best laid plans.qxp - University of Glasgow

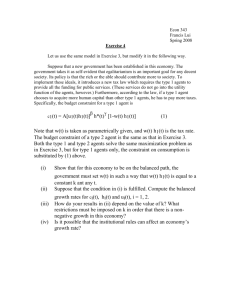

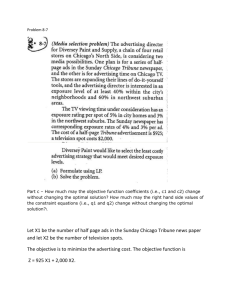

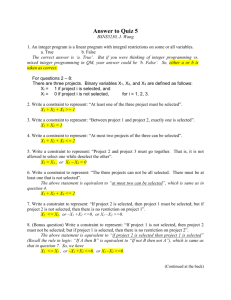

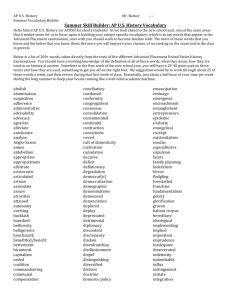

advertisement