel Player Piano or Winston Niles Rumfoord in The Sirens of Titan. Conflict In many cases, the hero's conflict brings him or her to a representative of the dystopia who articulates its principles, from Mustapha Mond in Brave New World to O'Brien in 1984. There is usually a group of people somewhere in the society who are not under the complete control of the state, and in whom the hero of the novel usually puts his or her hope, although often he or she still fails to change anything. In Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four they are the "proles" (Latin for "offspring", from which "proletariat" is derived), in Huxley's Brave New World they are the people on the reservation, and in We by Zamyatin they are the people outside the walls of the One State. In Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury, they are the "book people" past the river and outside the city. Climax and dénouement The hero's goal is to either escape from or destroy the social order. However, the story is often (but not always) unresolved. That is, the narrative may deal with individuals in a dystopian society who are unsatisfied, and may rebel, but ultimately fail to change anything. Sometimes they themselves end up changed to conform to the society's norms, such as in With Folded Hands, by Jack Williamson. This narrative arc to a sense of hopelessness can be found in such classic dystopian works as Nineteen EightyFour. It contrasts with much fiction of the future, in which a hero succeeds in resolving conflicts or otherwise changes things for the better. Destruction The destruction of dystopia is frequently a very different sort of work than one in which it is preserved. Indeed, the subversion of a dystopian society, with its potential for conflict and adventure, is a staple of science fiction stories. Poul Anderson's short story "Sam Hall" depicts the subversion of a dystopia heavily dependent on surveillance. Robert A. Heinlein's "If This Goes On—" liberates the United States from a fundamentalist theocracy, where the underground rebellion is organized by the Freemasons . . . The ability of the protagonists to subvert the society also subverts the monolithic power typical of a dystopia. In some cases the hero manages to overthrow the dystopia by motivating the (previously apathetic) populace. In the dystopian video game Half-Life 2 the downtrodden citizens of City 17 rally around the figure of Gordon Freeman and overthrow their Combine oppressors. Destruction of the fictional dystopia may not be possible, but—if it does not completely control its world—escaping from it may be an alternative. In Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451, the main character succeeds in fleeing and finding tramps who have dedicated themselves to memorizing books to preserve them. But ironically, the dystopian society in Fahrenheit 451 is destroyed in the end — by nuclear missiles. In the book Logan's Run, the main characters make their way to an escape from the otherwise inevitable euthanasia on their 21st birthday (30th in the later film version). Because such dystopias must necessarily control less of the world than the protagonist can reach, and the protagonist can elude capture, this motif also subverts the dystopia's power. In Lois Lowry's The Giver the main character Jonas is able to run away from 'The Community' and escapes to 'Elsewhere' where people have memories. Sometimes, this escape leads to the inevitable: the protagonist making a mistake that usually brings about the end of a rebel society, usually living where people think is a legend.