read the brief - Mississippi Center for Justice

advertisement

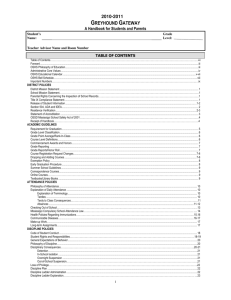

No. 15-666 In the Supreme Court of the United States _________________ TAYLOR BELL, v. Petitioner, ITAWAMBA COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, Respondent. _________________ On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ________________ BRIEF OF MISSISSIPPI CENTER FOR JUSTICE AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER ________________ KIMBERLY JONES MERCHANT BETH L. ORLANSKY MISSISSIPPI CENTER FOR JUSTICE P.O. Box 191 Indianola, MS 38751 (662) 887-6570 DANIEL R. WALFISH Counsel of Record WILL B. DENKER SAGIV Y. EDELMAN MILBANK, TWEED, HADLEY & MCCLOY LLP 28 Liberty Street New York, NY 10005 (212) 530-5000 dwalfish@milbank.com i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................... ii INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE.................... 1 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ............................................................... 1 ARGUMENT ............................................................... 3 I. WHETHER AND HOW SCHOOLS MAY DISCIPLINE STUDENTS FOR OFFCAMPUS SPEECH IS AN IMPORTANT AND RECURRING QUESTION THAT SHOULD BE SETTLED BY THIS COURT ................................................................ 3 II. THE DECISION BELOW GIVES SCHOOL DISTRICTS UNDUE LICENSE TO PUNISH STUDENTS FOR THEIR SPEECH AND THREATENS TO EXACERBATE TROUBLING TRENDS IN SCHOOL DISCIPLINE ....................................................... 7 CONCLUSION .......................................................... 14 ii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Page(s) Cases Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919) ................................................ 5 Ambach v. Norwick, 441 U.S. 68 (1969) .................................................. 5 Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971) .................................................. 4 Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 (1965) ................................................ 3 Hazelwood Sch. Dist. v. Kuhlmeier, 484 U.S. 260 (1988) ................................................ 5 J.S. v. Blue Mountain Sch. Dist., 650 F.3d 915 (3d Cir. 2011) ........................... 6, 7, 8 Layshock v. Hermitage Sch. Dist., 650 F.3d 205 (3d Cir. 2011) ......................... 6, 9, 11 Saxe v. State College Area Sch. Dist., 240 F.3d 200 (3d Cir. 2001) ................................... 3 Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397 (1989) ................................................ 3 Tinker v. Des Moines Indep. Cty. Sch. Dist., 393 U.S. 503 (1969) ..................................... passim iii TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—cont’d Page(s) Watts v. United States, 394 U.S. 705 (1969) ................................................ 4 Statutes and Rules SUP. CT. R. 10(c)........................................................... 6 Other Authorities American Civil Liberties Union & ACLU of Mississippi, Missing the Mark: Alternative Schools in the State of Mississippi (Feb. 2009), https://www.aclu.org/files/pdfs/racialjustic e/missingthemark_report.pdf .............................. 12 Alan Ginsburg et al., Absences Add Up: How School Attendance Influences Student Success, ATTENDANCE WORKS (Aug. 2014), http://tinyurl.com/nje2lbx .................................... 11 Allan Porowski et al., Disproportionality in School Discipline: An Assessment of Trends in Maryland, U.S. DEPT. OF EDUC., INST. OF EDUC. SCIENCES (2014), available at http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs/ projects/project.asp?projectID=365 ..................... 13 iv TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—cont’d Page(s) American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force, Are Zero Tolerance Policies Effective in the Schools? (Aug. 9, 2006), https://www.apa.org/pubs/info/reports/zer o-tolerance-report.pdf (original version) ............. 13 American Psychological Association Zero Tolerance Task Force, Are Zero Tolerance Policies Effective in the Schools?, 63 AM. PSYCHOLOGIST 852 (Dec. 2008) ................ 10, 11, 13 Center for Civil Rights Remedies, Are We Closing the School Discipline Gap? (Feb. 2015), http://tinyurl.com/n5r57c7 .................. 10, 13 Council of State Governments Justice Center, Breaking Schools’ Rules: A Statewide Study of How School Discipline Relates to Students’ Success and Juvenile Justice Involvement (July 2011), https://csgjusticecenter.org/wp-content/ uploads/2012/08/Breaking_Schools_ Rules_Report_Final.pdf ............................... passim Education Law Center-PA, Improving “Alternative Education for Disruptive Youth” in Pennsylvania (Mar. 2010), http://www.elc-pa.org/wpcontent/uploads/2013/12/ELC_AltEdPA_Full Report_03_2010.pdf ............................................. 