Brief - Thomas Jefferson Center

advertisement

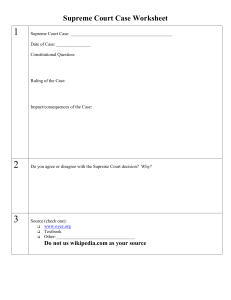

STATE OF MICHIGAN COURT OF APPEALS _______________________________ THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF MICHIGAN, Plaintiff-Appellee, v. Court of Appeals No. 225747 Circuit Court No. 99-6546-AR District Court No. 98-1728-SM TIMOTHY JOSEPH BOOMER, Defendant-Appellant. _______________________________ Richard E. Vollbach, Jr. (P46137) Attorney for Plaintiff-Appellee Arenac County Prosecutor's Office 120 N. Grove Street P.O. Box 1309 Standish, MI 48658 517-846-4597 Michael J. Steinberg (P43085) Kary L. Moss (P49759) Attorney for DefendantAppellant ACLU Fund of Michigan 1249 Washington Blvd. Suite 2910 Detroit, MI 48226 313-961-7728 _____________________________ _______________________________ ________________ AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF IN SUPPORT OF DEFEND ANT-APPELLANT'S APPLICATION FOR LEAVE TO APPEAL Attorneys for Amicus Curiae Elizabeth A. Cabot (P36677) Robert M. O'Neil Sachs, Waldman, O'Hare, J. Joshua Wheeler Helveston, Bogas & Mclntosh, P.C. Thomas Jefferson Center for the 1000 Farmer Protection of Free Expression Detroit, MI 48226 400 Peter Jefferson Place 313-965-3464 Charlottesville, VA 22911 804-295-4784 TABLE OF CONTENTS INDEX OF AUTHORITIES ii SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT 1 ARGUMENT 3 I. THE CIRCUIT COURT'S INTERPRETATION OF MCL 750.337 VIOLATED FUNDAMENTAL FIRST AMENDMENT PRINCIPLES A. The Circuit Court Confused the Facial and As-Applied Challenges to MCL 750.337 by Narrowing and Then Impermissibly Expanding the Scope of that Statute. 3 The Judicial Precedent from Michigan and Other Jurisdictions Cited by Appellee and Relied Upon by the Courts Below Do Not Support Extending the Reach of MCL 750.337 to Language Other than Obscenity and "Fighting Words." 4 Mr. Boomer's Speech Is Protected Under the First Amendment. 9 THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT HAS CLEARLY STATED THAT THE STATE MAY NOT REDUCE PUBLIC DISCOURSE TO THAT WHICH IS FIT FOR CHILDREN. 12 ONLY BY DISREGARDING THE SUPREME COURT'S HOLDING IN COHEN V. CALIFORNIA CAN MR. BOOMER'S CONVICTION BE AFFIRMED. 14 B. C. II. III. 3 CONCLUSION 16 APPENDIX A i INDEX TO AUTHORITIES Case Page Bolgers v. Youngs Drug Prods. Corp., 463 U.S. 60 (1983) ..................................................13 Breaux v. State, 230 Ga. 506 (1973) .........................................................................................9 Butler v. Michigan, 352 U.S. 380 (1957) ................................................................................ 12 Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568 (1942) .........................................................8, 10 City of Macon v. Smith, 244 Ga. 157 (1979) ................................................................ 6, 7, 9 City of Oak Park v. Smith, 79 Mich. App. 757 (1977) ..............................................................6 City of Pontiac v. Klein, 67 Mich. App. 556 (1976) ................................................................5 Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971) ................................................ 1, 9, 10, 11, 14. 15, 16 Cottage Grove v. Farmer, 42 Or. App. 21 (1979) .....................................................................7 Cyberspace Communications, Inc. v. Engler, 55 F. Supp. 2d 737 (E.D. Mich. 1999)...............12 East Peoria v. Moushon, 45 111. App. 3d 719 (1977) ................................................................7 Erznoznik v. Jacksonville, 422 U.S. 205 (1975) .......................................................................13 Gooding v. Wilson, 405 U.S. 518 (1972)..................................................................................10 Meyer v. Grant, 486 U.S. 414 (1988 ........................................................................................15 Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973) ................................................................................ 8 New York v. Ferber, 458 U.S. 747 (1982) .............................................................................13 People v. Boomer, No. 99-6546-AR (Feb. 17, 2000) ................................................................5 People v. Boomer, No. 98-1728-SM (Feb. 8, 1999) ................................................................8 People v. Price, 4 Cal. App. 3d 941 (1970) ............................................................................ 