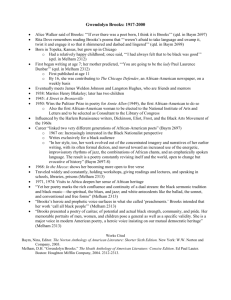

MOTHER UTTERS: STRUGGLE AND SUBVERSION

IN THE WORKS OF GWENDOLYN BROOKS

A Dissertation

Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies and Research

in Partial Fulfillment of the

Requirements for the Degree

Doctor of Philosophy

Kamal Ud Din

Indiana University of Pennsylvania

December 2008

© 2008 by Kamal ud Din

All Rights Reserved

ii

Indiana University of Pennsylvania

School of Graduate Studies and Research

Department of English

We hereby approve the dissertation of

Kamal ud Din

Candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy

______________________

____________________________________

Kenneth Sherwood, Ph.D.

Associate Professor of English, Advisor

____________________________________

Veronica Watson, Ph.D.

Associate Professor of English

____________________________________

Michael T. Williamson, Ph.D.

Associate Professor of English

ACCEPTED

___________________________________ _____________________

Michele S. Schwietz, Ph.D.

Assistant Dean for Research

The School of Graduate Studies and Research

iii

Title: Mother Utters: Struggle and Subversion in the Works of Gwendolyn Brooks

Author: Kamal ud Din

Dissertation Chair: Dr. Kenneth Sherwood

Dissertation Committee Members:

Dr. Veronica Watson

Dr. Michael T. Williamson

“Mother Utters: Struggle and Subversion in the Works of Gwendolyn Brooks”

explores how Brooks uses women's speech and traditional classical poetic forms to

struggle with and subvert the predominant social, moral, and political systems which

impede class mobility and oppress African Americans in general and African American

women in particular. To transform the identity and role of African American women,

Brooks assigns central roles to women, particularly to mothers, in most of her early

works. In this way, she brings them from invisibility to visibility and from objects to

subjects. In order to analyze these works and this phenomenon, particularly, I utilize

Black Feminist theory.

Brooks’s poetry also reflects the fine blending of classical and popular poetic

forms. The tension between aesthetic and politics is one of the prominent features of

Brooks’s works. I explore how she skillfully and artistically transforms classical poetic

forms, such as the sonnet and ballad, and uses them to protest against and destabilize the

preexisting value systems and also how she maintains a delicate balance between

aesthetic and politics in her poems.

In her 1968 volume In the Mecca, we find a shift in her art of narration: The use

of diverse subjects, interior speech and polyvocality in this dramatic poem enable it to

iv

operate on many levels. I investigate what this shift in the narration signifies and how it

effects her poetic and political vision. Maud Martha, Brooks’s sole novel enhances the

themes of resistance and subversion that we find in her first two volumes of poetry. It

also heralds the idea of an essential “sanity.” I also look at Brooks’s works from multisocial and cross-cultural context with the help of Bakhtin’s theory of “dialogism.” I try to

understand Brooks’s women in relation to Pakistani social and cultural contexts and

explore the feasibility of teaching Brooks to Pakistani students at the end of the

dissertation.

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Dedication: To my wife Naveeda and all my children

I am thankful to all my friends in Indiana, Pennsylvania for their moral support and

cooperation, which helped me to finish my doctoral program without any problems. I

shall never forget the initial support and help given to me by Abdul Rahman of Saudi

Arabia. I should thank all the professors who guided and helped me during my stay at

Indiana University of Pennsylvania. I want to thank especially Dr. Susan Gatti and Dr.

Karen Dandurand for their timely help and guidance in every semester. I owe my

gratitude to the staff of Disability Support Services of Indiana University of

Pennsylvania, particularly to Dr. Todd Van Wieren, who has always helped me to get

books from Recordings for the Blind and Dyslexic, to get the books recorded, provided

library assistance, and arranged the recorders for me. I am grateful to the staff of the

Stapleton Library for their cooperation and assistance in finding the books and articles.

I am thankful to Dr. Kenneth Sherwood, my dissertation director whose scholarship and

patient guidance enabled me to accomplish my goal. I am grateful to Dr. Veronica

Watson and Dr. Michael T. Williamson, the members of the dissertation committee,

whose comments and suggestions helped me to look at Gwendloyn Brooks from a new

angle. I am also grateful to all my friends who helped me to maintain my computer and

assisted me in finding online materials. I am obliged to Crystal Hoffman who helped me

as the proofreader; I have no word to thank her for her earnest efforts.

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chapter

Page

I.

INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 1

II.

MOTHER TRANSFORMED: VOICES OF PROTEST

AND SUBVERSION .................................................................................. 29

III. TRADITIONS TRANSFORMED: FORMS OF PROTEST

IN THE EARLY POETRY ......................................................................... 74

IV. DISPERSED NARRATION: SHIFT IN THE MECCA .......................... 115

V.

MAUD MARTHA: AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMAN'S

ATTAINMENT OF VOICE ..................................................................... 159

VI. CONCLUSION ........................................................................................ 189

WORKS CITED ....................................................................................... 198

vii

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

Since I was a young man, I have believed, with no uncertain conviction, that

women are a source of unparalleled strength. Women are and always have been capable

of bringing about change in the lives of individuals, families, entire communities through

the strength of their indomitable will, integrity of character, and moral vision. This is

what I have learned from my eldest sister, who became a widow only three years after her

marriage. My sister was never cowed by unfavorable social and financial circumstances

or by the challenges of a society that looks down upon women as irrational and good for

nothing aside from child rearing and other domestic work. She not only proved what she

was capable of as a woman, but she also educated and trained her two daughters to defy

and resist oppression and injustice with grace and dignity. She had always been a source

of inspiration for me and she has instilled in me the belief that women are not poor,

delicate, weak creatures who must depend on men for their survival. They are also not

destined to walk a few steps behind men; rather they are their equals and can be as good

as men in every area of life, given equal opportunity and freedom to exercise their

potential. The only thing that makes them an “other,” a second class citizen, is the

preexisting system, which evolved through patriarchy and conservatism. Whenever I

think of my sister, I am reminded of the gender oppression, discrimination, and the way

images are imposed upon women.

1

The women of Pakistan, like women of everywhere, have yearned for identities

apart from the ones that have been imposed on them by the values and systems

established by men. For we can hear some stray voices of Muslim women of this region

of the earth, even in the beginning of the twentieth century, asserting their dreams and

aspirations openly, or under a pen name from which it is difficult to determine their

gender identity. However, Pakistani feminist writers are now trying to change the female

identity imposed by social, cultural, religious, tribal, and regional customs and traditions

in an organized way. They are struggling to transform their image and role in Pakistani

society and culture, as well as in the international community. Pakistani feminist writers

have realized that to destabilize the preexisting social and cultural systems that have

reduced them to domestics, nurses of their husbands and children, and invisible members

of the family and society, women must have a voice of their own to articulate their

feelings. They must have the power to assert themselves. The efforts of Pakistani feminist

writers are to establish new identities as dignified, self-confident, and liberated human

beings with the power to articulate themselves and be heard. Now we can hear the voices

suggesting, and even demanding, their equal rights, recognition of their existence, and the

end of gender oppression and discriminatory laws. It is true that some privileged women

in Pakistani society enjoy relative social, political, and economic freedom and civil

rights, but the majority of Pakistani women who are illiterate or poorly educated and

without any regular source of income are still deprived of their rights and denied any

respectable and dignified identity. If Pakistani feminists want to see their dreams of

freedom and respect and empowerment for women in Pakistan, they need to bring the

2

women of the under classes into their folds and include them in their fight against the

gender and class oppression and discrimination.

