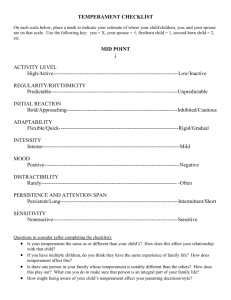

CHILD TEMPERAMENT AND PARENTING

advertisement