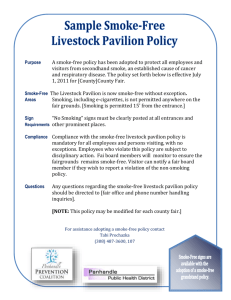

smoke-free policies an action guide

advertisement