FORUM

When “Real” Seems Mediated: Inverse Presence

Abstract

As our lives become increasingly dominated by mediated

experiences, presence scholars have noted that an increasing number of these mediated experiences evoke (tele)presence, perceptions that ignore or misconstrue the role

of the medium in the experience. In this paper we explore

an interesting countertrend that seems to be occurring as

well. In a variety of contexts, people are experiencing not

an illusion that a mediated experience is in fact nonmediated, but the illusion that a nonmediated “real” experience

is mediated. Drawing on news reports and an online survey, we identify 3 categories of this “illusion of mediation”:

positive (when people perceive natural beauty as mediated), negative (when people perceive a disaster, crime, or

other tragedy such as the events of September 11, 2001, as

mediated), and unusual (when close connections between

people’s “real life” activities and mediated experiences lead

them to confuse the former with the latter). We label this

phenomenon inverse presence and consider its place and

value in a comprehensive theory of presence, its possible

antecedents and consequences, and what it suggests about

the nature of our lives in the 21st century.

“We kept waiting for Arnold [Schwarzenegger] to

march out of the ruins and watch the end credits roll.”

Anonymous journalist at the World Trade Center in

New York City, September 11, 2001. (Author, personal

communication, September 11, 2001)

ble. I think, ‘Oh, my God, am I really here?’ It’s a great

sensation. It’s like a movie.”

Florida’s First Lady Columba Bush, on her experience

in the mansion. (Barrs & Cabrera, 2002)

“And it’s true we are immune, when fact is fiction

and TV reality. . .”

Lyrics from “Sunday Bloody Sunday,” by the rock band

U2. (1982, track 1).

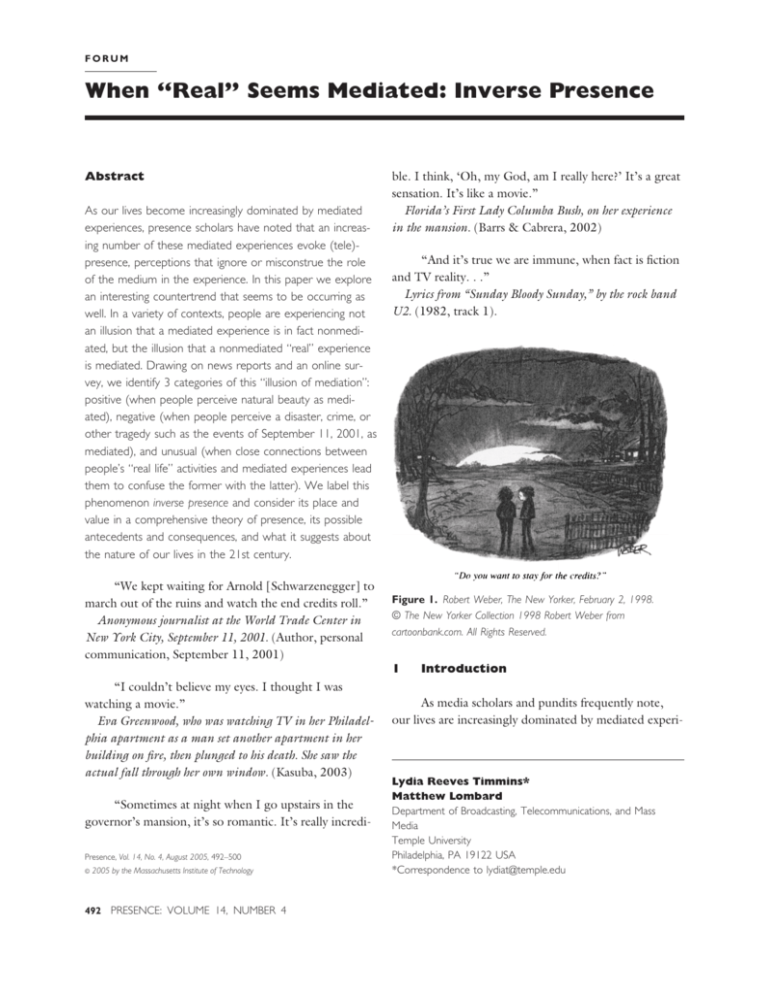

Figure 1. Robert Weber, The New Yorker, February 2, 1998.

© The New Yorker Collection 1998 Robert Weber from

cartoonbank.com. All Rights Reserved.