In reality Pakistani society and culture, have tolerant and flexible dimensions.

They profess and teach their members to respect women and honor their rights, as

defined in the Holy Koran. It has defined in clear terms their basic civic rights as the

members of a society, as mothers, as wives, as sisters, as daughters, and as neighbors.

The prophet of Islam also urges his followers to respect women, treat them kindly, and

give them the rights that are due to them. But, unfortunately these teachings and

education of the Holy Book and school text books are either completely overlooked or

misinterpreted by the so called guardians of society and culture. They highlight the

injunctions of the Holy Book that suit their purpose, and emphasize those verses that

speak of restrictions and prohibitions on women but, play down those verses which give

them permission to acquire knowledge and education, in order to perform their duties as

active members of a society, as well as their role as teachers and nation builders. Feminist

writers in Pakistan are struggling to transform the role and image of Pakistani women.

They are challenging and subverting traditional ideas and value systems, which mostly

belong to regional and tribal social customs and traditions. These primitive and

conservative cultural values are responsible for rendering Pakistani women identitiless

members of the family, as well as the sole property of men. Social, religious, and cultural

norms have defined, in theory, the roles, responsibilities, rights, and obligations of both

men and women. These norms have promised equal opportunity for both sexes.

Theoretically, the laws of the country grant all social, political, legal, and civil rights to

3

women, and they have the right to acquire knowledge, and even have access to higher

education and can adopt the professions of their choice. However, some members of

society, with their preconceived ideas of women - based on male chauvinism, tribal

customs, and patriarchal values- are responsible for depriving women of their rights and

due status.

At present, according to Zamir Badyyuni,Pakistani feminism seems to be

influenced by Anglo-American feminism and French feminism, for Black Feminism is

rarely mentioned. However, Black feminism is a powerful movement and, in my opinion,

is capable of giving new inspiration and vision to Pakistani feminists, who have not

confined themselves to the educated middle classes, but are speaking for the underprivileged, poor, and semi-literate urban and rural women, who are struggling against

gender oppression, as well as caste and class discrimination. Moreover, Black Feminism,

as Alice Walker envisaged, stresses self-determination, appreciation for all aspects of

womanhood, and the commitment to the survival of both men and women. It is meant for

not only African American women, but also women of color, regardless of their race or

region. Alice Walker’s vision of “womanism” urges African American women not to

limit themselves to a specific geographical boundary, but rather link themselves with

humanity at large, especially with women the world over.

Gwendolyn Brooks, the Poet Laureate for the State of Illinois, a teacher, and the

first African American poet to win the Pulitzer Prize, has been a prolific writer. She

wrote and published more than twenty collections of poetry, including A Street in

Bronzeville (1945), Annie Allen (1949), In the Mecca (1968), and a fictional work, Maud

4

Martha (1953), in rapid succession. Her poetry is a subtle blending of traditional forms

such as ballads, sonnets, and popular and folk literary forms like rhythm of the blues and

unrestricted free verse. In short, the popular as well as classical forms of English poetry

are used in her work. Her poetry is characterized by innovation and experimentation as

she juxtaposes lyric, narrative, and dramatic poetic forms. Her lyrics are marked by

affirmation of life despite the social and economic oppression; the subject matter of her

narrative poetry deals with simple stories of common men and women, but it has a

universal appeal; her dramatic poetry is peopled by ordinary characters and it describes

actions that are not heroic. Their struggle to survive in the hostile and inimical world

makes them memorable and their action lofty. Brooks’ works depict African-American

life and culture, and they are bitter and scathing commentary on the impact of social,

political, economic, and racial discrimination, on African American women. They also

give a vivid picture of the social and economic pressures that have stunted their class

mobility as well as the glimpses of African-Americans’ day-to-day existence.

Brooks is not only just a successful American poet of the twentieth Century in

literary terms, but her voice in the struggle for social and racial equality and justice

particularly for African American women is also powerful. She holds the mirror with the

reflection of the world around her, so that others may see the ugly and unpleasant realities

of a ghetto world. Despite the sordid life and tedious questions, the vision and themes of

her poems are not pessimistic. Her themes include the transformation of African

American identity from denigrated to dignified, and the search for happiness despite the

oppressions of racism and poverty. She is a powerful voice for social equality, political

5

justice, and economic mobility for both African American men and women, especially

during the critical times in social and political history, particularly during the days of the

civil rights movement.

I have chosen to apply Black Feminist theory because its professed aims are to

create unity among oppressed and marginalized women, regardless of their class, color,

caste, or creed. This theory also emphasizes women’s need for a voice of their own if

African American women, that is to say, every woman who is facing discrimination and

oppression, are to transform their identity and role in their society. bell hooks, in her

book, Talking Back draws the attention of the reader to this need for “finding a voice” as

“metaphor for self-transformation” (12). Advocates of Black Feminism, like Mae

Henderson, urge black women to acquire expression that will transform them from

individuals being defined to the definers, from objectivity to subjectivity, and from

addressee to speaker.

Black Feminism aims at changing the denigrated images of African American

women and presents them as respectable, confident, and proud women with a solid and

fervent social and political consciousness. It envisages coexistence and cooperation, not

confrontation between sexes. hooks, in her book, Feminism is for Everybody, addresses

men, assuring them that they can also play a positive role in the Black Feminist

movement. She remarks, "’enlightened’ feminists see that men are not the problem, that

the problems are patriarchy, sexism, and male domination” (67). The crux of hooks’ ideas

about Black Feminism is that "feminism is a movement to end sexist oppression" (6). Its

aim is to create awareness of the various factors of oppression and how society idealizes

6

the oppressors and its oppressive values. The Combahee River Collective Statement also

sets forth similar ideas in its statement defining its goals,

The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be

that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual,

heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the

development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that

the major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these

oppressions creates the conditions of our lives. As Black women we see

Black feminism as the logical political movement to combat the manifold

and simultaneous oppressions that all women of color face. (Combahee)

The main aim of Black Feminism may be understood as this: first struggle against

racist and sexist oppression; second, find a black female voice, in order to articulate

aspirations feelings, and grievances; third, empower them to struggle against and subvert

the unjust and oppressive systems without losing their identity and roles as women. Some

African American feminists may disagree with the ideas and purposes of the Combahee

River Collective Statement, Alice Walker’s ideas of Womanism, or bell hooks and Mae

Henderson’s assertion of the necessity of ‘voice, and ‘black female expression’ for the

transformation of African American women’s position and identity in the society, but all

of them agree on one point, that they must struggle against racism, sexism, and color

discrimination.

