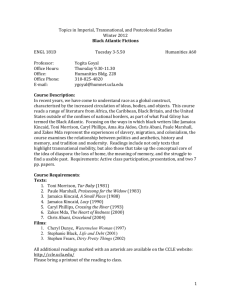

1 chaos, loss, passage and desire. the experience of diaspora in the

advertisement