1

“I couldn’t believe my eyes. I thought I was

watching a movie.”

Eva Greenwood, who was watching TV in her Philadelphia apartment as a man set another apartment in her

building on fire, then plunged to his death. She saw the

actual fall through her own window. (Kasuba, 2003)

“Sometimes at night when I go upstairs in the

governor’s mansion, it’s so romantic. It’s really incrediPresence, Vol. 14, No. 4, August 2005, 492–500

©

2005 by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

492 PRESENCE: VOLUME 14, NUMBER 4

Introduction

As media scholars and pundits frequently note,

our lives are increasingly dominated by mediated experi-

Lydia Reeves Timmins*

Matthew Lombard

Department of Broadcasting, Telecommunications, and Mass

Media

Temple University

Philadelphia, PA 19122 USA

*Correspondence to lydiat@temple.edu

Timmins and Lombard 493

ences—traditional media including the telephone, radio,

television, film, newspapers, and magazines have been

joined by e-mail, instant messaging, chat rooms, cell

phones, video games, HDTV, the Web, simulator

amusement rides, and, soon, virtual reality. As presence

scholars have noted, an increasing number of these mediated experiences evoke (tele)presence, perceptions

that ignore or misconstrue the role of the medium in

the experience, perceptions that constitute an “illusion

of nonmediation” (Lombard & Ditton, 1997).

But as the quotations above suggest, an interesting

countertrend seems to be occurring as well. In a variety

of contexts, people are experiencing not an illusion that

a mediated experience is in fact nonmediated, but the

illusion that a nonmediated, “real” experience is mediated. In this paper we discuss this phenomenon, which

we label inverse presence, and consider its place and value

in a comprehensive theory of presence, its possible antecedents and consequences, and what it suggests about

the nature of our lives in the 21st century.

2

Why Study Inverse Presence?

Presence theory and research have evolved from

simple unidimensional definitions to sophisticated multidimensional ones, and from an intense focus on defining the core concept of presence to understanding its

relationship to other important and related concepts

and phenomena (e.g., immersion, involvement, flow,

empathy, and consciousness; Lombard & Bracken,

2003). A better understanding of these concepts and

phenomena helps us refine our theories regarding presence itself, and inverse presence represents another of

these key phenomena.

As communication and computer technologies advance we will continue to have not only more frequent

mediated experiences but more frequent presence experiences. There’s no reason the increasingly common

confusion regarding what is “virtual” (i.e., mediated by

technology) and “real” (i.e., nonmediated) should operate in only one direction. Confusions in which nonmediated experiences are mistaken for mediated ones

are increasingly likely and so also merit scholarly attention.

One of the key reasons presence is the subject of

study concerns its potential to affect the emotions,

judgment, learning, task performance, and so forth, of

those who experience it. Ironically, another potential

effect of having frequent presence experiences may be a

susceptibility to experience additional confusions regarding what is “real” and not, including inverse

presence. The possibility that presence makes inverse

presence more likely certainly merits study, and has

important implications (discussed below) for the role

of technology in our lives.

3

Explicating Inverse Presence

Chaffee (1991) notes that a good way to define

and understand a concept is to identify examples of the

phenomenon the concept is thought to represent.

Having informally gathered examples from media

reports and personal experiences, in which comments

such as “It felt like a movie” were common, we adopted

a more comprehensive approach by conducting several

searches using Google News (http://news.google.

com/). Over a period of one year we used the search

terms “like a movie,” “like a picture,” and “like a television” to identify media reports that might describe situations in which people had experienced the inverse of

(tele)presence. We also conducted a survey on the

World Wide Web, asking respondents if they ever had

an experience during which they felt they were part of a

mediated environment.1

We examined 376 results from seven searches conducted between February 2003 and January 2004, and

divided them into categories. We first excluded stories

1

The specific question wording was, “Have you ever felt like you

were living inside or actually experiencing a movie or TV show (or

another medium such as a video game) instead of the real world? If so,

please describe your experience (including when it happened, how it

felt, etc.) in the space below.” An invitation to complete the survey

along with the URL was distributed to a convenience sample via university listservs; 37 relevant responses were obtained. The goal was not

to assess the prevalence of inverse-presence experiences but to identify

examples of the phenomenon.