12 v TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—cont’d Page(s) Lance Lochner & Enrico Moretti, The Effect of Education on Crime: Evidence from Prison Inmates, Arrests, and Self Reports, 94 A. ECON. REV. 155 (Oct. 2003). ............. 11 Mississippi Center for Justice, Overrepresented and Underserved: The Impact of School Discipline on African American Students in Mississippi (forthcoming 2016) ............................................... 13 Russell J. Skiba & M. Karega Rausch, Zero Tolerance, Suspension, and Expulsion: Questions of Equity and Effectiveness, in Handbook of Classroom Management 1063-1089 (Carolyn M. Evertson & Carol S. Weinstein eds., 2006), available at http://www.indiana.edu/~equity/ docs/Zero_Tolerance_Effectiveness.pdf ............... 10 Russell Skiba et al., Consistent Removal: Contributions of School Discipline to the School-Prison Pipeline (May 2003), http://varj.onefireplace.org/Resources/Doc uments/Consistent%20Removal.pdf.................... 11 Texas Appleseed, Texas’ School-to-Prison Pipeline: Dropout to Incarceration (Oct. 2007), http://tinyurl.com/ocvk6qe ........................ 12 vi TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—cont’d Page(s) U.S. Dept. of Justice & U.S. Dept. of Educ., Dear Colleague Letter on the Nondiscriminatory Administration of School Discipline (Jan. 8, 2014)................... passim BRIEF OF MISSISSIPPI CENTER FOR JUSTICE AS AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONER INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE1 The Mississippi Center for Justice (“MCJ”) is a nonprofit, public interest law firm committed to advancing racial and economic justice. MCJ was established in June 2002 in response to the urgent need for advocacy on behalf of low-income people and communities of color; to address the disenfranchisement of blacks, poor whites, Hispanics, and persons with disabilities in Mississippi; and to improve opportunities for low-income, rural, and minority communities. Among MCJ’s concerns is ensuring that Mississippi’s students have access to a quality education. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT Amicus MCJ fights unjust suspensions and expulsions — a phenomenon with enormous but underappreciated social ramifications — to keep students where they belong: In the classroom. In that regard, MCJ has an interest in seeing that school districts impose discipline that (i) complies with constitution1 Counsel of record for all parties received timely notice of amicus Mississippi Center for Justice’s intent to file this brief. Respondent’s written consent to the filing of this brief is being submitted herewith. Petitioner lodged a blanket consent to the filing of amicus briefs. No counsel for a party authored this brief in whole or in part, and no such counsel or party made a monetary contribution intended to fund the preparation or submission of this brief. No person other than the amicus curiae, its members, or its counsel made a monetary contribution intended to fund its preparation or submission. 2 al protections; (ii) is governed by clear standards rather than caprice or unsubstantiated speculation; and (iii) contributes to schools’ educational mission, rather than detracts from it. This case implicates all three imperatives: Taylor Bell, a high school senior with a virtually spotless disciplinary record, was consigned to a scholastic detention center for six weeks as punishment for exercising his First Amendment rights when he posted to the Internet a rap song that he had recorded on his own time and away from school, addressing teacher misconduct that several classmates told him about. Amicus urges this Court to grant review and issue a clear pronouncement on whether and in what circumstances a public school may discipline a student for off-campus speech. The court of appeals believed that Tinker v. Des Moines Independent County School District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969), licensed Respondent (“Itawamba”) to punish Bell for the invective of several of his lyrics. But this Court has never said that Tinker applies to off-campus speech, much less explained how to apply it in the Internet age. The result has been widespread confusion and disagreement within and among the lower courts in an area that implicates fundamental rights as well as the basic mission and role of schools in society. This case thus squarely presents a question that has not been, but emphatically should be, settled by this Court. Without this Court’s intervention, the national confusion generally, and the permissive approach of the Fifth Circuit in particular, invites school boards to impose punishment based on subjective viewpoints as opposed to the even-handed application of clear criteria. Such potential abuse is of particular 3 concern to amicus in light of nationwide pathologies in school discipline: Students are being punished disproportionately (as Bell was), inconsistently across races, and in counterproductive ways that contribute to a troubling phenomenon known as the “school-to-prison” pipeline. This case and others like it are therefore about much more than pure principle. ARGUMENT