Prof. Feibelman (Spring 2006)

advertisement

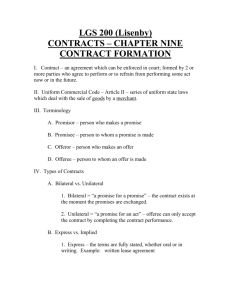

CONTRACTS I. The Contract—requires both mutual assent and consideration. R 2d §17— K=MA + C. Will not enforce gifts (no consideration) a. Congregation Kadimah Toras-Moshe v. DeLeo—man promised to give 25K to congregation but died intestate without delivery of money. II. Was there Mutual Assent? (Meeting of the Minds, Intent to be Bound) a. Standard for determining meaning is objective—RPP would believe there was an offer. i. Embry v. Hargadine, McKittrick Dry Goods Co.—employment dispute over whether employee had contract for another year. The standard for mutual assent is objective—if RPP would think k formed then it was. Intent of offeror does not matter. b. Disputes often arise over whether there was mutual assent— i. Kabil Development Corp. v. Mignot—dispute over whether contract for helicopter services was formed or not because safety inspection failed. Must look at all of the evidence—including the impressions of the parties. ii. Joseph Martin Deli v. Schumacher—dispute over terms of rental agreement and price for extended contract. When terms are vague then not enforceable, look to prior business dealings, court may be able to provide remedy to dispute. c. Certainty and continuing negotiations— i. U.C.C. §2-305—if parties so intend, they can conclude a contract for sale even though the price is not settled. In such a case, the price is a reasonable price at the time for delivery if: 1. Nothing is said as to the price, or 2. The price is left to be agreed by the parties and if they fail to agree, or 3. The price is to be fixed in terms of some agreed market or other standard as set or recorded by a third person or agency and it is not so set or recorded. ii. R 2d §33—Certainty 1. Even though a manifestation of intention is intended to be understood as an offer, it cannot be accepted so as to form a contract unless the terms are reasonably certain. 2. The terms are reasonably certain if they provide a basis for determining the existence of a breach for giving the appropriate remedy. 3. The fact that one or more terms of a proposed bargain are left open or uncertain may show that a manifestation of intention is not intended to be understood as an offer or acceptance. iii. Empro Mfg. Co. v. Ball-Co. Mfg. Inc.—Empro showed interest in purchase and sent letter indicating desire to purchase. Purchase 1 iv. v. vi. vii. terms set, subject to conditions, conflict over one of terms. Ball started negotiations with someone else. Empro was not bound so no enforcement of deal. R 2d §20— 1. There is no manifestation of mutual assent to an exchange if parties attach materially different meanings to their manifestations and a. Neither party knows or has reason to know the meaning attached by the other, or b. Each party knows or each party has reason to know the meaning attached by the other. 2. The manifestations of the parties are operative in accordance with the meaning attached to them by one of the parties, if a. That party does not know of any different meaning attached by the other, and the other knows the meaning attached by the first party; or b. That party has no reason to know of any different meaning attached by the other and the other, and the other has reason to know the meaning attached by the first party. Raffles v. Wichelhaus—two Peerless ships, confusion as to which one was meant. No contract because no meeting of minds. Flower City Painting v. Gumina Const. Co—confusion as to what was to be painted (inside/outside/both). No contract because was not clear from terms. Dickey v. Hurd—offer to buy land, given deadline, confusion if this was date of acceptance or date $ due. Burden on seller to make terms clear so deal must continue since buyer assented to deal before deadline. 2 III. OFFERS a. Was there an offer? i. R 2d §24—an offer is the manifestation of willingness to enter into a bargain, so made as to justify another person in understanding that his assent to the bargain is invited and will conclude it. ii. R 2d §26—A manifestation of willingness to enter into a bargain is not an offer if the person to whom it is addressed knows or has reason to know that the person making it does not intend to conclude the bargain until he has made further manifestation of assent. b. Did the offer expire? i. Caldwell v. Cline—dispute as to whether the offer began to run from date sent or received. Offer becomes effective when offeree receives it and then time begins to run. ii. Trexton v. Froelich—phone negotiations to purchase with buyer leaving deal open at end of conversation. Tried to call back later and take same offer—question as to whether the offer was still open. Could still be open or could have indicated new offer. Offers remain open for a reasonable time. iii. As a general rule, the offeror controls the terms of the offer. They designate offeree, time of expiration, method of acceptance. If no expiration then expires after ‘reasonable’ time, if no mode of acceptance designated then offeree free to choose method. 1. Allied Steel v. Ford Motor Co.—contract to install machinery, amendment to indemnify (not signed) and accident happened. Allied claimed had not accepted because not signed. Court held that beginning performance was acceptance (unless certain way specified). c. Was the Offer Terminated or Revoked? i. R 2d §36— 1. an offeree’s power of acceptance can be terminated by: a. rejection or counter offer by the offeree (R 2d §39), b. lapse of time, or c. revocation by offeror (by reliable source or actions—Patterson v. Pattberg—bond payoff) d. death or incapacity of offeror or offeree. 