494 PRESENCE: VOLUME 14, NUMBER 4

that bore no relation to presence or inverse presence,

including those that mentioned film preferences (e.g.,

“I like a movie that features action” as part of a film review), contained references to specific technology (e.g.,

“like a movie camera” to describe a consumer electronics product), and compared one medium to another

(e.g., identifying satellite radio as being “like a movie

without pictures”). Another group of stories featured

the use of media experiences only as a reference point or

shorthand way to communicate information (e.g., a

Chicago reporter’s reference to the Blackhawks sports

team’s season as being “like a movie that was intended

to be a drama but turns out to be so bad it’s funny”

(Want a good. . ., 2003).

The remaining 97 stories in the search results fell into

three categories of reports of people perceiving nonmediated experiences as mediated ones:

1. Positive—stories in which people experience natural beauty and perceive it as a picture, nature documentary, or other mediated experience (14%;

n ⫽ 14).

2. Negative—stories in which people are involved in

a disaster, crime, or other tragedy and experience

it as if it were mediated; many examples featured

quotes from victims saying their experience

seemed “like a movie” (48%; n ⫽ 46).

3. Unusual—stories in which close connections between people’s “real life” activities and mediated

experiences lead them to confuse the two. Examples include actors or people in situations that are

fantastic (38%; n ⫽ 37).

In the following we discuss and provide examples of

some of the stories (and survey responses) in each of

these inverse-presence categories.

In Category 1, the person experiencing inverse presence experiences nonmediated beauty in nature as if it

were mediated. A merchant marine says, “The Middle

East is like a picture in National Geographic come to

life” (Midland man travels. . ., 2003). A columnist describes a ride on a train through Ohio’s Cuyahoga Valley, relating how “a landscape of mythical perfection

unreels like a movie before my hungry eyes” (Bloom,

2003). A respondent to the Web survey describes his

experience while hiking: “The view from [the] mountaintop is like something you’d only see in a movie. . .

picture-perfect.” While in some cases the comparison

may simply be a convenient way to communicate a familiar experience to a listener or reader, in many stories

the nature of the experience is unambiguous. In Steiner

(2004), a hunter describes the first day of deer season as

she begins to walk the trails in search of a buck:

The trail angled up to a high country lake that reflected the rocky peak above, a picture perfect postcard. The trail continued climbing, and at one point

I could look down into the blue-green pool I had

passed. Other mountains now framed the scene, another picture postcard. I got to the top of the mountain and turned to look at what was on the other side,

more snow-capped mountains and wildflower-studded

meadows, more picture postcards. I had seen such

scenes on TV and in the movies, and in paintings and

photographs. Was it real this time or just another imitation? (pp. 45– 47)

In this and other cases the people having the real,

nonmediated experience define and describe it as a mediated experience. One reason this happens may be because the intensity and perfection of the natural beauty

make it seem like it must have been created rather than

naturally occurring. Most of us have seen paintings,

photos, or videos that feature perfect clouds in a brilliant blue sky. But when with our own eyes we see the

sky above us looking the same way, we associate it with,

and at some level experience it as, a mediated experience.

In the second category of inverse-presence examples,

tragic reality is experienced as a mediated, artificial experience, usually a movie. A witness to a tour bus crash

that injured 50 people says, “It looked like a movie set”

(Packer, 2003). The mother of a San Bernardino, California, man shot and killed by police says, “It’s not real.

It’s like something that happened in a movie and not to

me” (Schexnayder, 2003). A witness to a police shooting in Yonkers, New York, says, “It was like a video

game. He falls down and says ‘I’m shot, I’m shot’”

(David, 2003). A respondent to the Web survey recalls

the experience of being diagnosed with a bipolar disor-

Timmins and Lombard 495

der: “I felt like it wasn’t really happening. I felt like I

was on a talk show or in an E! True Hollywood story.”

In many cases when a community suffers a trauma,

such as a fire or explosion, eyewitnesses tell reporters

that the experience was like watching a movie. In Philadelphia in January 2003 (Kasuba, 2003), a man set fire

to his girlfriend’s apartment and then climbed from balcony to balcony in the high-rise building, setting other

fires until he fell to his death. Hundreds of residents of

that building, as well as people passing by on the street,

saw the drama unfold before their eyes. The quote at

the beginning of this paper is just one of many similar

comments newspaper and broadcast journalists recorded

that day. The experience of seeing someone die in real

life is not a common one for most people. But in film

and television fiction it happens frequently. When people see such a shocking event in reality it seems logical

that they confuse it with their familiar mediated experiences.