I. WHETHER AND HOW SCHOOLS MAY DISCIPLINE STUDENTS FOR OFF-CAMPUS SPEECH IS AN IMPORTANT AND RECURRING QUESTION THAT SHOULD BE SETTLED BY THIS COURT A. Bell created his song to express his dismay about, and raise awareness of, misconduct that he felt would be ignored had he reported it to school officials. Pet. App. 7a. The song criticized specific teachers and, implicitly, the school. But protected “‘[s]peech is often provocative and challenging. It may strike at prejudices and preconceptions and have profound unsettling effects as it presses for acceptance of an idea. This is why freedom of speech is protected against . . . punishment. . . . [T]he alternative would lead to standardization of ideas either by legislatures, courts, or dominant political or community groups.’” Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536, 552 (1965) (quoting Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1, 45 (1949)) (emphasis added; internal ellipses omitted); accord Texas v. Johnson, 491 U.S. 397, 408-09 (1989); see also Saxe v. State College Area Sch. Dist., 240 F.3d 200, 215 (3d Cir. 2001) (Alito, J.) (“[T]he mere fact that someone might take offense at the content of speech is not sufficient justification for prohibiting it.”). 4 The en banc majority, which described Bell’s lyrics as “incredibly profane and vulgar,” Pet. App. 5a, lost sight of the fact that it is “often true” — here, literally so — “that one man’s vulgarity is another’s lyric,” Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971). The majority seems actually to have been carried away by its own distaste for Bell’s speech. Pet. App. 36a (“[T]he real tragedy in this instance is that a highschool student thought he could, with impunity, direct speech at the school community which threatens, harasses, and intimidates teachers and, as a result, objected to being disciplined.”). The school district did not marshal a shred of evidence of a threat or even any disruption at the proceedings convened to punish Bell. Nor does there appear to have been any such evidence at the time. To the contrary: Bell was allowed to return to school the next school day after being confronted about his song, and was allowed to remain there until his bus arrived, despite having been informed that he was suspended. See Pet. App. 124a-125a. The school did not contact law enforcement, or take any other security measures. Id. at 97a. To be sure, even though one coach later testified that the song was “just a rap,” id. at 131a, the other said he felt “scared,” id. at 12a. But the second coach did not say who he was scared of (i.e., Bell or others in the community learning of the allegations against him), and in any case this testimony was all after the fact, in the district court, and sheds no light on the basis of the school district’s decision. Without any serious suggestion that Bell issued a “true threat,” cf. Watts v. United States, 394 U.S. 705 (1969), and lacking contemporaneous evidence of disruption, the judges who sided with the school district were forced to come up with a new, more per- 5 missive approach supposedly based on Tinker — even though the speech occurred off campus and this Court has never held that Tinker or any of the Court’s other school-speech precedents applies to offcampus speech. Given the ubiquity of online “social media” and students’ widespread use of it, the Fifth Circuit’s decision risks muzzling students wherever and whenever. The effect of the ruling below — giving school districts enormous power to punish students for their off-hours Internet-based activity — will be to squelch dissenting opinions on matters of concern to the community for fear of reprisal, to stifle artistic expression for fear that it may be misconstrued, and to silence students just as they are beginning to find their voice.2 B. If that is to be the result, it should be because this Court, and not the courts of appeals, issued a clear pronouncement. The applicability of Tinker to 2 The First Amendment is supposed to guard the “marketplace of ideas” against the suppression of counter-majoritarian speech. See Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616, 630 (1919) (Holmes, J., dissenting). In the same vein, public education is designed to “inculcat[e] fundamental values necessary to the maintenance of a democratic political system[.]” Ambach v. Norwick, 441 U.S. 68, 77 (1969). Here, Itawamba did just the opposite: The only “civics lesson,” see Hazelwood Sch. Dist. v. Kuhlmeier, 484 U.S. 260, 277 (1988) (Brennan, J., dissenting), it imparted was that students should be wary of speaking their minds in ways that might be sensitive or unpopular — or just critical of the school. Indeed, the record suggests that Bell’s fellow students got the message. See Pet. App. 98a (Dennis, J., dissenting) (summarizing testimony that “most of the talk amongst students [at Bell’s school] had not been about Bell’s song but rather about his suspension and transfer to alternative school.”). 