8 ii Prak v. Gregart, 749 F. Supp. 825 (E.D. Mich.1990) .............................................................5 R.A.V. v. St. Paul, 505 US 377 (1992)...................................................................................... 10 Reno v. ACLU, 521 U.S. 844 (1997) ................................................................................. 12, 13 Sable Communications of Cal., Inc. v. FCC, 492 U.S. 115 (1989)........................................13 State v. Orange, 22 N.C. App. 220 (1974) ................................................................................ 7 State v. Profaci, 56 N. J. 346 (1970) .........................................................................................8 White v. Norwalk, 900 F.2d 1421 (9th Cir. 1990) ..................................................................7 Statutes MCL 750.337 .................................................................................................................. passim Constitution US Const. Am I ................................................................................................................ passim iii SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT “[O]ne man's vulgarity is another's lyric.” Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15, 25 (1971). The meaning of that statement is clear — what is a meaningless and offensive term to one person can be meaningful and eloquent to another. But under the theory put forth by Appellee, only speech that conveys a meaningful idea is protected by the First Amendment. Thus, according to Appellee, if one man's lyric is another's vulgar lyric, it is no longer protected by the First Amendment. Such an interpretation is completely at odds with the clear import of Cohen. In labeling Timothy Boomer a criminal for offensive words alone, the circuit court departed from basic principles of the First Amendment in an unconstitutional attempt to reduce the public discourse to that which is fit for children. To uphold the conviction, the circuit court had to engage in an awkward legal two-step — first narrowing the scope of MCL 750.337 to save it from a facial challenge, and then expanding the reach of the statute to apply to conduct that is not covered by its provisions. In so doing, the circuit court made the illogical determination that Mr. Boomer’s spoken words did not constitute speech at all and thus fell outside the umbrella of First Amendment protection. By creating an additional category of unprotected speech, the circuit court violated the Supreme Court’s clear instruction that a state may not punish speech unless it falls within a discrete and narrowly defined exception to the free speech protections embodied in the Constitution. As Mr. Boomer’s speech does not fall within any such exception, this Court should grant his Application for 1 Leave to Appeal.1 _________________________ 1 Amicus agrees with Appellant that MCL 750.337 is unconstitutional on its face. There is no need to address that issue here, however, because it is comprehensively addressed in Appellant’s Application for Leave to Appeal. Rather, this brief will focus on the fundamental inconsistencies and mistakes of law made by the lower courts and the Appellee. 2 ARGUMENT I. THE CIRCUIT COURT'S INTERPRETATION OF MCL 750.337 VIOLATED FUNDAMENTAL FIRST AMENDMENT PRINCIPLES. The Circuit Court Confused the Facial and As-Applied Challenges to MCL 750.337 by Narrowing and Then Impermissibly Expanding the Scope of that Statute. As this Court is well aware, a First Amendment challenge to a finding of guilt under a criminal statute may take two forms—a challenge to the constitutionality of the statute itself or a claim that a lower court applied the statute in an unconstitutional manner. Both the lower courts' decisions in this case, as well as Plaintiff/Appellee’s Response to Defendant/Appellant’s Application for Leave to Appeal, display a confusion between the analysis required to defend the facial validity of a statute and the analysis needed to justify the application of MCL 750.337 to Mr. Boomer’s words. The circuit court, in a ruling read from the bench,2 affirmed the district court’s holding that narrowed the reach of MCL 750.337 to expression falling in the lesser-protected categories of obscenity or fighting words. Nevertheless, the circuit court, having endorsed the district court’s response to the facial challenge to MCL 750.337, 3 curiously proceeded to allow an expansion of the reach of the statute by applying it to expression that is neither ____________________________ 2 The circuit court did not issue a written opinion, but rather, in response to defense counsel’s inquiry as to whether there would be “a written decision of any nature,” merely stated that “[t]he court reporter has been present throughout this entire hearing.” Oral Argument Transcript, at 33. 