Paper:

advertisement

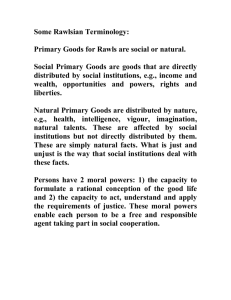

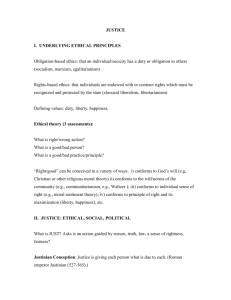

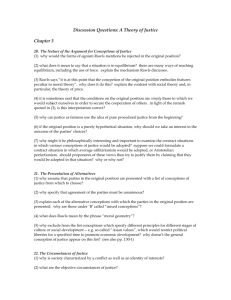

POLI 342: Modern Political Thought: John Rawls and his Critics Professor Michael Lakatos Paper: The Social Contract and its contentious role for Rawls’s “Theory of Justice” By Jan Kercher (International) SN: 11672037 Introduction In “A Theory of Justice” (Rawls, 1971), John Rawls tries to develop a conception of justice that is based on a social contract. His approach, doubtlessly, led to a revival of the contract theory in modern political theory. However, his peculiar conception of a hypothetical contract has also evoked a wave of severe criticism. Some of his critics settle for condemning special features of Rawls’s contractual concept, while others maintain that Rawls’s theory is, in effect, no real contract theory. In this paper, I will therefore focus on two research questions: Is Rawls’s theory a genuine contract theory at all? If yes, does the contract play a crucial role in this theory or is there a preferable alternative available to Rawls? The Rawlsian Social Contract I first want to briefly sketch the most important features of Rawls’s social contract. Far from giving a complete explanation of this highly complex conception, I will only focus on those features that are relevant for this paper. Rawls’s main idea is that the principles of justice are the object of an original agreement: “Thus, we are to imagine that those who engage in social co-operation choose together, in one joint act, the principles which are to assign basic rights and duties and to determine the division of social benefits” (Rawls, 1971, p. 11). However, this original agreement is not an actual historical contract, but only a hypothetical one (p. 12). The justification of the principles arising from the contract therefore depends on the notion that they would have been agreed to under the given theoretical and hypothetical conditions. In other words, the contract can be called “as-iffed” (Hall, 1957, p. 663). Rawls is convinced that true principles of justice can only be developed under fair conditions. This is why his theory is called “justice as fairness” (Rawls, 1971, p. 3). To reach this aim, i.e. to create fair conditions as a basis for the original agreement, Rawls constructs an “original position” of 1 equality. Though the original position “corresponds to the state of nature in the traditional theory of social contracts” (Rawls, 1971, p. 12) it is quite different in its composition. The desired equality of its inhabitants is reached through a “kind of complicated amnesia” (Sandel, 1998, p. 105) called the “veil of ignorance” (Rawls, 1971, p. 12). For our purposes, it is only important to know that this veil of ignorance leads to the fact that “no one knows his place in society, his class position or social status, abilities, his intelligence, strength, and the like” (Rawls, 1971, p. 12). Under the veil of ignorance, the parties of the original position are now facing a joint task: to agree on a contract that permanently fixes certain principles of justice which will be the basis for society once the veil of ignorance fades away. This procedure, in the end, leads to the two famous Rawlsian principles of justice (Rawls, 1971, pp. 11ff). For this paper, we can dispense with the actual content of these principles. More importantly, for our purposes, is to be sure about the peculiarity of Rawls’s contractual procedure. This procedure, namely, is hypothetical in a double sense: “It imagines an event that never really happened, involving the sorts of beings who never really existed” (Sandel, 1998, p. 105). Rawls’s theory - Not a genuinely contract theory at all? This first and most fundamental criticism maintains that Rawls, despite claiming so, does not produce a real social contract theory. This accusation is mainly related to three important features of Rawls’s theory: that his contract is purely hypothetical, that there is no state of nature in the theory, and that the contractors operate behind a veil of ignorance. For Ronald Dworkin, a “hypothetical contract is not simply a pale form of an actual contract; it is not a contract at all” (Dworkin, 1975, p. 18). As one can see, this criticism not only relates to Rawls’s theory: “it applies to the use of any hypothetical decision model in ethics” (Freeman, 1990, p. 135). The argument can be illustrated by the example of a poker game, in the middle of which the 2 two players find out that the deck is one card short. According to Dworkin, it is very unlikely that the losing player can convince the winning player to throw the hand in, even if he can convince the latter that both of