6 off-campus speech in the Internet age is “an important question of federal law that has not been, but should be, settled by this Court.” SUP. CT. R. 10(c). This Court’s school-speech jurisprudence did not address, and is ill-suited for, contemporary technology. More than forty years have passed since Tinker, and the lower courts are now struggling with whether and how to apply it to means of communication not even imagined by that Court. Absent this Court’s intervention, lower courts will continue to issue conflicting decisions that leave the law unsettled. This case makes the point: It prompted the Fifth Circuit to convene an en banc court that generated three concurrences and four dissents. Judge Prado observed that “off-campus online student speech is a poor fit for the current strictures of First Amendment doctrine,” and expressed his “hope that the Supreme Court will soon give courts the necessary guidance to resolve these difficult cases.” Pet. App. 105a (Prado, J., dissenting). Judge Costa similarly invited clarity: “[T]his court or the higher one will need to provide clear guidance for students, teachers, and school administrators that balances students’ First Amendment rights that Tinker rightly recognized with the vital need to foster a school environment conducive to learning.” Id. at 44a (Costa, J., concurring). The Third Circuit fared no better when it faced similar questions. See Layshock v. Hermitage Sch. Dist., 650 F.3d 205, (3d Cir. 2011) (en banc); J.S. v. Blue Mountain Sch. Dist., 650 F.3d 915, 940 (3d Cir. 2011) (en banc). Two cases that “raise[d] nearly identical First Amendment issues” were taken en banc at the same time, argued on the same day, and decided simultaneously. Layshock, 650 F.3d at 219 n.1 (Jordan, J., concurring). The Third Circuit nev- 7 ertheless issued “competing opinions” — its fifteen judges were almost as fractured as the Fifth Circuit’s sixteen judges — that “thr[ew] into question” the governing law. Id. at 220. Lower courts are begging this Court to speak “clearly, succinctly, and unequivocally.” Pet. App. 39a (Jolly, J., concurring). Given the importance of the issue, the Court should answer their call. II. THE DECISION BELOW GIVES SCHOOL DISTRICTS UNDUE LICENSE TO PUNISH STUDENTS FOR THEIR SPEECH AND THREATENS TO EXACERBATE TROUBLING TRENDS IN SCHOOL DISCIPLINE A. Amicus believes that schools must impose discipline fairly and evenhandedly. To that end, it is essential that schools base their punishment on clear, articulable standards, rather than on whim or personal predilection. Amicus is concerned that the ruling below provides few meaningful checks on a school board’s ability to punish a student for his or her off-campus speech, and, as the en banc court’s lead dissent explained, fails to give “adequate notice of when [a student’s] off-campus speech crosses the critical line between protected and punishable expressions.” Pet. App. 74a. First, the majority’s focus on whether a student intended for off-campus speech to reach the ears of members of the school community invites mischief. Id. As a Third Circuit five-judge concurrence explained, “speech originating off campus does not mutate into on-campus speech simply because it foreseeably makes its way onto campus. A bare foreseeability standard could be stretched too far, and would risk ensnaring any off-campus expression that happened to discuss school-related matters.” J.S., 650 8 F.3d at 940 (Smith, J., concurring) (citations omitted). Only through such “mutation” could Bell’s song — which he recorded at a professional studio and disseminated using his personal computer at home, posted to a medium that could not be accessed on campus, and did not play or perform at school — be considered cause for punishment by a school. Pet. App. 122a-123a. Second, the majority’s focus on whether school officials “reasonably could find” artistic expression “threatening, harassing, and intimidating,” Pet. App. 19a, 30a (itself a gloss on Tinker’s requirement of a reasonable forecast of a substantial disruption), also invites decisions based on unduly subjective sensibilities. It is all too easy under this framework for a school to silence expression that it disagrees with or dislikes, instead of having to base its decision on the existence of objective evidence of a bona fide disruption to the education environment. Bell’s case highlights the problem: He was suspended for six weeks for a song that caused no real disruption. Id. at 98a & n.23. B. In fact, Bell’s case is an object lesson in the pathologies of school discipline — pathologies that make further review of the decision below that much more pressing. The argument is sometimes made that schools should be given a freer hand in disciplining students for their speech so as to protect the educational environment. See, e.g., Pet. App. 22a-23a. What happened here, though, is that far from fulfilling its mission to protect students, Itawamba actually abdicated its responsibility to provide a productive learning environment for a non-violent student. 