The most dramatic context for this category of

inverse-presence examples is the aftermath of the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks in New York. The first

author interviewed fellow journalists and members of

the public who witnessed the World Trade Center attacks firsthand when she covered the events for the

NBC television station WCAU in Philadelphia. She

heard more than one person make the Arnold Schwarzenegger comment at the beginning of this paper. Others commented that the scene looked like “a Spielberg

blockbuster.” A reporter on the scene that day wrote in

the New York Daily News, “The way people were running, it was like a scene out of ‘Godzilla.’” Another reporter said, “All I could think of was how much it was

like ‘The Blob,’ just this big mass coming at you”

(Goldiner, 2001). The first author remembers staring at

Manhattan’s skyline at 11 p.m. on September 11th and

thinking that there was no way the scene before her

could be real. Manhattan glowed not with the lights of

Broadway and skyscrapers, but with orange fire. With

the night sky so black and the fire so bright, she felt as if

she were in a movie theater watching the scene, not that

she was actually seeing a real event. Many members of

the journalistic corps discussed how if the real events

had been a summer movie, few would have believed it.

The first author also interviewed people who survived

the carnage in Manhattan. As they were brought into

the triage area, she was able to speak to those who

didn’t require medical treatment. The phrase they repeated was, “This can’t be real.” A woman who described seeing people jumping to their deaths compared

it to a horror movie she would never have chosen to

watch.

In the third category of inverse presence, people have

confusion concerning where mediated experience ends

and “real life” begins. Actors experience this “Reality

Show” phenomenon when they have the dual experience of playing a role that is duplicated in their offscreen life. Actor Bill Paxton appeared in a movie about

exploring the Titanic but he also did deep sea diving to

the wreck. “It was strange, because here I was doing

something in real life that I pretended to do in a film,”

Paxton said. “There were times when I was down there,

I thought (director) Jim (Cameron) was going to yell,

‘Cut!’ and we would go to lunch” (Cameron sails

back. . . , 2003). The almost seamless, even if momentary, confusion between diving for a movie role and diving “for real” makes this an example of an unusual and

perhaps extreme form of inverse presence. Actors and

other participants in mediated events, particularly those

that involve telling fictional stories, often must “become” another person, and in the process move back

and forth between (being present in) mediated and

nonmediated realities; the popular Method acting technique developed by Stanislavsky and Strasberg encourages actors to “live” a role (director John McGlynn

notes that “They’re not acting; they’re really there”;

Screen Actors Studio, 2003). It seems likely that this

makes them more susceptible to the illusions of both

presence and inverse presence. Actor Matt Dillon tells

the Philadelphia Inquirer, “I guess starting as an actor

at age 14, I always see the world as a movie” (Rea,

2003).

This susceptibility is unlikely limited to actors. Anyone can have a nonmediated experience that closely

mimics a familiar mediated one. A young soldier at boot

camp reflects on an intense experience he had as a raw

recruit: “Our CO dismissed us, we did an about-face

and everyone screamed ‘Ooh-rah!’ It was like a movie

496 PRESENCE: VOLUME 14, NUMBER 4

moment” (Military term causes. . . , 2003). Two of our

Web-survey respondents reported experiencing this type

of inverse presence. One describes a visit to Dallas,

Texas, and the grassy knoll made famous in President

Kennedy’s assassination. He explains that he had seen so

many movies and documentaries that when he actually

stood on the spot, “I felt like I was walking onto the set

of a TV show.” Another respondent remembers coming

out of high-presence movies and “for a few hours I was

not in my body at all, but in another plane in which I

hardly felt at all, or at least in a place where I could not

tell where my feelings ended and where the characters’

feelings began.”

4

A Definition

The phenomena revealed in the examples above

are clearly related to presence, and in many ways seem

to represent the reverse type of experience.

The explication of the presence concept by the International Society for Presence Research (2003) defines

presence, short for telepresence, as

A psychological state or subjective perception in

which even though part or all of an individual’s current experience is generated by and/or filtered

through human-made technology, part or all of the

individual’s perception fails to accurately acknowledge

the role of the technology in the experience. Except

in the most extreme cases, the individual can indicate

correctly that s/he is using the technology, but at

some level and to some degree, her/his perceptions

overlook that knowledge and objects, events, entities,

and environments are perceived as if the technology

was not involved in the experience.

