Inoculating Consumers Against “Unconscionable” Business Practices

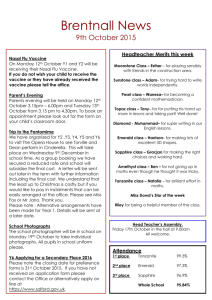

advertisement