them would have agreed to such a rule had the possibility of the deck being short been raised before the game. The same logic applies to those well-off in a society: Why should they accept rules that – based on a hypothetical contract – restrict their liberty by linking it to the benefit of the worst-off? As the contractors did not actually agree on it, the hypothetical contract seems to be non-binding and of no significance. Unfortunately, the self-evident solution to this dilemma, to replace the hypothetical contract with an actual one, is impossible. This would not only necessitate the remodelling of nearly all elements of Rawls’s original position, it would also rule out the justification of both principles of justice. As Rawls holds and Sandel shows, “actual contracts… cannot justify” (Sandel, 1998, p. 125) as they will always be afflicted with contingencies and conventions of some particular society. Another problem seems to arise from the veil of ignorance and the lack of a state of nature, two linked features that clearly distinguish Rawls’s theory from the classic social contract theories. To illustrate the problem, Hampton cites two essential features of contractual agreements developed by legal theorists: first, parties involved in them give promises, and second, contracts involve an exchange (Hampton, 1980, p. 324-5). The second feature, exchange seems to be problematic when applied to Rawls’s contract. The Rawlsian original position is not a state of nature, nor is the Rawlsian contract envisaged as an improvement on a state of nature. Therefore, the contractors are “not bargaining their way from a worse situation to a better” (Lessnoff, 1986, p. 141). Furthermore, Rawls even admits that the veil of ignorance leads to the fact that the “parties have no basis for bargaining in the usual sense” as “no one is in a position to tailor principles to his advantage” (Rawls, 1971, p. 139). By making the interests of all parties, in effect, identical, “we can view the choice in the original position from the 3 standpoint of one person selected at random” (Rawls, 1971, p. 139). Therefore it seems that there is hardly anything to exchange. The veil of ignorance simply “rules out the making of a contract based on an exchange of considerations” (Hampton, 1980, p. 327). This even leads Schaefer to the claim that Rawls’s parties in the original position are “not human beings at all… they are unreal, purposeless, lifeless ciphers, unanimous in their anonymity” (Schaefer, 1974, p. 103). Sandel (1998, p. 122-32) comes to a similar ascertainment: despite Rawls’s claims (Rawls, 1971, pp. 28-9), the contract lacks two vital characteristics, namely plurality (of distinct individuals) and choice. It seems that the (identical) parties merely have to acknowledge principles already there1. Consequently, this leads to a conclusion similar to that of Dworkin: “What goes on in the original position is not a contract after all, but the coming to self-awareness of an intersubjective being” (Sandel, 1998, p. 132). How can Rawls’s theory be defended against such major accusations? Considering Dworkin’s objection, Rawls (in his response) maintains that a heuristic view of the agreement in the original position can solve this dilemma (Freeman, 1990, p. 135)2. It is thus seen as “a thought experiment designed for purposes of self- and political clarification” which “helps us understand what the combined force of certain generally accepted intuitive ideas and firmly held moral convictions that shape public reasoning commits us to” (Freeman, 1990, p. 135). Furthermore, Rawls’s hypothetical contract does not seem very problematic if we come to see that it serves in an evaluative rather than a legitimizing role. “The contract is envisaged as a test of the desirability and feasibility of the arrangement” (Kukathas/Pettit 1990, p. 27). So Rawls does not really need an actual contract for this (limited) purpose. Regarding the second objection, Lessnoff shows that bargaining is hardly a feature of all classic social contract theories: “Rather, each theory simply posits its own conclusions 1 “The relevant agreement is not to enter a given society or to adopt a given form of government, but to accept certain moral principles” (Rawls, 1971, p. 16, emphasis added) 2 This role of Rawls’s contract is also emphasized by Kukathas/Pettit (1990, p. 27ff). 