3 The circuit court did not address the district court's narrowing of the statue. It merely agrees that MCL 750.337 is constitutional on its face. See Oral Argument Transcript, at 29 (“If a statute is constitutional, which this Court finds that this one is, as specifically applied to this case, at least....”). 3 obscene nor fighting words. The State cannot have it both ways. Either MCL 750.337 is unconstitutional on its face, or its application must be limited to speech that is either obscene or fighting words. The district court held that Mr. Boomer’s speech did not fall into either category — a holding that has not been challenged on appeal. Once those findings were made, the prosecution against Mr. Boomer should have ended. Even if Amicus conceded (which it does not) that Mr. Boomer’s expression was not protected under the First Amendment, it was reversible error to prosecute him under a statute that did not apply to his speech. B. The judicial precedent from Michigan and other jurisdictions cited by Appellee and relied upon by the courts below do not support extending the reach of MCL 750.337 to language other than obscenity and “fighting words.” Modern First Amendment jurisprudence is rooted in the simple, yet profound, notion that all words—whether they comport with or depart from societal norms of civility and decency, whether they voice a popular or disfavored sentiment, and indeed, even if they voice no apparent sentiment at all—are presumed to be constitutionally protected unless they fall within a few discrete and narrowly defined categorical exceptions. By characterizing Mr. Boomer's speech as some sort of “non-speech” that is not entitled to protection under the First Amendment, the circuit court violated this fundamental principle. Though the circuit court did not repeat the term “non-speech” as coined by the district court to describe the words spoken by Mr. Boomer, it clearly endorsed the illogical concept that some spoken words can properly be considered not to be speech as protected by the First Amendment. The circuit court stated: [T]he conduct that Mr. Boomer was convicted for was determined by the district court, 4 and rightly so, not to be speech as protected by and thought of under the First Amendment of the United States Constitution. Every noise and/or utterance does not constitute protected free speech that falls within the protection umbrella of the First Amendment. Oral Argument Transcript, People v. Boomer, No. 99-6546-AR (Feb. 17, 2000) (hereinafter “Transcript”) at 30 (emphasis added); see also id. at 32 (“All noise is not protected speech.”). The circuit court engages in what can only be described as legal alchemy by transforming Mr. Boomer's verbal expression of vulgar but commonly understood words into a form of “nonspeech.” That this argument is legally untenable is evidenced by the fact neither the lower courts nor the Appellee cite one case that directly supports this analytical sleight-of-hand. Indeed, systematic examination of the cases cited by Appellee (Response, Argument IV, at 2324) reveals that, in extending the reach of MCL 750.337, the lower courts failed to defer to federal and state court precedent. In Prak v. Gregart, a defendant made a facial challenge in federal court to the constitutionality of MCL 750.337. 749 F. Supp. 825 (E.D. Mich.1990). Although the federal court refused to rule that the state statute was unconstitutional on its face, the court’s holding was based in the finding “that a Michigan court may limit application of the statute to ‘fighting words.’” Id. at 829 (emphasis added). In City of Pontiac v. Klein, 67 Mich. App. 556 (1976), the Michigan Court of Appeals assessed the constitutionality of a statute similar to MCL 750.337 which prohibited “indecent, profane, or obscene language in the presence of others.” The defendants in Klein submitted jury instructions requesting the jury to convict only if they found the defendants to have 5 uttered “fighting words.” 