2. in addition, an offeree’s power of acceptance is terminated by the non-occurrence of any condition of acceptance under the terms of the offer ii. Offers become irrevocable by: 1. agreement (R 2d §87(1)) 2. beginning performance in unilateral contracts (R 2d §45), 3. reasonable reliance on contracts (R 2d §87(2)). d. Did Offer create an Option? i. Nominal Consideration for Options is fine— 3 1. Thomason v. Bescher—if recitation of consideration for option is in writing then it creates option 2. Marsh v. Lott—writing acknowledged nominal consideration for option. ii. R 2d §87(1)—An offer is binding as an option contract if it a. is in writing and signed by offeror, recites a purported consideration for making of the offer, an proposes an exchange on fair terms within a reasonable time. iii. U.C.C. §2-205 (Firm Offers)—An offer by a merchant to buy or sell goods in a signed writing which gives assurance that it will be held open is not revocable for lack of consideration. Any assurance by offeree must be signed by offeror. iv. R 2d §87(2)—An offer which the offeror should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance of a substantial character on the part of the offeree before acceptance and which does induce such action or forbearance is binding as an option contract to the extent necessary to avoid injustice. 1. James Baird v. Gimbel Bros.—subcontractor underestimated cost, contractor used bid to get contract, sub notifies of mistake. Held no contract (notified before awarded contract) 2. Drennan v. Star Paving Co.—subcontractor makes bid and contractor uses it in master bid. Cannot revoke because accepted and used. Allowed reliance whereas Gimbel did not follow this logic. e. Was it for a bilateral or unilateral contract? i. R 2d §32—in case of doubt, an offer is interpreted as inviting the offeree to accept either by promising to perform or by rendering performance as the offeree chooses. ii. R 2d §62— 1. where an offer invites an offeree to choose between acceptance by promise or performance, the tender or beginning of performance is acceptance by performance. 2. such an acceptance operates as a promise to render complete performance. a. Brackenbury v. Hodgkin—mother asks daughter to come and take care of her, then she wants her out. Court holds that acceptance was when she moved away from her home to her mother’s home so performance on mother’s part is enforceable. Now daughter is on hook to finish or mother no longer obligated. iii. Bilateral—a promise in exchange for another promise (presumption for bilateral when it is not clear R 2d §32) 4 1. Davis v. Jacoby—request of couple to come from Canada to CA to care for husband and wife. Man died before they left Canada. Question as to whether unilateral (seeking performance of coming) or bilateral (seeking promise to come). Held that it was bilateral and enforceable after his death since they had promised. iv. Unilateral—a promise in exchange for performance 1. Traditional rule is that offeror can revoke until actual performance (Patterson v. Pattberg) 2. R 2d §45— a. when an offer invites an offeree to accept by rendering a performance and does not invite a promissory acceptance, an option contract is created when the offeree begins the invited performance or tenders the beginning of it. b. the offeror’s duty of performance under any option contract so created is conditional on the completion or tender of invited performance in accordance with terms of offer. 3. Cobaugh v. Klick Lewis, Inc.—unilateral contract—prize in exchange for performance of hole in one. 5 IV. Acceptance a. Was the offer accepted? i. Traditional Rules—Livingstone v. Evans—back and forth with last correspondence being offeror’s no less than $. Tried to accept but already sold—court held that original offer was still open and acceptance bound the offeror. 1. Mirror Image—if the acceptance is not exactly same as offer then it is a counter offer. 2. Last Clear Chance—the last person to submit something gets their terms to prevail. ii. Battle of Forms— 1. U.C.C. §2-207— a. A definite and seasonable expression of acceptance or a written confirmation which is sent within a reasonable time operates as an acceptance even though it states terms that are additional to or different from those offered or agreed upon, unless acceptance is expressly made conditional on assent to the additional or different terms. b. The additional terms are to be construed as proposals for addition to the contract. Between merchants such terms become part of the contract unless: i. The offer expressly limits acceptance to terms of the offer, ii. They materially alter it, or iii. Notification of objection to them has already been given or is given within a reasonable time after notice of them is received. c. Conduct by both parties which recognizes the existence of a contract is sufficient to establish a contract for sale although the writings of the parties do not otherwise establish a contract. In such cases, the terms of the particular contract consist of those terms on which the writings agree, together with any supplementary terms incorporated under any other provisions of this act. iii. If conflicting terms then: 1. Gap fillers—if contract does not specify terms then the terms are filled in with the provisions of the UCC. 2. Offeror’s terms prevail 3. Additional terms are incorporated into the contract (not when terms are conflicting) 6 iv. Idaho Power Co. v. Westinghouse Electric Corp.—Terms of sale for switch, dispute when it malfunctions. Court applies provisions of U.C.C. §2-207 and holds that no additional terms are implied. v. FLOW CHART FOR §2-207 Definite and Seasonable Acceptance? (§2-207(1)) If no then no contract If yes then is it a conditional assent? If no, is contract—if additional terms and merchants: (§2-207(2)) If yes, no contract Is there conduct that suggests contract? (§2-207(3)) If yes, terms are what writings agree on and gap fillers If no, then contract on offeror’s terms Arbitration clauses are typically material Additional terms cannot change terms already agreed upon If yes, on offeree’s terms unless: 1. offer limits terms of offer 2. materially alter 3. notification of objection vi. Method of Acceptance— 1. If not clearly stated, then any method that is equivalent to preferred method is fine. 2. Silence/Inaction— a. R 2d §69—where an offeree fails to reply to an offer, his silence and inaction operates as an acceptance in the following cases only: i. Where an offeree takes the benefit of offered services with reasonable opportunity to reject them and reason to know that compensation is expected (Implied contract) ii. Where the offeror has started or given offeree reason to understand that assent may be manifested by silence or inaction and offeree, by remaining silent or inactive, intends to accept offer. 