The common element of the examples described

above can be stated, in contrast to this definition, as:

A psychological state or subjective perception in

which even though an individual’s current experience

is not generated by and/or filtered through humanmade technology, part or all of the individual’s perception fails to accurately acknowledge this. Except in

the most extreme cases, the individual can indicate

correctly that s/he is not using technology, but at

some level and to some degree, her/his perceptions

overlook that knowledge and objects, events, entities,

and environments are perceived as if the technology

was involved in the experience.

If (tele)presence is the illusion of nonmediation, then

inverse presence is the illusion of mediation. Two interrelated types of illusion of mediation can be identified,

one involving the form of experience and the other its

content. When an individual says something such as, “it

looked like a postcard” or “it felt like a movie,” they are

reporting similarities in the form of nonmediated and

mediated experiences, and confusion between the two.

When they suggest that the unfolding of events was

“like a movie” (i.e., scripted or artificial) they are pointing to similarities in (and confusion about) the content

of nonmediated and mediated experience. Ultimately,

when people experience presence they think (at some

level) that the mediated world is “real,” while when

they experience inverse presence, they think (at some

level) that reality is mediated. Inverse presence also

seems to frequently include the feeling that the experience is ephemeral and that there is a trigger somewhere

that will “turn off ” the movie or video game, at which

point the person will resume his or her real life. Lombard and Ditton (1997) define presence as “the perceptual illusion of non-mediation.” Therefore, inverse presence can be defined as the perceptual illusion of

mediation.2

5

A Theory of Inverse Presence

What causes inverse presence? The answer would

seem to lie with presence itself. Although it is likely in

part a function of our search strategy, the most common medium people mention when they describe in-

2

As Lombard and Ditton (1997) note, all experience is mediated

by our perceptual apparatus. The perceptual illusions of presence and

inverse presence refer to second-order mediation, or mediation by

human-made technology (International Society for Presence Research,

2003).

Timmins and Lombard 497

verse-presence experiences is film. And although presence has been identified in a wide range of media and is

thought to be most intensely experienced with sophisticated interactive simulations such as those generated in

virtual reality, the medium that in 2004 generates the

most frequent, intense experiences of presence among

the public is also film. The large-screen, high-resolution

images, high-fidelity and often multichannel sound, and

the darkened room of the movie theater, when combined with believable plot, dialogue, and acting, often

transport viewers into a movie’s world such that they

experience spatial and social presence. At the same time,

there are two characteristics of the nonmediated experiences that seem to evoke inverse presence: the experiences are compelling and idealized. And these are characteristics of movie experiences as well.

Many movies, and the experience of watching movies

in general, can reasonably be described as big, special,

dramatic, involving, engaging, powerful, intense, even

overwhelming—in short, good movies, at least, are

compelling. Movies also present not everyday reality but

a manufactured, idealized reality. With rare exceptions,

films focus on the peaks and valleys of life—not the dull

repetitive parts but the most unusual and interesting

events. And plots are devised and revised, scripts are

written and rewritten, scenes are recorded and rerecorded until every nuance is as the director envisions.

The result is a distilled, idealized reality, a sequence of

“perfect moments.” This sequence has a beginning,

middle, and end; viewers know that the event will be

“over” at some point. As with a TV program or VR, the

movie experience ends and real life reasserts its hold.

Most people then have experienced presence as they

visited compelling and idealized realities in the movie

theater. It seems logical to assume that when they have

an unusual, compelling, idealized (either positive or

negative) experience in their nonmediated life, they associate the nature of the experience with the perceptions

and emotions they’ve experienced in the movie theater.

They fall back on their memories, associations, and perceptions from familiar compelling and idealized movie

experiences to interpret what is happening. They feel

the sensations in nonmediated reality and at some level

associate them with, and perceive them as, a mediated

experience. The previous presence experience triggers

and accentuates the inverse-presence experience. The

limited duration of mediated experiences is transferred

to the new, nonmediated one as well—whether beauty

or tragedy, the person feels it is so unreal and unlikely

that it will suddenly end and “real life” will take over

again.