67 Mich. App. at 557. The trial court rejected this request and instructed the jury to convict if they found the defendants’ language to be merely “grossly vulgar or profane.” Id. at 558. The Michigan Court of Appeals reversed finding that the jury instructions did not limit the application of the statute to fighting words. In City of Oak Park v. Smith, 79 Mich. App. 757, 761 (1977), the Michigan Court of Appeals was confronted with a city ordinance that read: “It shall be unlawful for any person to insult, accost, molest, or otherwise annoy, either by word of mouth, sign, or motion, any person in any public place.” Following Klein, the court found the ordinance constitutional only if its application was limited to “fighting words.” See City of Oak Park, 79 Mich. App. at 762. Appellee cites to a number of other jurisdictions where statutes or ordinances criminalizing profane or obscene language had been upheld as constitutional. Close scrutiny of these decisions, however, reveals a cautious and narrow application of these provisions unlike that applied by the lower courts to MCL 750.337. For example, Appellee cites City of Macon v. Smith, 244 Ga. 157 (1979), as an example of a court upholding the constitutionality of an ordinance prohibiting profanity. It is the exact outcome of that case, however, that would dictate the reversal of Mr. Boomer’s conviction under MCL 750.337. In City of Macon, the Georgia Supreme Court analyzed a local ordinance which provided: “It shall be unlawful for any person to act in a violent, turbulent, boisterous, indecent or disorderly manner or to use profane, vulgar, or obscene language in the city, tending to disturb good order, peace, and dignity in said city.” City of 6 Macon, 244 Ga. at 159. The court, despite finding defendant's conduct and language “vulgar and offensive,” refused to characterize her remarks as “fighting words.” Id. at 159. Accordingly, since the trial court had convicted the defendant on grounds other than “fighting words,” the court held the statute to be unconstitutionally applied. Id. At issue in East Peoria v. Moushon, 45 111. App. 3d 719 (1977), was an ordinance prohibiting obscene, offensive, or profane language. The Illinois court found the constitutionality of the ordinance to rest on a narrow interpretation. “Admittedly, vulgar or profane words alone are not sufficient to permit criminal prosecution unless they are ‘fighting words.’” Id. at 722-23. In Cottage Grove v. Farmer, 42 Or. App. 21, 22 (1979), the court upheld an ordinance defining disorderly conduct as someone whom “uses abusive or obscene language, or makes an obscene gesture likely to provoke a violent or disorderly response.” Imperatively, this statute contains the phrase, “likely to provoke a violent or disorderly response.” Id. Without this demand for such “fighting words,” this statute would have likely been found overbroad in its application. In State v. Orange, 22 N.C. App. 220, 223 (1974), the statute in question also had a clause demanding a provocation of incitement. In complying with that state’s precedents, the court construed the statute to prohibit “only words and conduct likely to provoke ordinary men to violence.” Id. (emphasis added). At issue in White v. Norwalk, 900 F.2d 1421, 1424 (9th Cir. 1990), was a California locality’s ordinance that permitted the prosecution of any person who, at a city council 7 meeting, “makes such remarks, or who utters loud, threatening, personal or abusive language.” Although the Ninth Circuit found the ordinance constitutionally valid, it did so only after noting they were “not dealing with words uttered on the street to anyone who chooses or chances to listen; we are dealing with meetings of the Norwalk City Council. Principles that apply to random discourse may not be transferred without adjustment to this more structured situation.” Id. at 1425. Thus, the ordinance retained its validity due to the council-meeting environment in which it was limited. See id. Appellee also points to People v. Price, 4 Cal. App. 3d 941 (1970), as evidence of the constitutionality of a statute that prohibits obscenity. Restrictions on obscenity, of course, are acceptable under the doctrine of Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15 (1973). Moreover, the issue is irrelevant to the instant case because Judge Yenior correctly determined that Mr. Boomer’s language falls outside the purview of obscenity. See People v. Boomer, No. 981728-SM (Feb. 8, 1999), at 3. Only two of the eight cases from other jurisdictions cited by actually accepted the constitutionality of their respective statutes without limiting their application to obscenity or “fighting words.” In State v. Profaci, 56 N.J. 346 (1970), the court relied on Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire in ruling that the statute in question was constitutional because its purpose was to “preserve the peace.” 