7 b. ProCD, Inc. v. Zeidenberg—Database provider sells versions for consumers and for commercial at different prices. Consumers must agree to terms when use. Contract is binding even though can’t see terms at purchase. Ok to buy now, terms later. c. Hill v. Gateway 2000, Inc.—purchase of computer with terms in box (providing arbitration clause). Had opportunity to send back but didn’t so accepted terms. 3. Non conforming response a. U.C.C. §2-204—contract for sale of goods may be made in any manner sufficient to show agreement, including conduct by both parties which recognizes the existence of such a contract. vii. When did acceptance take place? 1. R 2d §63—Mailbox Rule—Unless the offer provides otherwise: a. An acceptance made in a manner and by a medium invited by offer is operative and completes the manifestation of mutual assent as soon as put out of offeree’s possession, without regard to whether it reaches the offeror; but b. An acceptance under an option contract is not operative until received by offeror. 2. Acceptance by Performance—Unilateral Contracts— a. R 2d §32—in case of doubt, an offer is interpreted as inviting the offeree to accept either by promising to perform or by rendering performance as the offeree chooses. b. R 2d §62— i. where an offer invites an offeree to choose between acceptance by promise or performance, the tender or beginning of performance is acceptance by performance. ii. such an acceptance operates as a promise to render complete performance. c. Brackenbury v. Hodgkin—mother asks daughter to come and take care of her, then she wants her out. Court holds that acceptance was when she moved away from her home to her mother’s home so performance on mother’s part is enforceable. Now daughter is on hook to finish or mother no longer obligated. 8 V. Consideration—R 2d §2—Promises—a promise is a manifestation of an intention to act or refrain from acting in a specified way, so made as to justify a promise in understanding that a commitment has been made. a. Bargain Theory— i. R 2d §71—Requirement/Types of Exchange 1. To constitute consideration, a performance or return promise must be bargained for. 2. A performance or return promise is bargained for if it is sought by the promisor in exchange for his promise and is given by the promisee in exchange for that promise. 3. The performance may consist of: a. An act other than a promise, or b. A forbearance, or c. The creation, modification, or destruction of a legal relation. 4. The performance or return promise may be given to the promisor or to some other person. It may be given by the promisee or by some other person. ii. Hamer v. Sidway—uncle promised $5K if nephew refrained from certain behavior. Nephew did, so the promise was enforceable— exchange was forbearance. b. Inducements— i. Earle and Simmons—court found that promise to pay if attend funeral (promise was sought after) and prize money for catching a fish (performance sought after) were both valid exchanges. ii. Whitten—promise not to call in exchange for gifts not valid because she wrote k and no evidence that he wanted her not to call (not sought after performance). iii. R 2d §81—Consideration as Inducement 1. The fact that what is bargained for does not itself induce the making of a promise does not prevent it from being consideration for the promise. 2. The fact that a promise does not itself induce performance or return promise does not prevent the performance or return promise from being consideration for the promise. c. Forbearance—there are two tests to determine if this is adequate consideration—Duncan requires both good faith and base for claim, R 2d §74 only requires one or the other. i. Duncan v. Black—promise not to sue—if a forbearance from exercising a legal right is to be enforceable then: the claim must have been made in good faith and not have been baseless. ii. R 2d §74—Settlement of Claims 1. Forbearance to assert the surrender of a claim or defense which proves to be invalid is not consideration unless— 1. The claim or defense is in fact doubtful because of uncertainty as to the facts or the law, or 9 2. the forbearing or surrendering party believes that the claim or defense may be fairly determined to be valid. iii. Pre-existing Duty—generally not consideration, even for 3rd parties. Exceptions: 1. new detriment 2. supervening problems that affect basic assumption of contract d. Was Consideration Adequate? i. Nominal (sham) consideration—courts will not enforce bargains that have sham consideration—must truly be a bargain. 1. Fischer v. Union Trust. Co—father tried to give daughter a deed and promise to pay mortgages (got $1 in return). Didn’t pay mortgages—won’t enforce because no consideration or sham consideration. 2. Schnell v. Nell—promise to pay $200 in installments in exchange for $0.01 is not consideration. ii. Not all unequal exchanges are considered to be nominal— 1. Batsakis v. Demotsis—promise to pay $2000 in exchange for about $25—borrower needed money to survive. Court does not inquire as to terms or uneven bargaining power and upholds bargain. 2. Embola v. Tuppela—promise to pay $10,000 in exchange for $50 to recover mine in Alaska (long shot). Promise was enforceable because he needed money and other party took the gamble. iii. Consideration based on past benefit— 1. R 2d §86—Promises for Benefits Received a. A promise made in recognition of a benefit previously received by the promisor from the promisee is binding to the extent necessary to prevent injustice. b. A promise is not binding under section 1 i. if the promise conferred the benefit as a gift or for other reasons the promisor has not been unjustly enriched, or ii. to the extend that its value is disproportionate to the benefit. 2. Mills v. Wyman—promise to pay for sick son’s care after he has died. Court holds not enforceable promise for past benefit received. 