The range of events and experiences that can evoke

inverse presence is unclear, but as filmmaking and presentation (e.g., CGI and IMAX 3-D), virtual reality,

and simulation ride technologies evolve and become

more available to the public, the number and range of

presence experiences will likely increase, and the diversity of inverse-presence experiences should increase as

well.

A simple form of the more complex cognitive and

emotional phenomenon of inverse presence described

here involves the immediate perceptual aftereffects of

certain experiences mediated by technology. For example, in discussing research on the use of bifocal eyeglasses, Fitzpatrick (2004) notes that on first use,

“[t]here is a difference in what you perceive visually and

what your hand does when you go to reach for something.” After a time the brain adjusts to the new mediated reality (the world seen through the eyeglasses), but

when a subject removes the bifocals, the brain continues

to respond to the unmediated environment as if it were

still mediated, leading to the subject tripping or overreaching for objects. Similar perceptual aftereffects can

occur with virtual reality and other technologies. If you

stop using the bifocals or a simulator, for instance, you

continue to treat the nonmediated reality as you did

while you were wearing the glasses or were inside the

simulator. You may hold your head or walk in a certain

way that is not appropriate or useful outside the mediated situation. These aftereffects are immediate and

short-term as well as being more physiological, automatic, and universal than the examples above, but they

involve the same illusion of mediation. The other

inverse-presence examples are based on the cumulative

memories people have of mediated experiences.

Inverse presence as explicated here is also related to

other types of confusion between and among different

modes of experience. Most of us have had the odd ex-

498 PRESENCE: VOLUME 14, NUMBER 4

perience of not being able to remember whether an

event we recall actually occurred in our waking life or

only in a dream. Dream researcher Maurice MerleauPonty (1968) discusses the ways in which dreams inform waking reality:

Our waking relations with objects and others especially have an (unconscious) character as a matter of

principle; others are present to us in the way dreams

are and the way myths are, and this is enough to

question the cleavage between the real and the imaginary. (p. 48)

The effect, and likely the process, seems strikingly

similar to the examples of inverse presence above. One

news story quotes a Canadian lottery winner saying, “It

felt like a dream, like I might wake up at any moment”

(No great urge. . ., 2003). Again there’s more than just

a metaphor at work here; the person perceives a very

real nonmediated event as if it were mediated not by

technology but by their sleeping brain. As with other

inverse-presence examples, the words also describe an

ephemeral feeling, a sense that the real experience might

vanish like a dream does when we wake (or a movie

does when it ends).

French postmodern scholar Jean Baudrillard (1994)

theorizes about a mode of experience he calls hyper reality in which distinctions between reality and the unreality of images (simulations) and signs (simulacra) are

blurred. He suggests people create the reality they experience by using idealized models that have no connection to reality. “Unreality no longer resides in the

dream or fantasy, or in the beyond, but in the real’s hallucinatory resemblance to itself ” (Baudrillard, 1976, italics in original). Theorist Paul Virilio prefers the term

substitution to simulation: “[N]ew technologies are substituting a virtual reality for an actual reality. . . . We are

entering a world where there won’t be one but two realities. . . . One day the virtual world might win over the

real world” (Wilson, 1994). The increasingly sophisticated simulations and substitutions of hyperreality and

virtual reality can reasonably be expected to lead to confusions similar to both presence and inverse presence as

described here.

6

Potential Effects of Inverse Presence

As with most phenomena, inverse presence has the

potential for both positive and negative effects. Unfortunately, unlike presence itself, the potential for the latter seems to outweigh the former.

One positive effect of inverse presence may be its

function as a defense mechanism. Consumers of media

experiences can become desensitized or inured to violence or disaster when they see many portrayals of such

events. So if such a person is involved in a disaster in

real life, he or she may find the experience more familiar

and less threatening, and may recover more quickly.

The inverse-presence experience allows the person to

pretend, at least at some level, that the event is not real

and not “really” happening; because the event seems

like a mediated experience that is therefore not real, it

can serve to distance the person from, and help him or

her cope with, the unpleasant reality.

Despite this potential benefit, inverse presence can lead

to serious negative effects. Fortunately rare, the perception

that the nonmediated world one experiences is in fact mediated (and so not real) has led to tragically destructive

behavior. The two teenagers who killed their classmates at

Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado in 1999

left a video in which they indicated they were “following a

script they seem to have learned through the entertainment media—particularly from ultra-violent films and

video games” (Provenzo, 2000). Of course we can’t know

exactly how they felt as they killed their fellow students

and teachers, but speculation about the way they used media suggests that they may have experienced inverse presence. The “Matrix killers” offered as a defense that they

believed they were living in the film’s virtual reality and

that therefore shooting people didn’t really mean they

were killing them (Jackman, 2003).