315 U.S. 568, 353 (1942). The court held that this purpose included protecting “the sensibilities of those persons within hearing of the person uttering the language.” Id. But it must be noted that the New Jersey Supreme Court decided Profaci in 1970. The constitutional validity of criminalizing words that offend the individual 8 “sensibilities” of persons is highly questionable after the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1973 decision in Cohen v. California. Similarly, the persuasiveness of the Georgia Supreme Court’s decision in Breaux v. State, 230 Ga. 506, 508 (1973), has been tempered by that court’s 1979 decision in Macon v. Smith (discussed supra., p. 19). In Breaux, the court upheld an ordinance making criminal comments that are “obscene, vulgar, or profane.” “Language is obscene, vulgar, or profane when, under the circumstances and manner in which such utterance was made, it would clearly offend a reasonable person's sense of decency.” Id. As the dissent noted, this definition of vulgar and profane language is too subjective, giving the statute an unconstitutionally vague and overbroad construction. Id. at 510 (Gunter, J., dissenting). Further, this open-ended definition of profane and vulgar is inconsistent with the more narrow application required by the Georgia Supreme Court of a similar ordinance in Macon. 244 Ga. at 159. Thus, there is little, if any, judicial authority that supports the extension of a statute such as MCL 750.337 to expression other than obscenity or “fighting words.” Indeed, these cases require that the reach of the statutes be limited to these categories in order to survive a facial attack. When the district court specifically found that Mr. Boomer’s speech did not constitute obscenity or “fighting words,” the prosecution against him should have been dismissed. C. Mr. Boomer's Speech Is Protected Under the First Amendment. Instead of grounding its holding in the relevant case law—all of which supports exactly 9 the opposite conclusion of that reached by the circuit court—the circuit court's treatment of Mr. Boomer's words appears to be based on a normative judgment of the communicative value of Mr. Boomer's expression. However, to regulate speech based on this factor is clearly impermissible. Even if some categories of unprotected speech might seem to share a diminished or attenuated communicative value, it is incorrect to assume that all speech having such a characteristic is unprotected because of that trait alone. Rather, the presumption created by the First Amendment is that speech is fully protected unless it falls into a clearly defined and established category of unprotected expression. Gooding v. Wilson, 405 U.S. 518, 521-22 (1972) (quoting Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U.S. 568, 571 (1942); see also Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15, 19-20 (1971). For instance, it is clear that words that are integral to a criminal conspiracy, solicitation or aiding and abetting are unprotected. In addition, the Supreme Court has held that expression that constitutes “fighting words,” child pornography, defamation, or is legally obscene is not accorded First Amendment protection. Beyond these limited classes of exceptions, however, the Supreme Court has repeatedly cautioned that “the constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech forbid the States to punish the use of words or language.” Id. There is simply no recognized exception to First Amendment protection for verbal expression that is labeled “non-speech.” Indeed, in R.A. V. v St. Paul, the Supreme Court explicitly rejected a similar proposition: We have sometimes said that . . . categories of expression “are not within the area of constitutionally protected speech,” or that “the protection of the First Amendment does not extend” to them. Such statements must be taken in context, however, and are no more literally true than is the occasionally repeated shorthand characterizing obscenity “as not being speech at all.” 10 505 U.S. 377, 384 (1992) (emphasis added) (citations omitted). The claim that purely verbal expression of commonly understood words is “non-speech” is both constitutionally and logically untenable. The words Mr. Boomer uttered were highly offensive, but only that. As evidenced by the additional elements