Most of the feminists in Pakistan are also striving for these same goals, i.e. selfdetermination, admiration and understanding for all aspects of womanhood, and faith in

7

the idea of the survival of both men and women. They don’t want to supersede their male

counterparts; rather Pakistani women want to play their roles side by side with their male

partners as equals, as dignified, respectable, and liberated persons, not as “the other” in

the sense that Simon de Beauvoir has defined it. Tahira Naqvi, the Urdu short story

writer, novelist and translator, points out in one of her lectures that in the beginning of the

twentieth century novels about women and for women were written by men in which they

“mainly stressed the role of ‘good Muslim women,’ how they should behave, how they

should think and talk”. But, according to Naqvi, with Ismat Chughtai, a famous Urdu

novelist, short story writer, and essayist, things began to change, for she wants to see

women through a woman’s eye and narrate their experiences from a woman’s viewpoint.

According to Naqvi, Ismat Chughtai makes Pakistani women writers realize that “it is

possible for women to write like that. It is possible for women to explore. It is important

for women to write about women.” What Naqvi wants to bring home to her audience, in

my opinion, is what Alice Walker has stated in her definition of “Womanism”: the

admiration and understanding of womanhood and giving a voice to women’s feelings

with feminist expression and in a liberated language.

Brooks’ works also gave such messages to African American women in the

1940s-50s with the intention of transforming them from audience to speakers. Her works

reflect all the features of Black Feminism, although she never claims herself to be a

feminist. The study of Brooks’ works, in the context of the salient characteristics of Black

Feminism, could give a new dimension in the understanding of the need for feminist

ideas, particularly black feminist ideas, among female Pakistani readers as well as

8

ordinary readers of poetry written in English. The main feature of Pakistani feminism

according to Kishwar Naheed, the Pakistani feminist poet is the struggle against gender

oppression, class discrimination, and against the restrictions and inhibitions imposed on

women in the name of religion, morality, and decorum. Moreover, they are also trying to

transform imposed identities and destabilize the social and cultural systems that oppress

and exploit Pakistani women. Broadly speaking, we find a number of similarities between

these characteristics of Pakistani feminism and the salient features of the Black

Feminism, so Pakistani students may not find Gwendolyn Brooks’ poetry and her women

characters perfect strangers when they analyze them in the light of the Black Feminism

and in the context of Pakistani feminism. If we could design Brooks’ study carefully and

apply appropriate pedagogy, I think, reading Brooks can teach Pakistani students about

some of the unexplored areas of American life and literature.

As Pakistan was a part of the British Empire till its independence in 1947, it

inherited the education system introduced by its colonial rulers. It continued to follow the

British model, even after it gained its independence, in which English, both language and

literature, was the core subject. The syllabi reflected the teaching of grammar,

composition, and classical British writers at the college level. English was a compulsory

subject and every student had to pass English paper to earn a Bachelor of arts or Science

degree. Moreover the professors, responsible for curriculum and syllabus designing were

mostly graduates from the British universities and they had some bias for British

literature; so they preferred British literature as opposed to American and the literature

written in English from different parts of the world. Hence, it is understandable, why

9

British literature enjoys the central place in the English curriculum of Pakistani

universities. Pakistani students, particularly, at undergraduate and graduate levels, are

quite conversant with spoken and written English. English was taught to the Indians, in

the early days of British rule in the Indo-Pakistan subcontinent in order to produce such

local workers who would become cogs in the British administrative machinery. They

established public schools to create a class that would be loyal to and support the British

government in India. As Tariq Rahman, an educator and prolific writer on place and role

of English in Pakistani society and politics, has pointed out,

The great public schools, like the famous Aitchison College in Lahore,

were based upon the aristocratic model of the English public schools.

Their function was to produce a loyal, Anglicized, elitist Indian who

would understand, sympathize with and support the British Raj in India.

This education system that had laid a great emphasis on teaching English language and

literature subjugated the body and mind of the natives as it imposed the British culture

and value system on them. However, at the end of the day, the knowledge of English

language and literature became a source of awareness and empowerment for the natives

and it was one of the major factors of liberation from colonial rule.

Even today, long after independence, the primary aim of teaching English

literature in the secondary level in Pakistani schools remains to teach the students

language rather than to familiarize them with English literary forms or its aesthetic and

literary qualities. The method that has been used to teach English language is “language

through literature.” In this method the stories, poems, and essays written in English by

10

the local, as well as the British and few American writers, have been taught in the old

translation method. In this method, the emphasis is on vocabulary building, using newly

learned words in sentences, grammar taught through the traditional method of

memorizing rules, and developing the ability to translate ideas from Urdu into English,

and those concepts that they have found in books written in English into Urdu.

One of the purposes of teaching English literature is to develop the ability to

communicate in written and spoken forms, which can help in obtaining a job and give

access to sources of power. According to Rahman, English “is the language of the elitist

domains of power not only in Pakistan but also internationally.” An apparent aim of

introducing and teaching English literature during the British rule was to impose British

culture and ideologies, and to assert the superiority of white men. But after the

independence, the motif and purpose have changed— English literature is taught in order

to teach language, which will enable people to acquire advanced knowledge in the field

of natural sciences, as well as social sciences, and it can serve as lingua franca in

international conferences, while cultural and ideological aspects in the works of literature

are played down.

Pakistani students of the secondary and higher secondary schools are well-versed

in the rules of grammar and have a fairly good treasury of English vocabulary, but are

only familiar with the works of William Wordsworth, R. L. Stevenson, Oscar Wilde, and

some other British and American writers, but they may not have any idea of their literary

merits or their real message and ideas. Their efforts and purposes are to learn the

meanings of the words, to acquire writing skills, and to prepare examination questions

11

which test their memory, not their knowledge. In college, they are introduced to

Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats, Shelley, Hardy, Houghton, and a few American essayists

like Emerson and Twain, short story writers like Hawthorn, O’Henry, and Poe, and poets

like Dickinson and Frost, but again they concentrate on the linguistic and grammatical

aspects of these pieces of literature, rather than on their aesthetic, social, cultural, and

literary features. At this level, also the main emphasis is again on grammar, composition,

and vocabulary building. Students are asked to critically appreciate a poem or a short

story, but they prefer straight questions which have less to do with literary qualities.

Examiners also concentrate on grammar and expression and less on the literariness of the

answers.

In the graduate syllabi of different universities in Pakistan, the main area of study

is British literature, starting from Chaucer to Heaney, from Marlowe to Edward Bond,

from Henry Fielding to Margaret Drabble, and from Bacon to Russell. These universities

allot a small space for American literature in their graduate programs and some short

story writers and poets in undergraduate study. American writers who usually find a place

in the syllabi are Hawthorn, Hemingway, Faulkner, Dickinson, Frost, Wallace Steven,

Arthur Miller, O’Neil, Williams, and Twain. For the last few years, we find names of

some African American writers in the syllabi of some universities, such as Toni

Morrison, Langston Hughes as a short story writer, and Maya Angelou, but African

American literature is largely unfamiliar region for most of our students, as well as many

academics.