9 Disproportionate punishment in schools is a major problem across the country. The U.S. Departments of Education and Justice recently observed that schools are using exclusionary discipline — inschool and out-of-school suspensions, expulsions, or referrals to law enforcement authorities — with increasing frequency.3 Here, Bell was consigned to an “alternative school” — an institution designed for students with real behavior problems — for an extended period of time just for writing and posting a song. There was no suggestion that Bell had any violent background or propensity, or posed any danger to anyone. Bell’s story is not unique. In Layshock, for example, the plaintiff student “was classified as a gifted student, was enrolled in Advanced Placement classes, and had won awards at interstate scholastic competitions.” 650 F.3d at 210 & n.6. For creating an Internet “parody profile” of his principal, he was sentenced to spend most of the second half of the school year in an Alternative Education Program “reserved for students with behavior . . . problems who are unable to function in a regular classroom.” Id. This prompted a unanimous en banc court to wonder “how the School District determined that it was appropriate to place such a student in a program designed for students who could not function in a classroom.” Id. A growing body of research calls the value of school suspensions into question. Most suspensions 3 U.S. Dept. of Justice & U.S. Dept. of Educ., Dear Colleague Letter on the Nondiscriminatory Administration of School Discipline 4 (Jan. 8, 2014) (hereinafter Dear Colleague Letter). 10 are for nonviolent infractions,4 making it difficult to argue that suspensions make schools safer. In fact, according to the American Psychological Association (“APA”), the data do not show a clear link between, on the one hand, the use of suspension, expulsion, or so-called “zero-tolerance” policies — under which often severely punitive “predetermined consequences” follow regardless of the gravity of misbehavior, context, or mitigating circumstances — and, on the other, improvements in student behavior or school safety.5 Instead, studies have shown that the schools that frequently suspend and expel students have worse school climates and governance structures, spend a disproportionate amount of time on disciplinary matters, and, even controlling for demographic factors, fare worse on state accountability tests.6 4 See Center for Civil Rights Remedies, Are We Closing the School Discipline Gap?, 10 & n.14 (Feb. 2015), http://tinyurl.com/n5r57c7 (hereinafter Closing the School Discipline Gap); see also Council of State Governments Justice Center, Breaking Schools’ Rules: A Statewide Study of How School Discipline Relates to Students’ Success and Juvenile Justice Involvement 37-38 (July 2011), https://csgjusticecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/ Breaking_Schools_Rules_Report_Final.pdf (hereinafter Breaking Schools’ Rules) (a study of public school suspensions in Texas found that more than 90% of all suspensions were discretionary suspensions for violations of school codes of conduct). 5 APA Zero Tolerance Task Force, Are Zero Tolerance Policies Effective in the Schools?, 63 AM. PSYCHOLOGIST 852, 854 (Dec. 2008) (hereinafter APA, Zero Tolerance Policies). 6 Id.; Russell J. Skiba & M. Karega Rausch, Zero Tolerance, Suspension, and Expulsion: Questions of Equity and Effectiveness, in HANDBOOK OF CLASSROOM MANAGEMENT 1063-1089, 1072 (Carolyn M. Evertson & Carol S. Weinstein eds., 2006), at http://www.indiana.edu/~equity/docs/Zero_ available 11 Exclusionary discipline is also associated with an increase in behavioral problems, academic difficulty, detachment from school, and dropout rates.7 C. Extreme school punishments are also intertwined with the phenomenon known as the “schoolto-prison-pipeline.” Time spent out of school (resulting, for example, from a suspension) is a significant factor in predicting juvenile delinquency and incarceration.8 Suspensions, as noted above, are associated with increased drop-out rates, and students who drop out of school are more likely to be incarcerated.9 Alternative schools, like the one to which Bell and the Layshock plaintiff were consigned, have problems of their own. A 2009 report by the American Civil Liberties Union (“ACLU”) and the ACLU of Mississippi concluded that Mississippi’s alternative [Footnote continued from previous page] Tolerance_Effectiveness.pdf; see also Alan Ginsburg et al., Ab- sences Add Up: How School Attendance Influences Student Success 3, ATTENDANCE WORKS (Aug. 2014), http://tinyurl.com/nje2lbx (finding that students that had missed three or more days in the month before taking the National Assessment of Educational Progress had lower average scores than students with fewer absences). 7 APA, Zero Tolerance Policies, at 854; Breaking Schools’ Rules 59; Dear Colleague Letter 4 (noting that studies demonstrate a correlation between exclusionary discipline and “an array of serious educational, economic, and social problems.”). 