In much less severe but probably more common

forms, inverse presence may lead to disappointments

and missed opportunities as reality that seems mediated

turns out not to be as compelling and/or idealized as

high-presence mediated experiences. For example, intense, high-presence experiences of media portrayals of

romance may lead women or men to approach romantic

situations in their real life as if they were media portray-

Timmins and Lombard 499

als, with the unrealistic expectations of a media-derived

script running in their heads. When a person perceives

reality at some level as mediated, he or she is likely to

believe that, as in most mediated portrayals, the “story”

will all work out right in the end. Arnold Schwarzenegger will stride through the city and kill the bad guys (or

rescue the government). The movielike lifestyle of parties and fairy-tale romance at the governor’s mansion

will continue “forever” for the “heroine” of the story. A

person who assumes that everything will work out may

fail to take the actions required to ensure that they do.

7

Studying Inverse Presence

The consideration of inverse presence here is exploratory and suggests the need for more systematic

research. Unfortunately, even compared to presence

itself the nature of inverse presence makes it difficult to

study. In addition to in-depth interviewing of those

who report having experienced inverse presence at some

point in their lives, researchers might create an environment in which “reality” bears the form and/or content

of a compelling and idealized mediated experience and

then study observers’ reactions. Such an experiment

would require that participants not be told about the

study or their participation in it in advance. For example, a dramatic chase (including running up escalators

and jumping from one floor to another) or a dramatic

conversation or argument between members of an attractive “movie star” couple could be staged at a shopping mall or other public space and interviews conducted with observers to see whether and how they

experienced inverse presence.

Rather than staging an experience, researchers might

take advantage of one that already exists. Researchers

could find a location of natural beauty, or one well known

from common mediated experiences (such as the site of

the Kennedy assassination) and interview passersby about

their reactions to the scene. A less pleasant prospect would

be to wait for a tragic event to take place and shortly thereafter talk to the people who saw it. A final possibility

would be to provide study participants with a compelling

mediated experience (e.g., an IMAX movie set in a distinc-

tive or exotic location) and then after a suitable interval

expose them to the same or a similar experience (e.g., take

them to the location or set the film producers used) and

interview them to see whether and how the latter experience evoked inverse presence.

8

Conclusion

Mediated experiences increasingly dominate our

lives. Movies and television already confuse the real and

the mediated. New technology is blurring the line further.

Video games and virtual reality are becoming increasingly

realistic. “Augmented reality” technology is on its way to

the public. Wearable computers will allow people to enter

a news story and see and feel the events the way the journalist who was there did (Mobile Augmented. . ., 2003),

and no doubt eventually we’ll be able to experience the

events live. As the line between real and mediated gets

harder to see, presence increases. An important and overlooked consequence of this trend is an increasing confusion from the other direction, in which “real life” seems to

be mediated. People will have more and more trouble distinguishing reality, and some may not even appreciate that

there is a difference. It will get harder for people to trust

their own senses and judgment and it will be more difficult

to impress people with nonmediated experiences. Some

people may see themselves as being at the mercy of larger

forces, like a character in a video game who can only do as

the player directs. And some may feel they can act as they

please because they or someone can push a game reset

button or start the movie over, so their actions will have

no lasting consequences.

We can argue that presence is a mostly positive result of

the world we live in today and that inverse presence is just

a relatively rare extension of presence. But as the trend

toward more presence and thus more inverse presence accelerates, we need to consider a larger concern about the

effect of inverse presence on how we perceive and experience our world. If people come to see real experience as

they do most media presentations, as “fake” or “planned”

or “set up” in some way, what experience will be perceived

as truly natural and organic rather than as contrived? In a

world of “pseudo-events” (Boorstin, 1961), we are already

500 PRESENCE: VOLUME 14, NUMBER 4

seeing the fake masquerading as the real; fake Christmas

trees, artificial flavorings and colorings, machines that

generate synthetic smells at the store and at home, lipsynching singers, virtual orchestras, and plastic surgery are

only the beginning. It’s only reasonable for us to become

more cynical, distrustful, and apathetic about the nonmediated world as the mediated world becomes more

dominant and inviting.