12

At this level, the students are encouraged to judge and evaluate the merits of a

work of literature with an Arnoldian yardstick. They do not pay much attention to

intercultural or to multi-social relations or “intermingling of life experience and criticalhistorical judgments” (Frank Rosengarten 82). However, the outlook on the study of

literature is changing, for institutions and systems are coming out of their Victorian

vision of education and ideas of literature, and they are helping their students to look at

these works of literature through post-colonial, feminist, cultural critical lenses. It seems

that those at the helm of the affairs of English departments in Pakistani universities have

realized the need to situate literary works within “the always complex and contradictory

nature of historical reality, and of the specific events and trends that mediate the

relationship between a writer and his time” (Rosengarten 72). Now, they seem to have

realized that in order to properly grasp and evaluate a work of literature, the students, as

well as the teachers, need comprehensive knowledge of social, political, philosophical,

and economic currents of the time when it was created and “emotional as well as

intellectual powers to deal adequately with dense, polysemous texts” (Rosengarten 72).

The vision and philosophy may have undergone certain changes, but the motif of

studying English language and literature remains the same.

Sabiha Mansoor in her article, “Culture and Teaching of English as A Second

Language for Pakistani Students,” has pointed out, the role of English in the education

system of Pakistan, that the students and others in Pakistani society consider English

necessary for social mobility. A graduate in English language and literature has been a

13

respectable person in society and has better access to jobs and power. Tariq Rahman

remarks,

English is still the key for a good future – a future with human dignity if

not public deference; a future with material comfort if not prosperity; a

future with that modicum of security, human rights and recognition which

all human beings desire. So, irrespective of what the state provides,

parents are willing to part with scarce cash to buy their children such a

future. (242)

English is still a popular subject among Pakistani students and their parents for economic,

social, and political reasons. Although it is still taught in old Victorian method in most of

the secondary and higher secondary schools in the countryside and small towns, it is

gradually switching over to the American semester system, at least at the college and

university level, and we also find names of American writers more than ever, since the

inclusion of professors who are the graduates from American universities to the faculty.

With this shift, and other changes in social, political, and economic systems caused by

revolution in computer and information technology, new world order, globalization, and

free market economy, American English and American literature, particularly white

American literature, are gaining popularity among the masses, as well as in the

educational institutions. American accent and style in spoken English and American

spelling and style of expression in writing are gaining popularity among Pakistani

younger generation, especially among the student. However, American literature should

be given a respectable place in the syllabi of Pakistani universities, if Pakistani academic

14

institutions want to teach American literature effectively to their students. It can happen

only if the teachers can help the students to understand American literature from a multicultural perspective and in its social, historical, and political background. No doubt, one

can notice an increase in American titles, yet this is not sufficient. American literature

deserves more extensive and intensive exploration, for what we are imparting and

acquainting the students about American literature is only the tip of the iceberg. Pakistani

students need to know more, if they are to become truly familiar with American life and

culture. Although we find a few American writers in various syllabi of different Pakistani

universities, they have yet to include African American writers, particularly woman

writers, as well as other writers from diverse ethnic communities, so that they may have a

more variegated, as well as a more complete picture of social, political, and economic life

and culture of Americans. By studying the social, cultural, and economic life of

minorities, particularly of women, students may come to realize that these groups are

facing kinds of social, psychological, and emotional problems similar to those that

Pakistanis, particularly women are facing. A writer can be better understood, if we can

relate him or her to the readers own problems and issues. Gwendolyn Brooks can be

taught effectively and understood better if the teachers first introduce and explain to their

students the social, psychological, and political background of African Americans,

beginning with slavery, racial discrimination, the violence that followed Emancipation,

racial segregation, the civil rights movement and the rise of Black Nationalism. Should

this happen, the students will have a vivid insight into the issues and ideas which are

prominent in African American literature, particularly Brooks’ works. The teachers, as

15

well as students, may then properly analyze the problems and issues that are raised in

Brooks’ works in that context and then relate them to their own social, cultural, and

political context.

Gwendolyn Brooks, the Chicagoan poet, interests me for her female characters

and her use of traditional Anglo-American poetic forms to subvert and destabilize

conventional and preconceived ideas and images of African Americans, in general and

African American women, in particular. Brooks’ use of classical forms, with some

modifications, can appeal to Pakistani students, teachers, as well as readers of English

poetry. Pakistani students are accustomed to reading classical poetic forms, such as the

sonnet and ballad forms and they can appreciate the aesthetic qualities and literary merits

associated with them. They are familiar with the development of these forms through the

ages—from Wyatt and Surrey to W. B. Yeats—thus they may be able to appreciate the

changes that Brooks has made in them. Brooks’ use of classical forms to subvert and

destabilize conventional concepts of African American women may not be something

entirely foreign to Pakistani readers, for we also find traditional Urdu poetic forms used

for political purposes since the time of British Raj. Women poets of the second half of the

twentieth century have also used classical, as well as modern Urdu poetic forms to

challenge the traditional concepts of Pakistani women and to voice their resistance and

protest against the social, religious, and gender oppression.

Gwendolyn Brooks is an excellent choice of author to teach African American

literature in Pakistani educational institutions, in particular, for her union of morality and

art. An important criterion for the majority of Pakistani teachers of English literature and

16

syllabus designers is that a work of literature must be moral and didactic, as well as

entertaining. They believe in Matthew Arnold’s idea that “a poetry of revolt against

moral ideas, is a poetry of revolt against life, and a poetry of indifference to moral ideas

is a poetry of indifference to life” (qtd. in Lakshmi). In their article, Patricia H. Lattin and

Vernon E. Lattin have pointed out that Brooks also believe in uniting art and morality for

her creative process. In my opinion; a Pakistani audience will not have any problem in

studying Brooks’ poetry despite the differences in culture, social and moral values, and

psychological and emotional issues. I have found Brooks’ poetry conducive to our social

and cultural values.

The choice of Gwendolyn Brooks for my dissertation has come after a careful

analysis and consideration of her work in the context of social, cultural, and moral

requirements of my own society and those of the academic institutions in my country. I

was introduced to Brooks with a beautiful and haunting poem with nursery rhyme

rhythm, “We Real Cool”:

We real cool.

We Left school. We

Lurk late. We Strike straight. We

Sing sin. We Thin gin. We

Jazz June. We Die soon. (Black 331)

The precarious conditions, uncertainties in life of these players, and maternal concerns

and worries of the poem, as well as its unusual form of prosody induced me to read her

collection, The Selected Poems.

17

While browsing through the collection, I became interested in its female

characters, because of their independent minds and their moral and mental courage to

destabilize and challenge unjust and discriminatory systems. Brooks’ women and

mothers’ struggle is to subvert oppressive systems and to transform the denigrated images

of African American women into respectable and dignified ones. Their effort is to evolve

an “alternative system” (Erkkila 200) in which African American women will have

independent identity of their own as ‘makers’ and an existence visible to others. These

characteristics of Brooks’ women made me feel that they could help me to look at the

women and mothers in my society from a new angle and add a new voice to the efforts of

Pakistani feminist writers who are struggling to subvert and destabilize preexisting

identity and ideas. I understand the actions, reactions, and utterances of Brooks’ women,

particularly the mothers, as the resistance, protest, and subversion against oppression,

discrimination, and injustice. They represent their individual struggles and subversion as

well as a broader spectrum of the African American woman’s efforts to destabilize the

preexisting identity and ideas. If we look at Brooks’ women and mothers as the different

facets of a picture, we can understand that Brooks is creating the image and identity of a

new African American woman. From this perspective, I trace their progress from silent or

internalized resistance to verbal articulation of anger and resentment a transition from

lack of articulation to the attainment of voice. This achievement is essential to the

change in their identity and status in the society. The attainment of voice is followed by

the development of their consciousness from personal to communal, as well as its

transference to the majority community by widening its scope. Brooks’ women are

18

conscious of social and political injustice, racial and color discrimination, and their

identity in the society, but it is initially a consciousness limited to an individual or a part

of the community. However, as Brooks’ poetic career progress, the consciousness in her

women also broadens. Ultimately it penetrates into the consciousness of majority

community, and makes them realize their oppression, injustice, and atrocities. Brooks’

women and particularly the mothers extend their anger and awareness of sufferings and

injustice to the oppressor and thus make them their partners in their struggle against the

race oppression and male supremacism.

