With another mother tongue

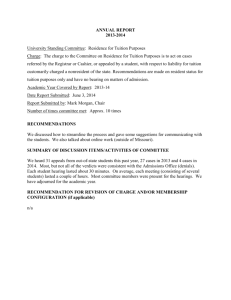

advertisement