Embeddedness. - University of Michigan

advertisement

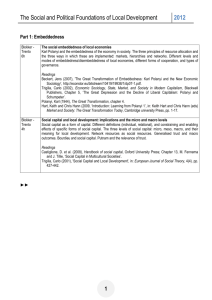

EMBEDDEDNESS Maxim Sytch Ross School of Business University of Michigan 701 Tappan St. Ann Arbor, MI 48109 Ph: 734.763.6822 Fax: 734.764.2555 msytch@umich.edu Yong Hyun Kim Ross School of Business University of Michigan 701 Tappan St. Ann Arbor, MI 48109 Ph: 734.709.2522 Fax: 734.764.2555 yonghyun@umich.edu Traditionally, the concept of “embeddedness” is attributed to Hungarian scholar Karl Polanyi, who suggested that economic actions and social relationships are deeply intertwined. He proposed that, on the one hand, the economic system is embedded in the social system, stating “...whatever principle of behavior predominated in the economy, the presence of the market pattern was found to be compatible with it [the social system]” (Polanyi 1944: 68). On the other hand, he argued that in a contemporary market economy “…social relations are embedded in the economic system” (Polanyi 1944: 57). An implication of Polanyi’s embeddedness is that social actors were no longer viewed as autonomous, valuemaximizing actors focused exclusively on economic gains. Instead, they became actors that were also concerned with their social standing and social assets (e.g., Polanyi, 1944: 46). As a result, the idea of embeddedness was novel in that it constituted a sharp departure from the basic principles of classic economics, which at the time dominated the analysis of markets and economic action. Broadly defined, the idea of economic action being intertwined and interdependent with the broader social context—and thus “embedded”—can be traced to the writings of numerous influential sociologists, including Gouldner (1954), Selznick (1957), and Stinchcombe (1965). For example, Selznick documented that the emergence of the social structure in an organization might help infuse the rational production system with “value beyond the task at hand” (Selznick, 1957: 17). Similarly, Gouldner (1954) documented that people placed a lot of value of friendship and kinship ties in a work setting and that workers chose those jobs so that they could remain close to their families. In large part due to its broad, encompassing nature and inherent ambiguity, the concept of embeddedness remained dormant and underused in empirical research until Mark Granovetter published his seminal work in 1985. Granovetter (1985) reframed the notion of embeddedness with a significantly greater degree of precision, conceptualizing the idea as a patterning of economic actions by networks of social relationships among actors. An inherent attraction of this argument is the delicate middle ground between the “undersocialized” view of an atomized actor in classical and neoclassical economics and the “oversocialized” view of an agency-free actor in structural-functional sociology. This delicate balance is accomplished by strongly emphasizing the role of “concrete personal relations and structures (or “networks”) of such relations” (Granovetter 1985: 490) in guiding economic action and outcomes. By providing greater conceptual clarity for the term embeddedness itself and linking the concept to networks of social relationships, Granovetter’s work created an actionable platform for subsequent empirical investigations. Beginning in the mid-1980s, a significant body of empirical research has investigated the notion of embeddedness, leading some scholars to label the idea as “the basic unit of analysis” in new economic sociology (Swedberg, 2001: 1990). One of the earliest and classic empirical investigations using the lens of embeddedness (even preceding Granovetter’s [1985] seminal article) was conducted by Wayne Baker (1984) who conceptualized the national stock options market as a network of relationships among traders. Baker identified that the sociostructural patterns of trading, in turn, significantly affected the price volatility of the traded financial instruments. Scholars have used the lens of embeddedness and have carefully analyzed networks of relationships among individual and corporate actors to explain a range of economic actions and outcomes, including company survival and financing decisions (e.g., Uzzi, 1996, 1999); the choice of interorganizational partners and governance choices (e.g., Gulati, 1995a,b); as well as the diffusion of governance practices (e.g., Davis & Greve, 1997). Among some of the promising developments in embeddedness research are (1) a deeper understanding of embeddedness at a dyadic relational level (e.g., Uzzi, 1997; Gulati & Sytch, 2007); (2) understanding the role of exact structural properties of ego-networks, network communities, and global network structures in shaping economic outcomes (e.g., Burt, 1992; Rowley et al., 2004); and (3) recognizing the co-evolution and co-dependence of the networks of collaboration and conflict in shaping actors’ behaviors and outcomes (e.g., Sytch & Tatarynowicz, 2013). REFERENCES Baker, W. E. 1984. The social structure of a national securities market. American Journal of Sociology, 89(4): 775-811. Burt, R. S. 1992. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Davis, G. F., & Greve, H. R. 1997. Corporate elite networks and governance changes in the 1980s. American Journal of Sociology, 103: 1-37. Gouldner, A. W. 1954. Patterns of Industrial Bureaucracy. Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press. Granovetter, M. 1985. Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3): 481-510. Gulati, R. 1995(a). Does familiarity breed trust? The implications of repeated ties for contractual choice in alliances. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1): 85-112. Gulati, R. 1995(b). Social structure and alliance formation patterns: A longitudinal analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(4): 619-652. Gulati, R., & Sytch, M. 2007. Dependence asymmetry and joint dependence in interorganizational relationships: Effects of embeddedness on exchange performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 52: 32-69. Polanyi, K. 1944. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Boston: Beacon Press. Rowley, T., Baum, J., Shipilov, A., Greve, H. R., & Rao, H. 2004. Competing in groups. Managerial and Decision Economics, 25: 453-471. Selznick, P. 1957. Leadership in Administration: A Sociological Interpretation. Evanston, IL: Row, Peterson, and Company. Stinchcombe, A. L. 1965. Social structure and organizations. In J. G. March (Ed.), Handbook of Organizations: 142-193. Chicago: Rand McNally. Swedberg, R. 2001. Max Weber's vision of economic sociology. In R. Swedberg, & M. Granovetter (Eds.), The Sociology of Economic Life: 77-95. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. Sytch, M. & Tatarynowicz, A. 2013. Friends and foes: The dynamics of dual social structures. Academy of Management Journal: Forthcoming. Uzzi, B. 1996. The sources and consequences of embeddedness for the economic performance of organizations: The network effect. American Sociological Review, 61(4): 674-698. Uzzi, B. 1997. Social structure and competition in interfirm networks: The paradox of embeddedness. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42: 35-67. Uzzi, B. 1999. Embeddedness in the making of financial capital: How social relations and networks benefit firms seeking financing. American Sociological Review, 64: 481-505.