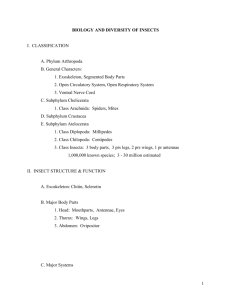

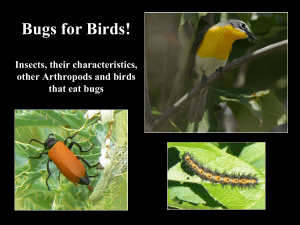

Insects Binder

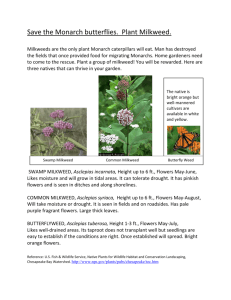

advertisement