that are always required for speech to be deemed obscene or fighting words, offensiveness by itself does not strip speech of its First Amendment protection. There is also a factually-based flaw in the lower courts’ analyses. It is far from obvious on the record that the defendant’s outburst was devoid of meaning or message. Had that been as clear as the lower courts seemed to believe it was, listeners presumably would have reacted with ridicule, humor or even compassion, and not with anger or hostility. Indeed, the very premise underlying MCL 750.337 is that certain words are so charged with meaning and content to listeners that the Michigan Legislature deemed their utterance worthy of punishment. MCL 750.337 seems a rational expression of legislative decisionmaking only on the assumption that “indecent” or “immoral” language, among others, is virtually certain to have some cognitive or emotive impact on listeners. Unlike, for example, content-neutral noise ordinances that restrict the use of words regardless of meaning or cognitive or emotive impact on listeners, the very offense being targeted by the State in this case springs from the content of Mr. Boomer’s words—that is, from the listener’s likely higher-order recognition of what Mr. Boomer’s words mean in context. In this case as well as in Cohen, “[t]he only ‘conduct’ which the State sought to punish is the fact of communication.” Cohen, 403 U.S. at 18. 11 II. THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT HAS CLEARLY STATED THAT THE STATE MAY NOT REDUCE PUBLIC DISCOURSE TO THAT WHICH IS FIT FOR CHILDREN. To conform with MCL 750.337, a communicant must use only language suitable for children. However, the United States Supreme Court has emphatically declared that the government may not defend its suppression of constitutionally protected speech under the claim of protecting children because this design would “burn the house to roast the pig.” Butler v. Michigan, 352 U.S. 380, 383 (1957); see also Cyberspace Communications, Inc. v. Engler, 55 F. Supp. 2d 737, 747-48 (E.D. Mich. 1999). In 1957, in Butler v. Michigan, the Supreme Court considered a Michigan statute making it an offense to make available to the general public any book that would “tend[] to the corruption of the morals of youth.” Butler, 352 U.S. at 525. The Supreme Court found that “[t]he incidence of the enactment is to reduce the adult population of Michigan to reading only what is fit for children[,]” thereby limiting an individual freedom guaranteed by the Constitution. Id. at 526. For the subsequent forty years, the Supreme Court has consistently maintained that the First Amendment does not tolerate the restriction of the constitutionally protected speech of adults to protect minors from hearing such speech. See Reno v. ACLU, 521 U.S. 844 (1997) (striking down provisions of the Communications Decency Act prohibiting transmission of obscene or indecent communications on the Internet to persons under age eighteen on the grounds that the provisions were unconstitutional content-based blanket restrictions on speech); Sable Communications of Cal., Inc. v. FCC, 492 U.S. 115 (1989) (striking down a federal law criminalizing the transmission of indecent, but nonobscene, commercial telephone messages to minors and adults); Bolgers v. 12 Youngs Drug Prods. Corp., 463 U.S. 60 (1983) (striking down a federal law prohibiting the mailing of unsolicited advertisements for contraceptives); Erznoznik v. Jacksonville, 422 U.S. 205 (1975) (rejecting city's argument that ordinance penalizing drive-in movie theaters for showing nudity in films visible to passersby was justified for the protection of children). Contrary to the claims of Appellee, the protections afforded children against child pornography have absolutely nothing to do with this case. Child pornography, as opposed to pornography involving only adults, is accorded a lower standard of protection because the “distribution of photographs and films depicting sexual activity of children is intrinsically related to sexual abuse...” New York v. Ferber, 458 U.S. 747, 759 (1982)(emphasis added). In producing child pornography, there is an obvious and tangible harm to the children involved. To equate that harm with the harm a child allegedly suffers from hearing someone curse demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of the basis for excluding child pornography from First Amendment protection. In Reno v. ACLU, the Supreme Court stated, “[t]he interest in encouraging freedom of expression in a democratic society outweighs any theoretical but unproven benefit of censorship.” 