Pakistani woman readers may appreciate Brooks’ poetry better, as compared to

men, because of the parallel features in their problems and situation. If Pakistani women

are given proper insight into the nature of social, gender, and economic oppression that

the underclass of African American women have to confront, it will help them to

comprehend the importance and necessity of their struggle against and subversion of their

given identity and preexisting systems. In this way, they will be able to look at their

struggle in a multi-social and inter-cultural context. This broader vision can give new

momentum to their protest and resistance against sexist and religious oppression and

class discrimination.

To achieve insight into Brooks’ ideas in her works and the significance of the

transformation of the image and roles of African American women, as well as to attain a

broader vision of feminist struggle, both the teacher and student will have to recognize

the importance of the relation between literature and social, cultural, and political

conditions in which that work of literature is created, and they should be able to

19

understand and link it with their own social, cultural, political problems and issues. In

this way, Pakistani students will be able to appreciate the way Brooks treats cultural

diversity and mediates between predominant values and newly evolved values in her own

society. Pakistani woman writers can also strengthen their struggle to negotiate between

traditional concepts of women who were not allowed to think and express independently

and the new image of free and self-conscious women, who can express and assert their

identity and individuality in bold and liberated language without any inhibition.

The problems that Brooks’ female characters face may not be exactly similar to

those that Pakistani women have to face but if we try to understand and look at them

from broader perspective, we can realize that they are facing almost the same challenges.

The issues that Brooks brings up through her women are basic psychological, emotional,

social and economic problems that ordinary under privileged individuals, including

African American men and women have to face. Their sufferings, oppressions, and

injustices committed against them constitute the themes of her works. Brooks’

sympathies are for the underclass of poor neighborhoods, particularly, for poor old men

and women, poor and starving children, the youth who are the victims of violence

committed by both whites and blacks, and, particularly, poor and oppressed mothers. The

issues and problems that Brooks takes up in her poetry are the basic issues and problems

that are being faced by poor, oppressed, and looked down upon persons in any society

any where in the world. My effort, as an academic, is to introduce Brooks’ works to the

students of my institution and make them aware of the struggle of African American

women to resist and destabilize preexisting systems and overcome oppression and

20

injustice in society. My attempt is to make them realize that despite the differences in

social and cultural systems, there are still common denominators of oppression, injustice,

and gender discrimination.

In Pakistani society, women are treated as inferior beings, as compared to men,

and the oppression of women is a common phenomenon. Pakistani feminist writers are

trying to challenge and subvert the ideas and systems that enable men to impose the

identity that enhances their superiority on women, oppress them and commit violence

against them. In this context, Brooks’ voice of struggle and subversion can invigorate the

efforts of young feminists and students who are trying to challenge the religious

orthodoxy, male chauvinism, and class discrimination, for she represents under classes

and discriminated sections of American society. Her voice is, therefore, more authentic

than that of the white feminists who represent the privileged middle classes.

Brooks, in her works, situates her women in such circumstances and conditions

that the society, as well as its victims, may realize the afflictions and oppressions that

these underclass women are undergoing. Brooks portrays so called “bad women” in such

a way that their humanity is brought out very clearly. They are not given any image

except the image of human beings, with all humanity’s vices and virtues, weaknesses and

strengths. They are neither flawless angelic figures, nor unredeemable sinners; they are

presented as human beings of flesh and blood. They are women with sensitive souls and

womanly passions. Some Urdu writers in Pakistan have created such women who,

according to social and moral criteria, may be condemned as bad women, but they still

retain their humanity and human values. Such women in Brooks’ poetry, and in the

21

writings of Pakistani women writers, can form a common criterion to understand

common issues that they have to face in their day to day existences.

To understand foreign literature, one should be able to create some links between

the literature that one is reading and one’s own social, political, and cultural context. In

his article, “Teaching African-American Literature in Turkey: The Politics of Pedagogy,”

E. Lale Demirturk points out how he tries to create meanings for the Turkish students

while he was teaching African American literature by using different examples from

diverse cultural context and making his students realize how oppressors constructed

meaning of the words according to their own visions and interests. According to

Demirturk, to understand the words in new light and construct a new meaning according

to one’s context, one needs to shift "a location of privilege" (hooks, Teaching

Community 99). With this shift in the “location of privilege” a new understanding and

meaning will dawn on the readers. This new outlook will enable them to relocate the

position of the previously colonized and enslaved classes, as well as African-Americans

and also able to shift the paradigm Myung Ja Kim in her article, “Literature as

Engagement: Teaching African American Literature to Korean Students.” also discusses

cultural, economic, social, and political implications regarding Koreans' perception of

and attitudes toward African Americans, especially after the Los Angeles riots of 1992

while teaching African American literature to Korean students. She also stresses the need

for the ability among the teachers as well as the students to come out of the constructed

meaning imposed by the media and predominant class, concerning African Americans,

and the ability to reconstruct a new meaning and image in their social, political, and

22

cultural context based on new paradigms, reconfigured in the light of new knowledge and

information.

While I am trying to understand Brooks’ poetry, the narrator’s voice, and the

utterances of the characters, I realize that the meaning that I am giving to the utterance

and words, may not be the same as an African American or an American may understand

it. The meaning of the words and language may have changed according to the social,

cultural, and the value systems in which I have been brought up and lived. No doubt, I try

to interpret and understand in the context of American and African American social and

cultural perspective, but original learning and grooming prompt a different perspective

that may vary significantly from that of Brooks’ culture and ideas. It is not only the

matter of social and cultural background, but as an individual, my understanding of an

utterance or even a single word may differ from that of the poet or other readers.

According to Bakhtin,

The word in language is half someone else's. It becomes "one's own" only when

the speaker populates it with his own intention, his own accent, when he

appropriates the word, adapting it to his own semantic and expressive intention.

Prior to this moment of appropriation, the word does not exist in a neutral and

impersonal language . . . but rather it exists in other people's mouths, in other

people's contexts, serving other people's intentions: it is from there that one must

take the word, and make it one's own . . . Language is not a neutral medium that

passes freely and easily into the private property of the speaker's intentions; it is

populated -- overpopulated with the intentions of others. Expropriating it, forcing

23

it to submit to one's own intentions and accents, is a difficult and complicated

process. (Pam Morris 77)

It is natural that when I read Brooks’ words or utterances, I will assign my own

meanings or interpretations to them to make it my “property” and only then will I

transmit it to my audience. I may mold them according to my comprehension, which is

influenced by my social and cultural perspective, as well as my education. However, my

initial effort is to understand the meanings of the words and utterances in the social,

cultural, literary, and political context in which Brooks utters them. My meanings and

interpretations will be colored by my individuality, my culture, and my value systems.

