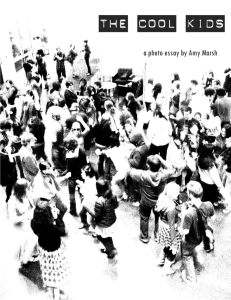

The New Gnostics: The Semiotics of the Hipster

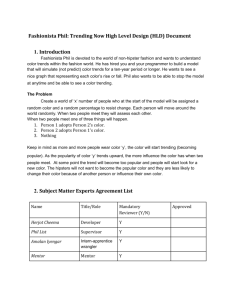

advertisement