4 as the ‘obvious’ outcome of the contract, presumably optimum for all contractors” (Lessnoff, 1986, p. 141-2). In comparison to these classic theories, Rawls’s contract is even superior as it makes the exclusion of bargaining intelligible after all. Furthermore, not all contracts or agreements are like economic bargains. There are also agreements “to tie down the future, to keep the parties from later changing their minds and deviating from the shared norms or purposes of the association” (Freeman, 1986, p. 143). A good example can be found in the application of quality management. Employer and employee conclude a contract that fixes the goals of the employee for the next year. Though there is no real exchange involved, the contract provides stable and shared expectations, which benefits both parties. What is important therefore, is not an exchange that is fixed by the contract, but the outcome of the contract itself. Finally, given the desire to maximize control over the same primary social goods, which are limited in supply, the parties in the original position may even have conflicts of interest. And they certainly have a choice, although Rawls’s terminology is certainly unfortunate in many passages referring to this choice. Thus, it is clear that there is a list of different conceptions of justice between which the contractors have to choose (Rawls, 1971, p. 1226). That they all choose the same principles is not a consequence of the fact that there is no real choice but a consequence of the condition of fairness and the finality of the agreement3. Therefore, a contract between identical individuals does not have to be a contradiction: “Many identical individuals are still many individuals” (Lessnoff, 1986, p. 142). The role of Rawls’s contract – crucial or dispensable? Even if we take the contract postulated by Rawls as a genuine contract, given the arguments of its defenders illustrated above, it might still have a very weak or even dispensable role in his argument. As already mentioned, the original position is not a state of nature. Instead, Rawls defines it as a 3 I will discuss this interrelation more detailed in the next section. 5 state of fairness between the parties (Rawls, 1971, pp. 11ff). Fairness, however, is a matter of moral judgements. “Hence the original position both reflects certain moral judgements or principles, and is supposed to yield (via the contract) certain moral principles (the principles of justice)” (Lessnoff, 1986, p. 142). According to some critics4, these two sets of moral principles are essentially the same. This charge includes another school of criticism, namely that Rawls manipulates his contractual argument in an arbitrary and question-begging way5. Thus, the notion of the contract seems to play no role at all in the choice of the two principles of justice, it is simply superfluous. Schaefer therefore sees the main reason for Rawls’s use of the contract metaphor as a simply “rhetorical one” (Schaefer, 1974, p. 103). If there was no contract to agree to, the parties would nevertheless come to the same conclusion. This criticism, however, does not seem very convincing. It is hard to imagine how the parties in the original position would come to an agreement without the finality of the contractual agreement. Rawls mentions this finality repeatedly and explicitly: “Since the original agreement is final and made in perpetuity, there is no second chance” (Rawls, 1971, p. 176)6. That, in turn, creates “strains of commitment” (Rawls, 1971, p. 176) for the design of the principles of justice. The parties know that they have to stick to their agreements after the veil of ignorance is lifted; therefore, they all opt for principles that they can commit to in the actual society. This, in turn, leads to an agreement on the two principles of justice. Thus, the importance of the contract to create a sense of finality seems obvious. However, even this argument is an aim of criticism. According to Hampton, “there is a constraint operating already in the original position, independent of anything following from the contract requirement” (Hampton, 1980, p. 330). What Hampton refers to are the formal constraints of the concept of right. These are the conditions that 4 Similar criticisms can be found in: Honderich, 1975, pp. 68-70; Carr, 1975, pp. 87-8 Unfortunately, a closer look at this type of criticism would go beyond the scope of this paper. 