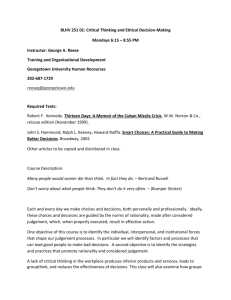

Strategic Decision Making Process: The Role of Management and

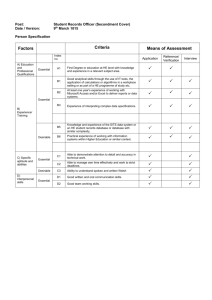

advertisement