521 U.S. at 885. Mr. Boomer cannot be deprived of his constitutionally protected speech rights to shelter children from language the State finds offensive. 13 III. ONLY BY DISREGARDING THE SUPREME COURT'S HOLDING IN COHEN V. CALIFORNIA CAN MR. BOOMER'S CONVICTION BE AFFIRMED. The conviction of Mr. Boomer is clearly at odds with the principles articulated in Cohen v. California. Appellee seeks to distinguish this case from Cohen on the grounds that Mr. Cohen's expression of “Fuck the Draft” was protected because of its political message. The logical extension of this argument is that the harm young children allegedly suffer from being exposed to the word “fuck” is lessened when that term is followed by “the draft” or some similar political statement. Understandably, the Supreme Court in Cohen made no such finding. Rather, the Court considered that unwitting listeners might indeed be exposed to offensive language but nonetheless held that such utterances are “necessary side effects of the broader enduring values which the process of open debate permits us to achieve.” Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15, 24 (1971). Appellee concludes its Response with the statement that Mr. Boomer’s “arguments damage the integrity of the First Amendment.” Appellant’s Response at 24. 4 Perhaps no other statement by Appellee better evidences its misunderstanding of Cohen in which the Supreme Court began its analysis with the statement, “[t]his case may seem at first blush too inconsequential to find its way into our books, but the issue it presents is of no small _______________________________ 4 The impact of this case extends far beyond the prosecution of Mr. Boomer. Since Mr. Boomer's conviction, other Michigan counties have commenced prosecutions for violations of MCL 750.337. For example, the Clare County Prosecutor's Office recently charged a high school assistant volleyball coach with violating the statute for a heated exchange between the school athletic director and the female head volleyball coach. See 2/8/00 misdemeanor complaint in People v. Clevenger, 80th District Court No. 00-0156-SM; see also Mt. Pleasant Morning Sun, 4/17/00, attached as Appendix A. 14 constitutional significance.” 403 U.S. at 15. On numerous occasions, the Supreme Court has stated that for political speech, First Amendment protection is “at its zenith.” See, e.g., Meyer v. Grant, 486 U.S. 414, 425 (1988). If, as Appellee argues, the key to the Court’s analysis in Cohen was the political message of Mr. Cohen’s speech, there would have been no need for the Court’s concern that some might view the case as inconsequential. In fact, the Court specifically states that its decision has nothing to do with the underlying message of Mr. Cohen’s speech. “Appellant’s conviction, then, rests squarely upon his exercise of the ‘freedom of speech’ protected from arbitrary governmental interference by the Constitution and can be justified, if at all, only as a valid regulation of the manner in which he exercised that freedom, not as a permissible prohibition on the substantive message it conveys.” Cohen, 403 U.S. at 19 (emphasis added). The Cohen Court’s statement “one man’s vulgarity is another’s lyric” is one of the most well known statements of First Amendment jurisprudence. But one has to question why the Supreme Court would bother to describe differing emotional responses to the same words if, as Appellee argued and the lower courts accepted, it intended its holding in Cohen to apply only to meaningful expressions of ideas. The lower courts nor Appellee have not provided an answer to that question. This Court should therefore grant Appellant's Application for Leave to Appeal in order to learn the State’s answer. In fact, the answer is provided in Cohen. “[W]e cannot indulge in the facile assumption that one can forbid particular words without also running a substantial risk of suppressing ideas in the process. Indeed, governments might soon seize upon the censorship of particular words as a convenient guise for banning the expression of unpopular views.” Id. 15 at 26. Thus, it was the “risk” of suppressing meaningful ideas, not the actual suppression of those ideas that motivated the Court in Cohen. To eliminate the mere possibility that governments might use the censorship of particular words as a guise for suppressing unpopular views, the Supreme Court has drawn a line in the sand prohibiting