My audience, in turn, will assign them their own meanings and understand them in their

own context. The process of constructing meaning starts when the readers read Brooks’

words and utterances and when they first try to understand them, keeping in view the

social, cultural, and political perspective in which they are uttered, then their social and

cultural training prompts them to look at them from their own perspective. In this way,

my, as well as their, meanings intersect with authoritative meaning and it creates a new

interpretation and new dimension in the understanding of the text. The new interpretation

and understanding are based on the intersection of two culture and two ideologies. In this

way, we are looking at Brooks works from an angle that American readers may overlook

or may fail to notice.

In this world that has shrunken to a computer screen, the interaction and struggle

among diverse consciousnesses and languages are creating new understandings and new

levels of meanings. Bakhtin remarks, “However, it is in this struggle with another's word

24

that a new word is generated. The dialogic relations of heteroglossia do ensure that

meaning remains in process, unfinalizable” (Morris 74). Gwendolyn Brooks is an African

American poet and has written her poems under specific social, political, and cultural

conditions, but we can not limit the utterances in her works to the meanings that suit one

particular community. Every individual and community can look at them from their own

social and cultural perspective and understand it according to their own consciousnesses.

In this way, Brooks’ works assume a broader scope and a wider audience that multiply

layers of meaning to her words and utterances. In fact, with expanding readership,

Brooks’ works become multi-cultural and multi-national literature. They have

transcended the limits of African American social and cultural environment and can be

looked at and understood from other social and cultural perspective. Bakhtin states

The living utterance, having taken meaning and shape at a particular

historical moment in a socially specific environment, cannot fail to brush

rip against thousands of living dialogic threads, woven by socioideological consciousness around the given object of an utterance, it

cannot fail to become an active participant in social dialogue.”(Morris 76)

With an adequate introduction of social, political, and psychological perspective,

Pakistani students, particularly, female students will be able to appreciate Brooks’ ideas

and message. Although they are primarily meant for African American women, they can

be related to every woman who is living in an oppressive system and facing sexual

exploitation, and gender discrimination. Pakistani women can identify social, emotional,

psychological problems of African American women and look at them in their social and

25

psychological context, for both the communities are facing problems of identity,

recognition as respectable human beings, gender and class oppressions.

Keeping in view Bakhtin’ ideas and the salient features of the Black Feminism, I

explore Brooks’ early poetry. My stance is, through female characters, particularly

mothers and their utterances, Brooks tries to destabilize the preexisting identity of

African American women and the systems that oppress and make them invisible. In the

second chapter, I study how she uses women, particularly mothers, to transform the role

and image of African American women from denigrated creatures to self-defined and

conscious human beings, who are sensitive to their role as teachers, leaders, and nurturers

of new women with refined ways of thinking and vision. I explore these various changes

in the roles and images of African American women. I also highlight the progress of

Brooks’ ideas as an artist through these various roles that African American women play

under different circumstances and on different occasions. My aim is to highlight the

central place that Brooks gives to her woman and how she changes their position from

objectivity to subjectivity; and from ’make’ to ‘maker.’

In the third chapter, I analyze Brooks’ use of classical poetic forms to voice the

struggle and subversion on the part of poor African American women to destabilize

received identities and preconceived ideas. I discuss Brooks’ choice of the sonnet and

ballad forms and the transformation that she makes in them, in order to serve her purpose

of subverting and destabilizing the prevalent ideas and systems. In this chapter, I analyze

Brooks’ use of parody and the anti-hero to destabilize the traditional identity of African

American women and to subvert the preexisting ideas of African American womanhood.

26

Chapter four studies shift in her narrative technique. “In the Mecca,” her longest poem,

she gives up the cloak of situated language and directly addresses the poem to AfricanAmericans. The narrator and Mrs. Sallie Smith guide us through the Mecca building and

tell, as well as show, us the miseries and poverty of the under-classes of African

American society. They along with Pepita give the vision of liberation and collapse of the

Mecca building, the symbol of confinement and constrictions. The fifth chapter looks at

Brooks’ only novel, Maud Martha in which she gives the vision of new African

American woman, who is trying to establish her identity and carved her place and role in

race, color, and gender biased society. She defies and resists race and color

discrimination with dignity and grace. Despite unfavorable conditions and ugliness in the

society, she optimistically looks at the unpleasant aspects of life. The message of the

novel is “bon voyage.” The novel ends with an optimistic note and a call for sanity. At

the end of the dissertation and in the sixth chapter, I discuss how Brooks’ work is suitable

to teach to Pakistani students in Pakistani colleges and universities.

The poems that I have analyzed in the second chapter mostly deal with the image

and role of African American women and the social, economic, moral, psychological, and

emotional problems that make them invisible and thwart their imaginations and dreams. I

have selected these poems to demonstrate the progress of consciousness in Brooks’

women characters, particularly, the mothers. These poems unravel the different roles that

African American women and mothers play in the society. Their progress indicates the

progress in Brooks’ poetic career and the maturity of her thought. The poems in the third

chapter give insight into the changes that Brooks has brought about in her use of classical

27

poetic forms and her innovations in them. I have selected these poems for they help me to

show how Brooks adopts parodic voice and the figure of the anti-hero to subvert received

identity and concepts. I have selected “In the Mecca” to show that despite the impression

that her poetry after 1967 has lost her earlier aesthetic qualities and has become more

political, she still continues with her earlier themes and aesthetic vision as well as her use

of women and mothers to destabilize and reconfigure a new system based on “essential

sanity black and electric.” My emphasis is that the shift in her poetry occurs at the levels

of narrative style, which has become dispersed, and more complex, and language, which

has become more direct as compared to her early poems. Although it was written in 1953,

I discuss Brooks’ sole novel, Maud Martha in the fifth and last chapter, because of its

genre. I try to show that its themes and the vision that Brooks put forth in this novel are a

continuation of the preceding works and are taken up in later books. It is an essential part

of Brooks’ development as an artist. My effort in this dissertation is to demonstrate that

the mothers and women in Brooks’ works are different facets of a complete image. In

other words, they are different phases of growth and progress of the mother character,

which in turn gives insight into the progress in Brooks’ social and political roles, as well

as her development as an artist.

28

CHAPTER II

MOTHER TRANSFORMED: VOICES OF PROTEST AND SUBVERSION

Gwendolyn Brooks transforms the traditional image of the African-American

woman from that of a sexual object and takes them out of their general state of

invisibility in order for them to become independent and self-confident women with

individual voices, She uses them to voice protests against racial, gender, and color

discrimination, to struggle against oppression and injustice, and to subvert the

predominant culture and systems that have rendered them void of both soul and identity.

Her works are peopled by images of suffering and the oppressed black women of

Bronzeville, who represent the down and out of the nation’s black neighborhoods.