3. Webb v. McGowin—promise to pay for saving him from being hit by log—had begun payments, terminated on death of promisor—court held that estate had to pay—perhaps because of preexisting payments 10 4. Harrington v. Taylor—promise to pay after being saved from ax blow to head—started payments then stopped—no obligation to continue payment 5. Factors to Consider for Past Benefit— a. Aspect of promise (timing, formality) b. Nature of past benefit (gift v. obligation) c. Conduct of promisor/promisee e. Was promise illusory? i. Examples— 1. Davis v. General Foods—could or not decide to use recipe—too indefinite 2. Nat. Nal. Service Stations v. Wolf—if buy gas then get discount—illusory because had choice not to buy any gas. However discount was applied to every small transaction when he did buy gas. 3. Obering v. Swain-Roach Lumber—if lumber company bought land and removed timber then family would buy from them. After purchase at auction, family refuses to purchase. Binding at moment company purchased because no repudiation before condition was met and binding on both parties. ii. Ways to avoid problem of Illusory Promises 1. Define commitment very broadly—finding commitments in slight limits of discretion 2. Finding that alternative promises can be consideration if each one could be consideration. a. R 2d §77—a promise or apparent promise is not consideration if by its terms the promisor or purported promisee reserves a choice of alternative performances unless: each of the alternative performances would have been consideration if it alone had been bargained for. b. Paul v. Rosen—promise to sell liquor store if can secure lease—alternative promises are 1. buy inventory or 2. not get lease—second option is not consideration so whole deal fails. 3. Finding implied duties that serve as commitments— a. Wood v. Lucy, Lady-Duff Gordon—agreed to let Wood endorse all fashion choices. LDG argues Wood’s promise is illusory—implied obligations makes contract binding. b. Omni Group v. Seattle First-National Bank— promise to sell property for $, sale conditioned on satisfactory reports. Promise to obtain reports is implied duty of good faith so contract is valid. 11 c. Feld v. Henry S. Levy and Sons—promise to sell all breadcrumbs made. Court held duty to provide even if stop production until contract cancelled. d. U.C.C. §2-306—Output requirements and Exclusive Dealing— i. a term which measures the quantity by the output of the seller or the requirement of the buyer means such actual output or requirements as may occur in good faith.... ii. a lawful agreement by either the seller or buyer for exclusive dealing in kind of goods concerned imposes an obligation by seller to supply goods and to buyer to promote their sale. f. Is it an adjustment to a preexisting contract? i. Traditional rule required consideration for adjustments: 1. Levine v. Blumenthal—no change to the lease terms (reduce price) because no consideration for second bargain. 2. U.C.C. §2-209 a. An agreement modifying a contract within this article needs no consideration to be binding (overrules Levine) b. A signed agreement which excludes modification or recission except by signed writing cannot be otherwise modified or rescinded, but with merchants can be done with form of one signed by other c. Statute of frauds provision— 3. R 2d §89—A promise modifying a duty under a contract not fully performed on either side is binding: a. if a modification is fair and equitable in view of the circumstances not anticipated by the parties when the contract was made, or b. to the extent provided by statute c. to the extent that justice requires enforcement in view of material change of position in reliance on that contract. 12 VI. Implied Contracts/Estoppel a. Implied in fact—where a party takes a benefit whether silently or passively with knowledge that the provider expects compensation. Provider must have reasonable expectation of payment. Can recover the reasonable value of the services under these contracts. i. Martin v. Little, Brown & Co.—man reports plagiarism of a book to publishing company. Publisher sends $200 honorarium, guy wants 1/3 of copyright infringement award. Claimed implied in fact contract—no reasonable expectation of compensation. ii. Collins v. Lewis—dispute over the boarding of cows. Notified owner that they would be billed for upkeep/boarding of cows. Implied in fact contract because of action of parties. iii. Seaview Ass’n of Fire Island, NY v. Williams—dispute over payment of homeowners dues—court held implied k because owners had constructive knowledge of association’s activities. (could also be implied in law) b. Is Estoppel Appropriate? i. Promissory Estoppel—party is estopped because other party relied on their promise 1. Kirksey v. Kirksey—Woman was induced to move by brother-in-law’s promise of a place to stay. Court held that no enforceable promise to provide place to stay because gratuitous promise—one member of court thought moving was consideration enough to bind. 2. Prescott v. Jones—dispute over whether letter was promise to renew insurance policy on building—court said no consideration and no reliance on promissory estoppel. ii. Estoppel as applied in Contract Law— 1. R 2d §90—promise reasonably inducing action or forbearance a. a promise which a promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance on the part of the promisee or a third person and which does induce such action or forbearance is binding if injustice can be avoided only by enforcement of the promise. The remedy granted for breach may be limited as justice requires. b. a charitable subscription or marriage settlement is binding under subsection (1) without proof that the promise induced action or forbearance. 2. Ricketts v. Scothern—reliance on note to stop work—no consideration but reliance--court uses estoppel to enforce the obligation. 3. Allegheny College v. National Chautauqua County Bank—promise to give for scholarship, paid some—court 13 held was implied contract with consideration (named fund)—no use of estoppel because no reliance. 