8 Russell Skiba et al., Consistent Removal: Contributions of School Discipline to the School-Prison Pipeline 27-28 (May 2003), at http://varj.onefireplace.org/Resources/Documents/ Consistent%20Removal.pdf. 9 Lance Lochner & Enrico Moretti, The Effect of Education on Crime: Evidence from Prison Inmates, Arrests, and Self Reports, 94 A. ECON. REV. 155 (Oct. 2003). 12 schools “[t]oo often . . . hurt the very students they are meant to help.”10 They overemphasized punishment at the expense of remediation; lacked the same academic standards as “mainstream” schools; and were inadequately staffed.11 Similar phenomena exist in other states.12 D. There are documented racial disparities in the imposition of school discipline — another reason why clear standards and even-handed treatment are so important. Studies reveal that where discretionary punishment is concerned, black students are more likely than white students to be punished for the same offense.13 Investigations conducted by the U.S. Departments of Education and Justice “revealed racial discrimination in the administration of stu10 ACLU & ACLU of Mississippi, Missing the Mark: Alternative Schools in the State of Mississippi, 6 (Feb. 2009), https://www.aclu.org/files/pdfs/racialjustice/missingthemark_ report.pdf. 11 See id. at 8. 12 A study of Texas’s Disciplinary Alternative Education Programs (“DAEPs”), for example, revealed that many students in DAEPs did not receive teacher-led instruction but instead were given packets of worksheets to complete. Not every DAEP had a library, and students were seldom provided access to advanced curriculum and could not take their textbooks home. Texas Appleseed, Texas’ School-to-Prison Pipeline: Dropout to Incarceration 31-32 (Oct. 2007), http://tinyurl.com/ocvk6qe. A 2010 report on Pennsylvania’s program of alternative education for disruptive youth identified similar problems. See Education Law Center-PA, Improving “Alternative Education for Disruptive Youth” in Pennsylvania, (Mar. 2010), http://www.elcpa.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/ ELC_AltEdPA_FullReport_03_2010.pdf. 13 Breaking Schools’ Rules 44-45; see also Dear Colleague Letter 4 (collecting sources). 13 dent discipline” and “found cases where AfricanAmerican students were disciplined more harshly and more frequently because of their race than similarly situated white students.”14 This discrepancy is likely due at least in part to the implementation of zero-tolerance disciplinary policies.15 Regardless of whether Taylor Bell’s punishment would have been any different had he been white, the fact remains that black students suffer from inequitable disciplinary treatment across the 14 Dear Colleague Letter 4; see also MCJ, Overrepresented and Underserved: The Impact of School Discipline on African American Students in Mississippi 21 (forthcoming 2016) (finding that, within a sample of demographically diverse Mississippi school districts, black students were more than three times as likely to receive an out-of-school suspension as white students); Allan Porowski et al., Disproportionality in School Discipline: An Assessment of Trends in Maryland 9, U.S. DEPT. OF EDUC., INST. OF EDUC. SCIENCES (2014), available at http://ies.ed.gov/ ncee/edlabs/projects/project.asp?projectID=365 (finding that black students experienced higher rates of out-of-school suspension than white students for the same infractions); Breaking Schools’ Rules 5 (finding that black students were almost three times more likely than white students to receive an out-ofschool suspension for their first disciplinary violation). 15 Zero-tolerance policies were first implemented in the early 1990s. See APA, Zero Tolerance Policies, at 852. In 1988-1989, 10% of black students and 4% of white students were suspended; in 2011-2012, 16% of black students and 5% of white students were suspended. Closing the School Discipline Gap 5. And “[d]ata since 1995 indicate that the application of zero tolerance policies does not appear to have reduced, and indeed may have exacerbated, . . . disciplinary disproportionality [among students of color].” APA Zero Tolerance Task Force, Are Zero Tolerance Policies Effective in the Schools? 64 (Aug. 9, 2006), https://www.apa.org/pubs/info/reports/zero-tolerancereport.pdf (original version). 14 country, and that many students are harmed by schools’ overreliance on exclusionary discipline. The systemic problems with school disciplinary systems, and the potential for abusing them, make it all the more important that this Court issue clear guidance as to the circumstances in which a school may punish a student for exercising his freedom of speech outside of the school environment. CONCLUSION The Petition for a Writ of Certiorari should be granted. Respectfully submitted. KIMBERLY JONES MERCHANT BETH L. ORLANSKY MISSISSIPPI CENTER FOR JUSTICE P.O. Box 191 Indianola, MS 38751 (662) 887-6570 DANIEL R. WALFISH Counsel of Record WILL B. DENKER SAGIV Y. EDELMAN MILBANK, TWEED, HADLEY & MCCLOY LLP 28 Liberty Street New York, NY 10005 (212) 530-5000 dwalfish@milbank.com Counsel for Amicus Curiae December 2015