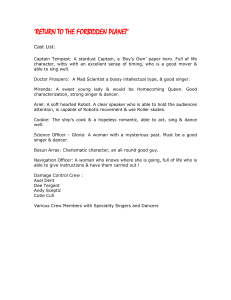

The Unthinkable & Unlivable Singer

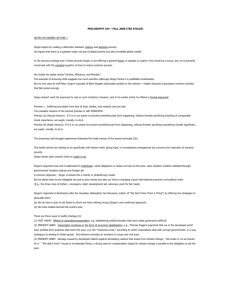

advertisement