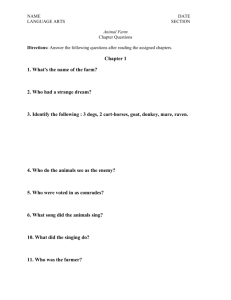

Animal Farm - English Assist Satire

advertisement