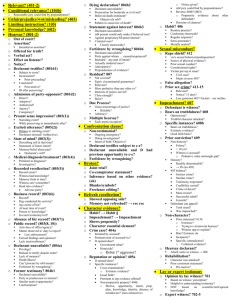

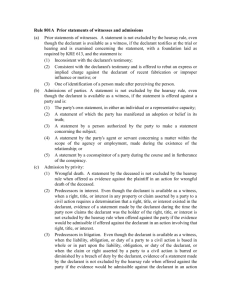

Federal Rule of Evidence 801(d)(1)

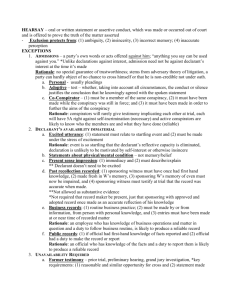

advertisement