6 See also p. 12 p. 145 5 6 Rawls imposes on the conceptions of justice “that are to be allowed on the list presented to the parties” (Rawls, 1971, p. 130). The fifth condition is the condition of finality. As Rawls remarks, “the parties are to assess the system of principles as the final court of appeal in practical reasoning. There are no higher standards to which arguments in support of claims can be addressed” (Rawls, 1971, p. 135). That means that the condition of finality is already included in the formal constraints of the concept of right. Though this constitutes a different form of finality, namely the finality of the conception of justice selected and not the finality of the selection itself, it nevertheless creates something similar to the “strains of commitment”, something that Hampton calls the “strains of finality” (Hampton, 1980, p. 333). In conclusion, this, once again, would mean that contractual situation and non-contractual situation have the same outcome. However, in a next step, Hampton goes even further and maintains that Rawls’s contract would even have a worse outcome if instituted without the finality constraint of the concept of right. The finality constraint of the concept of right could do without the contract, but the contract could not do without the finality constraint of the concept of right. How does Hampton come to this puzzling conclusion? She asserts that the contractual agreement is not necessarily irrevocable: “each of them knows that if he finds the consequences of a justice conception’s application too distasteful once he has resumed his place in society, he might be able to convince the others to renegotiate the contract” (Hampton, 1980, p. 332). However convincing the rest of Hampton’s argument7, this last step does not seem to be maintainable. Hampton obviously treats Rawls’s contract as an ordinary (actual) contract: “Insofar as the making of a contract is voluntary, the ending of it is voluntary as well” (Hampton, 1980, p. 331). For such an ordinary contract, her arguments might be right. But they certainly misinterpret Rawls’s conception of the contract. Rawls’s contractors know that the contract they are agreeing to 7 Unfortunately, I did not have the space to elaborate on all of Hampton’s arguments here. Thus, I focused on those arguments that I regarded as relevant for the purpose of this paper. 7 is not temporary: “a group of persons must decide once and for all what is to count among them as just and unjust” (Rawls, 1971, p. 12). Furthermore, the whole conception of the original position with the veil of ignorance only makes sense if the contract reached in this condition is final. Why should Rawls’s contractors make a contract at all in the original position if they could change it immediately after the veil of ignorance fades away? Once again, we should remind ourselves of the interpretation of the contract as a “thought experiment” (see above). Once a person has (voluntarily) entered this thought experiment and therefore the (hypothetical) original position, he has at the same time accepted that the contract has to be final. Otherwise, he simply would not have entered into the original position8. A last word may be said to Hampton’s charge that, according to Rawls, the original-position procedure can be repeated to see whether a new justice conception would be preferred to the two principles of justice (Hampton, 1980, p. 331)9. Despite Hampton’s claims, there seems to be no contradiction between the irrevocability condition and the possibility to repeat the hypothetical contract. Again, it has to be said that Rawls’s conception has to be seen as a heuristic tool to find a notion of justice. This tool can obviously be used repeatedly without defeating its purpose (as long as the conditions in the original position are fair, a fair conception of justice will be reached); but only if the finality of the agreement is made clear (otherwise, there could be no agreement). Although this finality does not have to be instituted by a contract, there seems to be no reason why it “cannot” be (Hampton, 1980, p. 324). 8 The motivation to enter the original position is, once again, an aim of Rawls’s critics (see for example Dworkin, 1975). Again, a satisfying discussion would go beyond the scope of this paper. 9 The first and most obvious problem with Hampton’s claim is that such a statement by Rawls cannot be found in the section that Hampton cites (Rawls, 1971, § 21). I consider her claim nonetheless as she cites § 21 only as “for example” (Hampton, 1980, p. 331). Nevertheless, her argument still loses power through this citation mistake. 8 Conclusion As argued above, I do not think that the cited critics succeed in showing that Rawls’s theory is not a contract theory at all. In the way Rawls uses his contract, it seems to be a useful tool to justify his two principles of justice. Another question is, however: Does Rawls depend on the contract, or is there an alternative available to him that is maybe equally or even better suited for this purpose? Here, I think Hampton succeeds in showing that a there is in fact a viable alternative. As Hampton does not introduce a term for this alternative, I will refer to it as the “final choice” procedure10. Two virtues seem to support such a final choice. First, it seems to resemble Rawls’s notion of a “unanimous choice” (Rawls, 