4. East Providence Credit Union v. Geremia—insurance lapse—bank held to have promised to maintain—no estoppel but implied contract (bargain with consideration). 5. Hoffman v. Red Owl—application of promissory estoppel to case where man thought he was getting a store. Case criticized because not clear that Hoffman relied on any promise to his detriment. 6. Goodman v. Dicker—told had franchise for Emerson radios—no franchise granted—applied promissory estoppel—this may be closer to fraud/misrepresentation. 7. Forrer v. Sears, Roebuck & Co.—man induced to return to work at Sears after retirement, reliance on promise for lifetime employment—court held no extra consideration for lifetime employment so no enforcement—going back to consideration theory? 8. Hunter v. Hayes—promise for job as flagger, quit job as telephone operator. Never gave her the job so relied on promissory estoppel to get recovery. 9. Stearns v. Emery Waterhouse Co.—induced to work for EW by promise of 5 year contract. Not in writing so had to rely on promissory estoppel (would have violated statute of frauds). Contract was enforceable. 10. R 2d §139— a. A promise which the promisor should reasonably expect to induce action or forbearance on part of the promisee and which does NOT induce the action or forbearance is enforceable not withstanding the statute of frauds if injustice can be avoided only by enforcement of the promise. Remedy can be limited as justice requires. 11. NC only allows defensive estoppel c. Implied in law/Quasi contract—where a party confers a benefit on another party and the other party would be unjustly enriched if it were not required to return (or compensate for) the benefit. i. Volunteers cannot recover under this type of contract. ii. Can recover amount of benefit conferred on other party (restitution) under these contracts. iii. Remedy for invalid contracts 14 VII. Contract Validity a. Are the parties competent? i. contracts by minors and mentally ill are voidable by person lacking competency. Exceptions are for minors contracting for necessaries (food, shelter) and certain other contracts (insurance, banking, student loans). Promises can be ratified, reaffirmed when minor reaches majority. 1. R 2d §14—Infancy— 2. R 2d §15—Mental Illness or Defect— b. Was there fraud or misrepresentation? i. R 2d(TORTS) §525—one who fraudulently makes a misrepresentation of fact, opinion, or intention of law for the purpose of inducing another to act or refrain from action in reliance upon it, is subject to liability to the other in deceit for pecuniary loss caused to him by his justifiable reliance. ii. R 2d §164—if a party’s manifestation of assent is induced by either fraudulent or a material misrepresentation by the other party upon which the recipient is justified in relying, the contract is voidable by the recipient. 1. Types of fraud/misrepresentation: a. Innocent b. Negligent c. Fraudulent iii. Constructive Fraud—arises most often in confidential relationships or mutual mistake cases 1. Jackson v. Seymour—sister wants recission of deed because land wasn’t what was represented to her. Cannot prove actual fraud but got judgment in favor on constructive fraud. iv. Warranty 1. Tribe v. Peterson—man claimed horse was sold with ‘no buck’ guarantee, or misrepresentation because horse threw him. Court held no such warranty and no misrepresentation. 2. Hinson v. Jefferson—land sold restricted to residential but septic field prevented building. Held could rescind based upon mutual mistake of fact or implied warranty. v. Concealment 1. R 2d §160—action intended or known to be likely to prevent another from learning a fact is equivalent to an assertion that the fact does not exist. vi. Disclosure 1. R 2d §161—A person’s non-disclosure of a fact known to him is equivalent to an assertion that the fact does not exist in the following cases only: 15 a. disclosure prevents a prior disclosure from being a misrepresentation b. disclosure would correct a mistake as to basic assumption on which deal is based, or would be given in good faith c. disclosure would correct mistake as to contents of deal in writing d. other party is entitled to disclosure because of relationship 2. Courts are likely to require disclosure if: a. information is latent as opposed to patent b. information is necessary to update or correct previously disclosed info c. parties are in a fiduciary or confidential relationship d. information is illegally or tortiously acquired e. the uninformed party is the buyer or lessee f. uninformed party is sympathetic g. informed party engages in bad behavior. 3. Kleinberg v. Ratett—k to buy land free of encumbrances— had stream running through it. Could be non-disclosure (sellers knew) but held no recovery under caveat emptor c. Was there a mistake by one or both of the parties? i. Unilateral Mistake—R 2d §153—where a mistake of one party at time of contract was made as to a basic assumption on which he made the contract has a material effect on the agreed exchange of performances, that is adverse to him, the contract is voidable by him if he does not bear the risk of mistake under §154. 1. the effect of the mistake is such that the enforcement of the contract is unconscionable 2. the other party has reason to know of the mistake or his fault caused the mistake. ii. Bilateral Mistake—R 2d §152—where a mistake of both parties at the time the contract was made as to the basic assumptions on which the contract was made has a material effect on the agreed exchange of performances, the contract is voidable by the adversely affected party, unless they bear the risk of mistake under §154. 