the censorship of particular words — whether they convey a meaningful thought or not. CONCLUSION For the foregoing reasons, Amicus Curiae respectfully urges this Court to grant Appellant’s Application for Leave to Appeal. Dated: 4/21/00 Elizabeth A. Cabot (P36677) SACHS, WALDMAN, O'HARE, HELVESTON, BOGAS & McINTOSH, P.C. 1000 Farmer Detroit, MI 48226 313-965-3464 Robert M. O'Neil J. Joshua Wheeler Thomas Jefferson Center for the Protection of Free Expression 400 Peter Jefferson Place Charlottesville, VA 22911 804-295-4784 16 PROOF OF SERVICE The undersigned hereby certifies that true and correct copies of the enclosed Amicus Curiae Brief in Support of Defendant-Appellant's Application for Leave to Appeal were mailed on this 21st day of April, 2000, first-class with postage prepaid, to : Richard E. Vollbach, Jr. Attorney for Appellee Arenac County Prosecutor's Office 120 N. Grove Street P.O. Box 1309 Standish, MI 48658 Michael J. Steinberg Attorney for DefendantAppellant ACLU Fund of Michigan 1249 Washington Blvd. Suite 2910 Detroit, MI 48226 _______________________________ Elizabeth Cabot Counsel for Amicus Curiae 17 APPENDIX A Approved, SCAO STATE OF MICHIGAN th 80 JUDICIAL DISTRICT COMPLAINT Key: 20 MISDEAMOR CASE NO. 00-0156-5m Court Address Court Telephone No. 180025J Court telephone no. : MI- Courthouse, 225 W. Main, Harrison, MI 48625 m THE PEOPLE OF ] The State of Michigan Defendants name and address STEVEN ROBERT CLEVENGER 517 539 7173 Victim of complaint MICHAEL COON V Complaining witness ALLAN WINTERS :o-defendant(s) Date: On or about 1/27/2000 City/twp./Village 9 E. Michigan, Surrey Twp. Police agency report no. SD-00-34-3 County in Michigan Defendant CTN 18-00000115-01 Defendant SID Defendant DOB 10/22/1979 Maximumpenalty See Below Charge See Below Witnesses MICHAEL COON, ALLAN WINTERS, VID BECKEY, GELA ELLEN PAKLLEDINAZ Defendant DLN STATE OF MICHIGAN, COUNTY OF Clare____________________________________. The complaining witness says that on the date and at the location described, the defendant, contrary to law, Count 1 Defendant(s) 01 INDECENT LANGUAGE id;use certain indecent, immoral, obscene, vulgar or insulting language in the presence : hearing of a woman or a child; contrary to MCL 750.337; MSA 28.569. [750.3373] ISDEMEANDOR: 90 Days and/or $100.00 The complaining witness asks that defendant be apprehended and dealt with according to law. (Peace Officers only) 1 declare that the statements above are that to the best of my information, knowledge, and belief. Warrant authorized on February 4, 2000 Complaining witness signature Judge/court clerk/magistrate Cursing lands man in trouble MOUNT PLEASANT MORNING SUN, page 1, April 17., 2000 ~ ByCHRISTY DARG1TZ Cursing Sun Staff Writer (Continued from Page 1) . Based on an 1897 Michigan law, a 20 year-old Mt. Pleasant roar, was charged in Clare County for swearing in front .of a woman. According to Attorney William Street, of Saginaw, Steven Robert Clevenger's use of ob- . scene or vulgar language occurred Jan. 27 during a discussion with the varsity volleyball coach and tbe assistant principal. Clevenger -was fired as Far-veil High. School's assistant volleyball coach after school hours that day, Street saidThe law Clevenger is accused of violating states that it is unlawful to use_ obscene or vulgar language in front of women or children. "Based on the police reports I've seen, I believe this case has nothing to do with using bad language in front of children," Street said. Street said details of the incident will be clarified by the judge and attorneys at the pre-trial April 19.. If convicted, Clevenger could serve up to 90 days in jail , and/or pay a $100 fine, he said… Street, -who represents the American Civil Liberties Union, opposes the law and claims it violates . the Fir$t Amendment. "This law 'was unconstitutional when it was written," he said. The case mimics an incident of a Standish canoeist named Timothy Boomer, who was convicted last June for swearing in front of children. Boomer was canoeing with friends when he fell out of his canoe (See Cursing, Page 2) and into the Rifle River • in 1998. . Street also ' represents Boomer on behalf of the Arneri- . can' Civil Liberties. Union. Boomer is -waiting to hear the .result of his appeal process before he serves his sentence. He was sentenced to pay a $75 fine and work four days in a child-care program, according to associated press reports. In Kalamazoo County and other Michigan counties', the law was declared unconstitutional, Street said.