References

Baltzley, D. R., Kennedy, R. S., Berbaum, K. S., Lilienthal,

M. G., & Gower, D. W. (1989). The time course of postflight simulator sickness symptoms. Aviation, Space, and

Environmental Medicine, 60, 1043–1048.

Barrs, J., & Cabrera, C. (2002, November 2). Florida’s first

lady engages softer side of politics. The Tampa Tribune.

Available from: http://www.tampatrib.com.

Baudrillard, J. (1976). L’Echange symbolique et la mort. Paris:

Gallimard.

Baudrillard, J. (1994). Simulacra and simulation. Ann Arbor:

University of Michigan Press.

Bloom, C. (2003, February 27). Enjoy chance to make tracks

in snow. Available from: http://www.ohio.com/mld/

beaconjournal/living/5273879.htm.

Boorstin, D. (1961). The image: A guide to pseudo-events in

America. New York: Harper.

Cameron sails back to Titanic with Cannes film “Ghosts of the

Abyss.” (2003, May 18). Available from: http://famulus.

msnbc.com.

Chaffee, S. H. (1991). Communication concepts 1: Explication.

Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

David, W. (2003, October 2). Shooting of men by police

probed. The Journal News. Available from: http://

www.nyjournalnews.com.

Fitzpatrick, T. (2004, February 10). Researchers pinpoint

brain areas that process reality, illusion. Washington University in St. Louis Web page. Available from: http://

news-info.wustl.edu/tips/page/normal/652.html.

Goldiner, D. (2001, September 12). It’s so diabolical, so vicious. New York Daily News.

International Society for Presence Research (2003). What is

presence? Available from: http://www.temple.edu/ispr/

explicat.htm.

Jackman, T. (2003, May 20). Blame it on the Matrix. Avail-

able from: http://www.buffalonews.com/editorial/

20030520/1042361.asp.

Kasuba, E. (2003). “Apartment Fire.” Aired January 15, 2003

on KYW Newsradio 1060AM.

Lombard, M., & Bracken, C. C. (Eds.). (2003). Presence:

Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, 12(4).

Lombard, M., & Ditton, T. B. (1997). At the heart of it all:

The concept of presence. Journal of Computer-Mediated

Communication, 3(2). Available from: http://www.

ascusc.org/jcmc/vol3/issue2/lombard.html.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968). The visible and the invisible. (C.

LeFort, Ed.; A. Lingus, Trans.). Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Midland man travels world in Merchant Marine. (2003, May

24). Midland Daily News. Available from: from http://

www.ourmidland.com.

Military term causes a lot of hoo-ah. (2003, March 17). Contra

Costa Times. Available from: http://www.contracostatimes.com.

Mobile Augmented Reality Systems. Available from: http://

www1.cs.columbia.edu/graphics/projects/mars/mars.html.

No great urge to blow $10m. (2003, December 23). Vancouver

Province. Available from: http://www.vancouverprovince.com.

Packer, A. (2003, March 10). Crash involving two tour buses

injures dozens. Las Vegas Review-Journal. Available from:

http://www.reviewjournal.com.

Provenzo, Jr., E. F. (2000). Wellness journal: Protecting our

children from violence. Miami University Web site. Available from: http://www.miami.edu/veritas/feb2000/

benefit.html (2nd article).

Rea, S. (2003, May 11). Mixing menace, elegance in his debut. Philadelphia Inquirer. Available from: http://

www.philly.com.

Schexnayder, C. (2003, January 31). Veteran officer kills 21year-old. San Bernardino County Sun. Available from:

http://www.sbsun.com.

Screen Actors Studio (2003). SAS Overview: Method acting. Available from: http://www.screenactors.com.au/

overview.asp.

Steiner, L. (2004, December). Touching is believing. Pennsylvania Game News, pp. 45– 47.

U2. (1983). Sunday Bloody Sunday. On War [CD] Los Angeles: Island Records.

Want a good laugh? Try Blackhawks. (2003, March 10). Chicago

Daily Herald. Available from: http://www.dailyherald.com.

Wilson, L. (1994). Cyberwar, God and television: Interview

with Paul Virilio. Available from: http://www.ctheory.net/

text_file.asp?pick⫽62.