1. R 2d §154—a party bears the risk of mistake when— a. the risk is allocated by agreement of the parties b. he is aware at the time the contract was made that he has limited knowledge with respect to the facts to which the mistake relates but treats limited knowledge as sufficient. c. the risk is allocated to him by the court on the ground that it is reasonable under the circumstances to do so. 16 2. Sherwood v. Walker—dispute about cow’s ability to bear a calf. Price agreed to was for barren cow—fertile much more. Held that there was a mutual mistake of fact. 3. Beachcomber Coins v. Boskett—rare dime discovered to be counterfeit. Purchaser can get money back because mutual mistake of fact. 4. Smith v. Zimbalist—prominent violinist thought fake violins were real and paid a lot of $ for them. Held as express warranty since they were described as authentic on bill of sale. Entitled to $ back. d. Was the contract unconscionable? Where there both procedural (surprise) and substantive unfairness (unequal bargaining power) issues? i. U.C.C. §2-302—if the court, as a matter of law, finds the contract or any clause of the contract to have been unconscionable at the time made, the court may refuse to enforce the contract or it may enforce the remainder of the contract without the unconscionable clause, or it may so limit the application of any unconscionable clause to avoid any unconscionable result. 1. Williams v. Walker-Thomas Furniture—Woman buys stuff on bad credit arrangement—court found to be unconscionable 2. Gianni Sport Ltd. v. Gartos—had term in contract that said could cancel at any point before shipping—court found to be unconscionable—could also be illusory 3. Waters v. Min—woman induced to sign away annuity policy—found to be unconscionable ii. R 2d §205—every contract imposes on each party a duty of good faith and fair dealing in its performance and enforcement. 17 VIII. Interpretation of the Contract Four Corners Four Corners (Plain Meaning) Contextual To determine if ambiguous Text (document) Text (words) To determine the meaning Context and extrinsic evidence Context and extrinsic evidence Context and extrinsic evidence Dealing/performance/trade Context and extrinsic evidence U.C.C. §2-202 n/a a. Two approaches: i. Four Corners Rule—uses text of contract to see if ambiguous and if so turn to extrinsic evidence for clarification. 1. Bethlehem Steel v. Turner Construction—dispute over price for steel. Court used four corners approach to hold that language of contract permitted price increase by subcontractor at will. 2. Federal Dep. Ins. V. W.R. Grace—use of four corners cuts down on litigation. Disagreement over terms does not mean ambiguity. ii. Contextualism—look at both text and extrinsic evidence to determine if ambiguous, use extrinsic evidence to clarify. 1. Robert Industries v. Spence—advocating contextualism 2. Pacific Gas v. G.W. Thomas Drayage—disagreement over who indemnity clause covers—appellate court used contextualist approach—“if the court decides, after considering extrinsic evidence, that the language of a contract, in light of all of the circumstances, is fairly susceptible to either one of two interpretations contended for, extrinsic evidence relevant to prove either of such meanings is admissible” 3. Spaulding v. Morse—looked at reasons for support of son to determine whether or not contract was enforceable. 4. R 2d §212—a question of interpretation of an integrated agreement is to be determined by the trier of fact if it depends on the credibility of extrinsic evidence or a choice among reasonable inferences. Otherwise it is a question of law. 5. U.C.C. §2-202—terms of contract may be explained...by course of dealings or usage of trade or course of performance. b. Parol Evidence Rule—a writing intended as a final agreement should be protected from efforts to prove inconsistent terms, and in some cases, supplemental terms as well. 18 2. 3. 4. 5. a. An integrated agreement discharges inconsistent terms, and if it is a completely integrated agreement, it discharges supplemental terms as well. b. Questions: i. Is the prior agreement a separate deal, one based on separate consideration? R2d § 216(2)(a) ii. If not, is there an integrated agreement? R2d § 209 1. A writing or writings constituting a final expression of one or more terms of an agreement. R2d § 209 2. If writing reasonably appears to be complete, it is presumably an integration. 3. Prior agreements or negotiations are admissible to establish whether an agreement is integrated or partial R 2d §214(a) iii. Is the integration partial or complete? 1. If partial, it discharges inconsistent prior agreements R2d § 213(1) 2. If complete it discharges inconsistent prior agreements as well as all prior agreements within its scope. R2d § 213(2) 3. Prior agreements or negotiations are admissible to establish whether the integration is complete or partial. R2d § 214(b) 4. Merger clause (“this agreement includes all terms…) is strong evidence of complete integration, perhaps conclusive under 4 corners rule. c. Is prior agreement one that might naturally be omitted form an otherwise complete integration? i. If so, the agreement is not discharged unless the agreement expressly forecloses this (through a merge clause, for example). R2d § 216(2)(b) d. Even if these are proven, then it becomes a question of fact for the jury. Mitchill v. Lath—Dispute over removal of ice house on property—court found that contract was complete and thought that removal of ice house would have been something that would have been in writing so seller did not have to remove. Hatley v. Stafford—lease of land for growing wheat, had buyout option. Court holds that oral evidence was relevant because no specific time for buyout in contract, so oral was relevant. Court looks to circumstance to determine if this was something that should have been in contract-held that it was not. Hayden v. Hoadley—an oral term in direct conflict with written contract will not be admitted. Interpretative Canons— a. Always construed against drafter b. Lists are always exclusive or exhaustive c. Specific terms trump general ones 19 b. Does it involve a Standardized Form?—there is a duty to read these contracts (contracts of adhesion) but there are a number of exceptions to that rule: 1. contract/term not legible or comprehensible 2. contract/term not sufficiently brought to attention of offeree 3. drafter of contract/term misrepresents the content of the contract/term ii. Agriculture Insurance Co. v. Constantine—garage ticket is held not to be a contract. Actually a bailment for hire. iii. Sharon v. City of Newton—signed release form for sport but was injured. Court held that this was sufficient notice to bind them to the agreement (had time to look, etc.) iv. Mundy v. Lumberman’s Mut. Cas. Co.