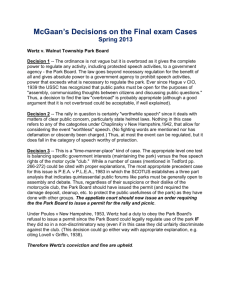

Defamation Law of Wisconsin - Marquette Law Scholarly Commons

advertisement