1971, p. 140) in the original position. In this regard, it seems even more adequate than the contract tool. Second, it can be instituted without greatly changing Rawls’s theory. As Hampton shows, the finality is already given by another feature of Rawls’s conception; therefore, it would be possible to maintain Rawls’s theory and dismiss the contractual conception at the same time: “the contract is not as indispensable in Rawls’s theory as it appears under some interpretations” (Kukathas/Pettit, 1990, p. 63). Does that mean that Rawls is really “confused about the logic of his own thought” (Hampton, 1980, p. 332)? To answer this question, it seems helpful to look at the reasons that Rawls himself gives us for using a contract theory. These are: the explanation of a conception of justice by a theory of rational choice (1), the clarification of the plurality (2) and publicity condition (3), as well as the tie to the tradition of the contract doctrine (4) “which helps to define ideas and accords with natural piety” (Rawls, 1971, p. 16). Interestingly, Rawls makes no secret of the fact that he partly uses the contract as a rhetorical device. It seems, however, that this is the only function that can be exclusively and satisfactorily fulfilled by a contract. A rational choice, even more articulate, is also inherent in Hampton’s tool of the final choice procedure. The publicity condition is already 10 A similar alternative, though less detailed, is introduced by Alexander (1974, pp. 604-5): “After all, it is the choosing, not the agreeing, that is critical” (p. 604). 9 instituted in the third formal constraint of the concept of right (Rawls, 1971, p. 133). The plurality condition, finally, as shown above, cannot be satisfactorily clarified by the contract. Given the “principle of simplicity” (Alexander, 1974, p. 604), it then seems reasonable to drop the redundant contract feature. However, I have my doubts. To me, the heuristic virtue of Rawls’s contract is a crucial feature of his theory. I doubt that a final choice procedure has the same heuristic strength, however attractive it may be for other reasons. I also do not agree that dropping Rawls’s contractual procedure is the only solution to the redundance problem. Why not, instead, drop the finality constraint of the concept of right? A convincing argument that dropping one of the essential features of Rawls’s theory is really the most desirable solution to the discussed problems has to include a procedure that also compensates for the high intelligibility of Rawls’s conception. Finally, I do not think that there really is a redundance problem. Quite the contrary: I see the contract as a useful procedure to point out and – at the same time – operationalize the constraints of the concept of right, which would otherwise seem to be arbitrarily chosen. As Kukathas/Pettit (1990, p. 64) put it: “The constraints of the concept of right give expression to the idea that any [conception of right] must be such that its implementation would involve the rule of law… The main role of the contractual device is to keep this fact vividly before our minds”. 10 Bibliography Alexander, Sidney S. (1974). Social Evaluation Through Notional Choice. In The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 88, No. 4, pp. 597-624. Carr, Spencer D. (1975). Rawls, Contractarianism and Our Moral Institutions. In The Personalist, Vol. 56, pp. 83-95. Dworkin, Ronald (1975). The Original Position. In Reading Rawls: Critical Studies on Rawls’ A Theory of Justice. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. Freeman, Samuel (1990). Reason and Agreement in Social Contract Views. In Philosophy and Public Affairs, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp. 122-57. Hall, Everett W. (1957). Justice as Fairness: A Modernized Version of the Social Contract. In The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 54, No. 22, pp. 662-70. Hampton Jean (1980). Contracts and Choices: Does Rawls Have a Social Contract Theory?. In The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 77, No. 6, pp. 315-38. Honderich, Ted (1975). The Use of the Basic Proposition of a Theory of Justice. In Mind, Vol. 84, No. 333, pp. 63-78. Kukathas, Chandran / Pettit, Philip (1990). Rawls: A Theory of Justice and its Critics. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. Lessnoff, Michael (1986). Social Contract. London: Macmillan. Rawls, John (1971). A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. Sandel, Michael J. (1998). Liberalism and the Limits of Justice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Schaefer, David Lewis (1974). A Critique of Rawls’ Contract Doctrine. In Review of Metaphysics, Vol. 28, pp. 89-115. 11