Brooks’ sexual as well as racial identity and her experiences in a Chicago ghetto have

enabled her to look at urban experience of black women with a new vision.

Brooks' poetic work may be read as an effort to promote the emergence of black,

female subjectivity and an attempt to articulate and highlight the unarticulated and

unrecognized place and role of the black woman, and particularly the black mother, in the

culture and society that does not recognize her identity and, sometimes, even her

existence. Ann Ducille in her book draws our attention to this attitude of both white men

and women while referring to Sojourner Truth’s famous speech “Ain’t I a woman?”: she

remarks, “Truth’s words were actually a scathing indictment of the racist ideology that

positioned black females outside the category of woman and human while at the same

time exploiting their ‘femaleness’"(36). In most of her early poems, Brooks makes poor

29

black women subjects, for she knows that, as Paulo Freire has put it, "They cannot enter

the struggle as objects in order to later become human beings” (68). The oppressors have

stereotyped the oppressed in such a way that the oppressed have been transformed, either

as non-persons or inanimate or invisible objects. If they want to become human beings

with dynamic identities, not as stereotypes, they will have to struggle as subjects not as

objects. Brooks transforms them into subjects and gives them voices to articulate their

emotions, feelings and problems: Thus she makes them visible human beings with

individual identities. She assigns the central roles to female characters and gives them

what Mae G. Henderson calls “black and female expression” (Cheryl A. Wall 24). With

this voice and expression, her characters forcefully speak against the indignities and

discrimination committed against African-American women in a racist and sexist society.

Her women are transformed women who have attained the awareness of their identity and

voice to articulate their anger and resentment against social and gender injustice. They

are also conscious of their place and role in the changing social and political scenarios.

The introduction of Brooks in syllabi of Pakistani universities, can give new

impetus to Pakistani women students who aspire to change the image and role of women

in Pakistani society. They are trying to challenge the identity imposed by their sexist and

gender oppressive society. The study of Brooks’ women’s efforts to transform their

preexisting identity and values in the frame of the Black feminist theory can be helpful to

Pakistani women who have been expressing the urgency of the need for transforming the

image and role of Pakistani women since the early half of the twentieth century when the

term feminism was not yet in vogue. In those days, according to Naqvi, the concept of

30

“truly liberated women,” or what we later called feminists, was gaining roots among

Pakistani women’s writing through the works of Ismat Chughtai. Through works like

these, Pakistani women have realized the importance of changing one’s identity, as well

as one’s role in society, in order to assert one’s existence and to destabilize the oppressive

measures applied by patriarchy. They believe that what is needed is an agency to voice

their anger, resentment, and protest and that agency is literature written by Pakistani

women themselves.

The Peshawar correspondent of the daily “Dawn” of June 20th, 2008, in his report

on a discussion on the “Portrayal of women in Literature” Organized by the Aurat

(Woman) Foundation, quotes Atiya Hidayatullah, president of the Women Writers'

Forum, who has pointed out in her speech during a discussion: "There is a need to stop

portraying women as a downtrodden section of society in literature. The stereotypical

characterization of oppressed women in literature should be replaced with a more aware

character, fighting for her social rights." We can hear the same kind of arguments and

voices in Gwendolyn Brooks and among the Black Feminists as well. Brooks tries to give

new identities to her women by giving them voice, which enables them to subvert and

destabilize the ideas and values that subordinate them to men. The Black Feminists in the

1970s-80s also stressed the attainment of voice and expression in the pursuit of

transformation from objectivity to subjectivity. Pakistani women writers, like the Black

Feminists, realize that to transform their image and role, they must struggle to attain the

voice of their own.

31

As Naqvi has pointed out, Pakistani women should not rely on men writing about

women, but should themselves be writing about their lives and their feelings. Pakistani

women writers know the significance of the ability to define their image, role, and

feelings by themselves, for if they are described by men, they (men) will impose ideas

and identity that are in conformity with their preconceived ideas and pictures of women.

Pakistani women are aware that the change must come from within, not from old systems

that have defined women as docile and fear-bound creatures. They understand that the

tales of their woes, sufferings, and oppression are not enough to transform their lot. They

should make a stand for their rights in their writings. What they need is to create

understanding among the majority of the members of their society to appreciate their

stance and make them accept their new identity, as well as new roles in the society.

Brooks is also trying to make her society understand the social, psychological, emotional,

and financial problems of African American women and their image and identity.

Brooks’ moral vision, artistic skill, and her ability to negotiate between authoritative

discourse and internally persuasive discourse may enhance the Pakistani women’s

struggle. It will not be difficult for them to assimilate her ideas and tactics to destabilize

the preexisting social and moral systems in their struggle.

A prominent feature of Brooks’ poetry and her novel is the changing role of black

women from addresses to speakers, or from someone who is described by others to

someone who speaks for herself, about herself, and by herself. This change of role from

objectivity to subjectivity or makers from makes allows them to play significant roles, in

32

order to aspire for social and economic mobility, and to figure prominently in the moral,

social, economic, and political life of their community.

Brooks’ treatment of women differs from that of her senior contemporaries, such

as Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison, who also set their writing in an urban environment,

in that she spotlights the experiences of impoverished urban women in her works. In A

Street In Bronzeville (1945), Annie Allen (1949), and The Bean Eaters (1960), her first

three books of poems, her female characters, mothers, in particular, are the central

characters. While there is no doubt that Wright and Ellison assign certain roles to the

women characters in their works, they are not the main players of the plot, rather they are

background figures or play second fiddle in their urban world. But Brooks, in her works,

concentrates her attention on the effects of the “urban experience” on both AfricanAmerican men and women, highlighting that of the female characters and assigning to

them the most pivotal roles in order to expose the impact of urban experiences on social,

moral, and emotional life of women.

Brooks’ work is marked by powerful and strong female characters that play the

main roles in their families, as well as in their societies. Their most prominent role is that

of warriors in the battle against inequality and injustice in society. They are women with

strong wills who do not submit to the unfavorable odds in their lives and fight against

exploitation and injustice of all kinds. Gwendolyn Brooks’ female characters, especially

mothers, differ from traditional female characters in this respect: Brooks’ characters are

unyielding, rebellious, and non-conformist, while the traditional concept of “good

womanhood”, as described by Ajuan Maria Mance in her book, Inventing Black Women,

33

is that of a woman that is humble, submissive, and that accepting of social norms that

have been laid down by patriarchy. Brooks situates women in notably commanding

positions. In her works, they are no longer invisible or identitiless figures, fallen beings,

and sex symbols, rather, they are morally, emotionally, psychologically strong and

powerful characters who struggle and fight against those values and norms that choke

their imaginations, crush their dreams, and relegate them to back seats.

Brooks’ women expose the unpleasant and undesirable aspects of their society.

Brooks’ women hold up a mirror to society which reflects its follies and foibles, evils and

vices, cruelties and injustices. Their speeches and utterances subvert and destabilize the

predominant systems so that they may reconfigure new ones, which will be conducive to

their aspirations and ambitions. Brooks’ women expose ugly aspects of society, but do

not fret and fume against them; rather, they touch the conscience and consciousness of

the readers by pointing out the tragedies, sufferings, and miseries of poor AfricanAmerican women. In this way, she gets their voices of agony, anguish, and resentment

heard and their abject lives visible. Brooks uses her characters to uncover the vices and

weaknesses in her society and satirizes them without resorting to cynicism and violence.

