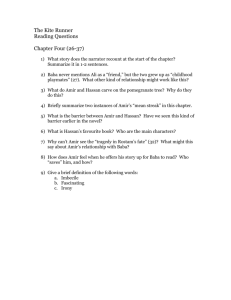

The Kite Runner Review

advertisement

Jack Palmer The Kite Runner Review The Kite Runner reads as an incondite attempt at a profound statement, transformed into something trite and one-sided, with little literary value. It is Hosseini’s first novel, and whilst reading it an undercurrent of editorial intervention is almost palpable. Some aspects of the novel seem promising – notably the section of which covers Amir and Hassan’s childhood. However, this opportunity is lost when there is a sea-change to America. Amir himself has grown up to become a selfindulgent narcissist, his self-absorption evinced in his verbose narrative style, and frequent allusions to events later in the novel: “that day would be the last time he would see Hassan smile.” By the latter stages of the novel, Amir has become an odious character – only concerned with his own moral well-being (and unloading his burden of guilt) than finding any kind of spiritual awakening. Even the title itself – “the Kite” becomes a hackneyed metaphor by the end of the novel. T.S Elliot argued that an ‘Objective Correlative’ can be used to encapsulate an environment, evoke feelings and cast up vivid imagery. As well as this, the Objective Correlative changes in meaning: it often becomes laden with value as a text develops (as we see in Othello where the handkerchief rises from a trivial gift to a symbol of Desdemona’s fidelity). Arguably, the symbol of the “kite” can be deemed a truncated and poorly developed Objective Correlative. It starts off (like the text itself) as reasonably subtle and clever: the kite is a symbol of Hassan and Amir’s childhood gaiety and freedom. But as Amir absconds to America, the symbol is lost (possibly its absence can be seen as a symbol of Taliban repression, although this would be a tenuous reading at best). The novel ends with the symbol returning, although it could be argued that its implantation is an editorial intervention (implied by its cliché nature). Here, quite crudely, the kite is representative of Sohrab’s new found hope. Possibly, if the symbol of the kite was developed on its own, the latter parts of the book would not be so predictable and execrable. However, Hosseini uses the theme of “history repeating self” to the point of gratuity and implausibility. The idea of Assef (who gives Amir Mein Kampf as a birthday present) growing up to be a sadistic, amoral Taliban leader is in itself ludicrous. However, the reader is bombarded with swathes of risible attempts at repetition: Amir having a “hare-lip” like Hassan had; Amir uncovering the fact that Hassan is his step-brother; Amir hiding the money under his driver’s bed (like he did to incriminate Hassan). The result is an unrealistic and pre-empted conclusion, where the reader has a message forced down their throat. It doesn’t offer a balanced argument, and constructs a simplistic fiction of Good vs. Evil. The reader is therefore unable to infer reading, or interpret the story to reflect upon their own morality.