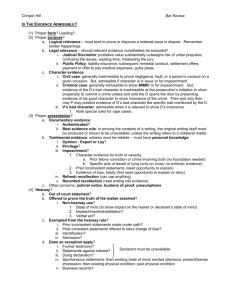

Rule 801(d) Oxymoronic "Not Hearsay

advertisement