—change in insurance policy terms that limited liability. Term in large print and held to be sufficient notice. v. Weisz v. Parke-Bernet Gallaries—dispute over terms of sale at gallery auction—held that disclaimer about authenticity was sufficient. vi. Henningsen v. Bloomfield Motors—defect in car caused wreck, dispute over terms of limited warranty—held that small type, info buried on back of form was inadequate notice. c. Is there an express or implied warranty? i. U.C.C. §2-313—express warranties 1. Express warranties by the seller are created as follows: a. any affirmation of fact or promise made by seller to buyer that relates to goods and becomes part of basis for bargain creates express warranty. b. any description of goods that made part of basis for bargain creates express warranty that goods will conform to description ii. U.C.C. §2-314—implied warranties—unless otherwise excluded or modified, there is an implied warranty that goods are not defective 1. U.C.C. §2-316—to change or modify that implied warranty, language must be conspicuous and in writing 20 IX. Impossibility and Impracticability a. Is the contract impossible to perform? i. Traditional—if the performance depends on existence of something that no longer exists, then not required to perform. 1. Taylor v. Caldwell—contract to use concert hall that burned to ground before first concert—court held excused from performance because of impossibility. 2. Tompkins v. Dudley—school house burned down after projected finish date but before finished—court held not impracticable or impossible—just have to rebuild at their cost ii. R 2d §262—Death or Incapacity of Person Necessary for Performance. iii. R 2d §263—Destruction, Deterioration, or Failure to Come into Existence of thing Necessary for performance iv. R 2d §264—Prevention by government regulation or order 1. Louisville and Nashville RR v. Crowe—passes were invalid because of government regulation—were entitled to value of land given minus the value of used pass 2. Isle of Mull—no responsibility to charterers when boat was requisitioned by army b. Is the contract impracticable to perform? i. R 2d §261—Impracticability—Where, after a contract is made, a party’s performance is made impracticable without his fault by the occurrence of an event the non-occurrence of which was a basic assumption on which the contract was made, his duty to render that performance is discharged, unless the language or the circumstance indicates the contrary. ii. Impracticability—where impractical, performance is discharged if: 1. occurrence of an event the non-occurrence of which was a basic assumption, unless 2. circumstances indicate the contrary 3. parties allocate risk of impracticability to party asserting it, or 4. nature of contract allocates risk to that party 5. the party is in a better position to avoid losses (insurance) 6. the fact that a supervening event was not foreseeable may be relevant iii. Kel Kim v. Central Markets—lease required insurance, insurance market gone bad. Court held that they could have avoided risk by getting insurance so no excuse from performance. c. Commercial Impracticability i. American Trading Prod. v. Shell Int’l Marine—carry oil from TX to Bombay. Suez canal closed so had to go way around. Tried to 21 recover additional cost under either impossibility or impracticability—court said no, another route known and held that extra cost not unreasonable. ii. U.C.C. §2-615—Impracticability—Comment 4—increased cost alone, even market collapse, may not excuse performance iii. Maple Farms v. City School District—example of comment 4— price increase not enough to discharge. iv. Mishara Construction v. Transit Mixed Concrete—strike at jobsite, concrete company claimed couldn’t deliver concrete— sometimes this works—jury question. b. Doctrine of Frustration of Purpose i. Krell v. Henry—rented room to see coronation, king got sick so no need. The underlying purpose was gone but room could still be rented. Not responsible for rest of $. ii. R 2d §265—where, after a k is made, a party’s principal purpose is substantially frustrated without his fault by the occurrence of an event the non-occurrence of which was a basic assumption on which the contract was made, his remaining duties to render performance are discharged, unless the language or the circumstances indicate to the contrary. iii. Key questions: 1. is the primary purpose frustrated? 2. is there some reason that the asserting party should bear the risk 22 X. Breach a. Damages—R 2d §344—three types of damages i. Measured by loss/gain of the non-breaching party 1. Acme Mills v. Johnson—the damage was calculated at the time of the breach, not at time of contract. ii. Expectation—two measures 1. expected profits/gains + reliance costs a. Rockingham Co. v. Luten Bridge Co.—bridge company wanted damages for full price but could only recover expenditures + loss profits. Duty to mitigate introduced. b. Louise Caroline Nursing Home v. Dix Const.— construction company breached but cost to finish was less than contract price, so no damage. 2. R 2d §347—(used in Hawkins v. McGee) injured party has right to damages based upon his expectation interest as measured by: a. Loss in value to him of the other party’s performance caused by failure, deficiency, plus b. Any other loss, including incidental or consequential (not reliance), less c. Any cost/loss that has been avoided by not having to perform iii. Reliance—reimbursement for loss caused by reliance on the contract; cost to get plaintiff back to position if contract had never happened 1. Sullivan v. O’Connor—court awarded only reliance, not expectation iv. Restitution—restore any benefit that one conferred onto breaching party; value of benefit 1. Party can go off the contract to recover in restitution b. Limitation on Damages i. Mitigation—introduced in Luten Bridge 1. overhead expenses do not mitigate a. Leingang v. City of Mandan Weed Board— overhead costs related to the specific should not be deducted from the award, but general costs can. 2. if no substitute then market value is measure of damage 3. Loss volume seller theory—a second/additional transaction does not mitigate damages for the breach if the transaction could have taken place absent the breach. However, the second transaction does mitigate if it is made possible by the breach. 