Her characters do not tell us that there are evil and vices, such as, injustice, oppression,

corruption, or racism; rather, they point out the tragic conditions in which they exist and

its relationship to individuals in hopes, that we may learn a moral insight from the

juxtaposition of beauty and ugliness, death in life, and romance and reality. Brooks, in

her works, transforms not only the roles of African American women from objects to

subjects and from addressees to speakers, but also their stereotyped images—from

34

denigrated portraits to dignified ones, and from sex objects to strong and powerful

women with social, moral, and political visions. It is something unusual for African

American literature of the first half of the twentieth century to depict African American

woman as self-defined and self-respecting figures, because the male writers of this

period, as Emily J. Orlando has pointed out in her essay “Feminine Calibans” and “Dark

Madonnas of the Grave” portrayed women as “objects d’ art and beautiful corpses—

sometimes both at once – reducing them to objects of their Gaze,” and also as “feminine

Caliban” (Tarver and Barnes 65). They also present women as small in physical and

mental stature in order to give the impression of them being disempowered beings.

Another image assigned to black women in those days was that of a depraved and

licentious woman who yields to her every sexual desire. Gwendolyn Brooks in her works

tries to mitigate the damage done to African-American women by such images which

promote them as inanimate objects, vile semi-human beings, and creatures of

unrestrained and uncontrolled sexual desires. She tries to transform their image by

rendering her female characters dignity, respectability, and power. She presents them as

mentally and morally strong figures. Some of her women are prostitutes, like Mame in

“Queen of the Blue,” but they have self-respect and rebellious natures that save them

from being viewed as completely fallen beings; or powerful and determined women like

Mrs. Booker T, a poor mother, who can overcome a mother’s love for her son and breaks

her maternal bond when he violates her moral values.

Brooks’ works reveal diverse roles and images of African American women.

Their primary role is that of the makers, who are struggling to reconfigure a social,

35

political, and moral system in which their social and economic mobility is possible. We

observe Brooks’ gradual “unmasking” of the progression in the mother’s social and

political roles, as well as the transformation of the image of women in her poetry. Most of

Brooks’ early poems are studies of the complex psychological and emotional problems of

black women, particularly that of mothers. She probes into their psychology as they try to

adjust their lives according to the gloomy and unfavorable conditions of the kitchenette

building, where their “dreams” of social and economic mobility are frustrated by “onion

fumes" and "yesterday's garbage ripening in the hall” (Black 20). In the wider social and

political life of racist America, their hopes and aspirations are smothered by the traumas

of the lynching of their lovers and sons and the hostility of race and color prejudice—so

much so that their faith in America is weakened by the racial discrimination they face

even when they defend America in Patriotic Military service. In the sonnet, “the white

troops had their orders but the Negroes looked like men” in the sonnet sequence, ”Gay

Chaps At the Bars,” brooks is careful to note that the different boxes are assigned for

dead bodies of black and white soldiers: "a box for dark men and a box for Other” (Black

70).

Brooks uses African American women and mothers to expose the multifarious

problems being faced by urban slum dwellers and through their utterances she points out

sources and causes of their abject poverty and deplorable social conditions. In this way,

she creates consciousness in the society of prevailing inequalities and injustices, in hopes

that this awareness could help to rectify the follies and vices of society. On the other

hand, it might also create desire for economic mobility among African American men

36

and women that will enhance their social and class mobility. In most of her poems, her

canvas is limited to a small kitchenette apartment or a room in a club or a bar, but her

themes and the subject matters are universal, as they deal with basic human problems.

“Kitchenette Building,” which Brooks described as typical of the bulk of her work, deals

with the basic problem being faced by poor and deprived persons—the frustration of their

dreams of amelioration of social and economic conditions and class mobility. The poem

narrates the socio-economic, psychological, and emotional problems of the inhabitants of

the sordid, squalid, and enclosed structure which resembles a trap, and who are

preoccupied with day-to-day survival and have to give up their dreams or “imagination”

and attend to urgent practical needs. Brooks employs a housewife, probably a mother, to

voice the unfulfilled aspirations, unaccomplished ambitions, unrealized imaginations, and

“dream deferred” (Langston Hughes 426).

The narrator's voice is a collective voice, instead of the first person singular, ‘I’,

she uses the plural ‘we’: “WE ARE things of dry hours and the involuntary plan, /

Grayed in, and gray,” (Black 20). The men and women living in this entrapped place are

not human beings, they are inanimate objects, and “things of dry hours” (Black), and in

such a dreary and oppressive atmosphere dreams have a very slim chance of survival. For

those who are struggling for day to day survival, their hopes and imaginations are choked

by financial stringencies: "‘Dream’ makes a giddy sound, not a strong one like ‘rent,’

‘feeding a wife,’ and ‘satisfying a man’” (Black). According to the narrator, even if the

inhabitants of the kitchenette building could keep their dreams clean, warm, and alive, the

other practical problems and necessities of life will not allow the characters to cherish

37

them. The final lines describe how their dreams vanish into the thin air: “. . . . let it begin?

We wonder. But not well! not for a minute! Since Number Five is out of the bathroom

now, We think of lukewarm water, hope to get in it” (Black). The overtone of this line is

both comic and pathetic. For an insensitive reader, the action may be seen as comic, for,

the apparent, incongruity between the serious matters that are discussed in the preceding

lines and the frivolity of the action being described in this line. Brooks uses Bathos, the

sudden change from a serious subject or feeling to something that is silly, or not

important or banal to create comic moments in her poetry. But for a reader who can feel

the deprivations and poverty of ghetto dwellers dream of “lukewarm water,” this symbol

of physical comfort and improved economic conditions, is thwarted by capitalistic and

racist systems. Moreover, as Hansell has described, it gives a more definite sense of what

was implied in the opening line. In this poem, the narrator is a commentator who is

drawing the readers’ attention to the need for an alternative system that may help poor

African Americans to fulfill their dreams. At the same time she is exposing social

problems, economic hardship, and emotional frustrations that are destroying the

yearnings of the poor inhabitants of the kitchenette building.

Brooks’ women are neither heroic nor god-like in attributes or stature; they are

average human beings with typical human weaknesses, who are fighting against their fate

bravely, yet with resignation. She portrays her characters lovingly, realistically, and

objectively. She does not condemn any character for his/her follies, foibles, or vices, nor

extol any character for his/her race, color, sex, or morality. Rather, she treats both good

and bad characters equally regardless of their vices or virtues, social or economic

38

condition, and race. She loves every one of her characters for only one quality, that he

/she is a human being. Norris B. Clark in her article “Gwendolyn Brooks and a Black

Aesthetic,” remarks,

Brooks' poetry remains one of love and affirmation, one that accepts some

hate and perhaps some violence as necessary without condemning or those

who have been pawns to interracial and intraracial forces. Adequately

reflecting the hopes and aspirations of the black community, Brooks

displays a love for her brothers and sisters regardless of psychosocial or

socioeconomic position. (Mootry and Smith 92)