23 a. Kearsarge Computer v. Acme Staple Co.—new contract after breach. If could have done both then no mitigation 4. Must use reasonable effort to find comparable or substantially similar job a. Parker v. 20th Century Fox—dispute over whether 2nd movie deal offer was similar enough to mitigate b. R 2d §350—“loss avoided without undue risk, burden or humiliation”—if find another job, even if inferior, then mitigation. ii. Consequential Damages/Foreseeability 1. R 2d §351— a. Damages are not recoverable for loss that party in breach did not have reason to foresee as a probable result of the breach when the contract was made b. Loss may be foreseeable as a probable result of a breach because it follows from the breach i. In the ordinary course of events ii. As a result of special circumstances beyond the ordinary course of events, that the party in breach had reason to know c. A court may limit damages for foreseeable loss by excluding recovery for loss of profits, by allowing recovery only for loss incurred by reliance if justice requires to avoid disproportionate compensation. 2. Hadley v. Baxendale—no way to know that the delay in crankshaft would shut down the mill. 3. Lamkins v. International Harvester Co.—tractor without lights, tried to sue for lost crop—is this foreseeable? iii. Uncertainty of profits 1. R 2d §352—damages are not recoverable for loss beyond the amount that the evidence permits to be established with reasonable certainty a. Freund v. Washington Square Press—breach to publish book, could not establish profits, no damages. b. Fera v. Village Plaza—breach on commercial lease—no guarantee of profits, no damages c. Chicago Coliseum Club v. Dempsey—no establishment of profits so can’t get damages on it 2. R 2d §349—as an alternative to damages measured in §347, plaintiff has right to damages based on reliance interest, including expenditures made in preparation of performance or in performance, less any loss defendant can prove with reasonable certainty that plaintiff would have incurred if contract had been performed 24 a. Anglia Television v. Reed—no show for play—was entitled to preparation expenditures b. Security Stove v. American Ry.—breach to deliver stove, recover preparation damages but not profits (not certain of amount) c. Liquidated Damages—cannot provide for this in a contract as a penalty for a breach. i. R 2d §356—damages for breach by either party may be liquidated in the agreement but only at amount that is reasonable in light of anticipated or actual loss caused by breach and the difficulties of proving loss. A term fixing unreasonably large liquidated damages is unenforceable on grounds of public policy as a penalty. d. Restitution—unjust enrichment/quantum meruit i. Off contract when contract is void or unenforceable 1. R 2d §370—a party is entitled to restitution under the rules stated here only to the extent that he has conferred a benefit on the other party by way of performance or reliance. 2. Boone v. Coe—k not enforceable b/c of statute of frauds (over one year performance to TX), but part performance so restitution a. R 2d §375—not barred from restitution because k unenforceable under statute of frauds. 3. Kearns v. Andree and Farash v. Sykes—k not enforceable so only restitution interest is available ii. Off contract when contract is enforceable 1. R 2d §371—if a sum of money is awarded to protect a party’s restitution interest, it may be as justice requires be measured by either: a. Reasonable value to other party of what was received in terms of cost to obtain from person in claimant’s position b. Extent to which the other party’s property has been increased in value or other interests advanced 2. U.S. v. Algernon Blair—chose to get restitution because would have lost money on either expectation or reliance since were in losing contract. iii. Measure of damages for total breach of contract 1. R 2d §373—Party is entitled to restitution for any benefit that he has conferred on the other party by way of part performance or reliance. The injured party has no right to restitution if they have performed all of their duties under the contract and all that remains of other party’s performance is payment of a certain sum of money. 2. Oliver v. Campbell—couldn’t recover in restitution because performance was completed—was limited to balance unpaid on contract. 25 iv. Part performance 1. R 2d §374—if a party refuses to perform on the ground that his remaining duties of performance have been discharged by the other party’s breach, the party in breach is entitled to restitution for any benefit conferred in excess of the loss he has caused by own breach. 2. Britton v. Turner—k for flat fee for year’s work. Can recover for value of 9 months of service less damages to non-breaching party. e. Specific Performance/injunctive relief— i. R 2d §359—specific performance or an injunction will not be ordered if damages would be adequate to protect the expectation interest of the injured party. ii. R 2d §360—in determining whether the remedy in damages would be adequate, the following circumstances are significant: 1. the difficulty of proving damages with reasonable certainty 2. the difficulty of procuring suitable substitute performance by means of money awarded as damages, and 3. the likelihood that award of damages could not be collected iii. Limitations—even if damages are not adequate, specific performance or injunction is not granted if: 1. disproportionate burden on defendant 2. significant/ongoing court supervision is required iv. courts rarely force parties to affirmatively perform—but will issue negative injunctions (covenants not to compete) but even those are narrow. 26