2. Formation of the contract a) Agreement

advertisement

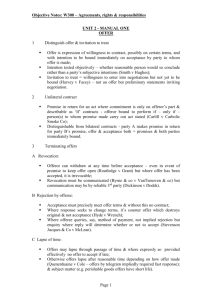

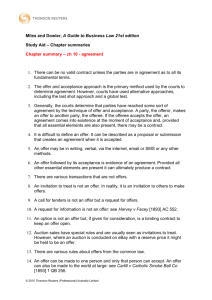

18 2. Formation of the contract Case for discussion (Gibson v Manchester City Council [1979] 1 W.L.R. 294) Council houses are built and operated by local councils to supply homes on secure tenancies at affordable (below market) rents to the local population. When the Conservative Party was governing, Manchester City Council started selling council houses to long-term tenants. G was one of the tenants eligible under this scheme. He informed the council of his interest in buying his house. The Council replied by letter stating: “The corporation may be prepared to sell the house to you at the purchase price of £2,725 less 20 per cent. = £2,180 (freehold)." G was told that if he wanted "to make formal application" to buy his council house he should complete and return the enclosed application form. G completed and returned the form. Before the Council could reply, the Labour Party won the next elections and immediately stopped selling council houses. Does G have a claim for specific performance, i.e. for transfer of the property in the house? a) Agreement Contract = legally enforceable agreement • • agreement = consensus ad idem, meeting of minds between the contracting parties However, the law is not concerned with minds but with conduct of parties Æ objective approach to agreement, subjective expectations and unexpressed mental reservations are ignored (compare §§ 133, 157 BGB, difference between both legal systems: few possibilities of rescinding the contract (Anfechtung) in English law, see below at II 4) • • • Chief Justice Brian (1478): "The intent of a man cannot be tried, for the devil himself knows not the intent of a man." Lord Denning, Storer v Manchester City Council [1974] 3 All ER 824 at 828: "In contracts you do not look into the actual intent of a man's mind. You look at what he said and did. A contract is formed when there is, to all outward appearances, a contract." Contracts are generally concluded by offer and acceptance and must be intended to be legally binding. Offer • • • = proposal or promise by one party (offeror) to another party (offeree) to enter into a contract on a particular set of terms with the intention of being legally bound need not be made to specific party, may be made to group of persons or the public at large (example: Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co, [1892] 2 QB 484 – contractual offer rather than unilateral promise as in § 657 BGB) distinction offer – invitation to treat, test: Does the statement show a willingness to be bound if the other party expresses agreement? Lehrstuhl Zivilrecht VIII Prof. Dr. Ohly Introduction to English Law 19 - • • • The use of the word "offer" or statement of a price is not in itself decisive. The advertisement of goods for sale is generally not regarded as offer (example: Fisher v Bell [1961] 1 QB 394, discussed above at I 3), but exceptionally an advertisement can be couched in terms which will be regarded as an offer, see Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co) The display of goods and the indication of a price is normally an invitation to anyone to make an offer. Hence contracts in self-service shops are usually concluded at the check-out counter (see Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v Boots Cash Chemists [1953] 1 QB 401). auctions: auctioneer invites offers from bidders which he can either accept or reject: see s 57(2) Sale of Goods Act 1979: "A sale by auction is complete when the auctioneer announces its completion by the fall of the hammer, or in the customary manner; and until the announcement is made any bidder may retract his bid." Offer can be made in writing, orally or by conduct. The offer must be communicated to the other party. Termination of offer: revocation before acceptance: An offer can be withdrawn at any time before acceptance, even if explicitly left open (reason: requirement of consideration), withdrawal must be communicated to offeree (if communicated by letter, the letter must actually reach the other party), communication by third person sufficient death of offeree before acceptance or death of offeror (1) if offeree has been informed about the death or (2) in case of personal offer. rejection by offeree lapse of offer = non-acceptance within prescribed period or within reasonable time (see Ramsgate Victoria Hotel Company Limited v Montefiore (1865-66) LR 1 Ex 109: reply in November to offer for purchase of shares made in June = unreasonable delay) Acceptance • • • • = unconditional agreement to the terms of the offer with the intention of being legally bound Can be expressed in writing, orally or by conduct. If method of acceptance has been indicated by the offeror acceptance should be conveyed in this manner. Must be communicated to other party, silence does not amount to acceptance (Felthouse v Bindley (1862) 11 CB (NS) 896 (CP)). The requirement of notification can be waived (example: Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co) on two conditions: waiver by offeror, overt act or conduct by offeree which is evidence of an intention to accept. Lehrstuhl Zivilrecht VIII Prof. Dr. Ohly Introduction to English Law 20 • • • • Acceptance by post: offer only takes effect when it reaches the other party the acceptance, however, takes effect once the letter is posted, even if it never reaches the other party ("mailbox / postal rule"), see Adams v Lindsell, Re London & Northern Bank [1900] 1 Ch. 220. The postal rule will not apply where the letter of acceptance has not been properly posted, where the letter is not properly addressed, where the express terms of the offer exclude the postal rule or where it is unreasonable to use the post. Possibilities of justifying the postal rule analytically: (1) The offeror can secure himself by requiring actual notification. (2) The rule is a pragmatic way of limiting the possibilities of revocation. (3) In the event of delay or loss, the offeror is more likely to enquire about what has happened. Open questions: (1) Is there a binding contract, if the acceptance is posted but never reaches the offeror? (2) Can a postal acceptance been withdrawn by speedier means? instant communication (face-to-face negotiations, telephone conversations) acceptance must actually be received by offeror, however, contract binding where offeror fails to receive the message through his own fault, see Entores v Far East Co Open question: are e-mail communications to be treated as postal or as instant communications? When contract are made by interaction with a website the position has been affected by the Electronic Commerce (EC Directive) Regulations 2002 (see materials). The battle of the forms • • • An offer must be absolute and unqualified: acceptance under different conditions is counter-offer which amounts to rejection of the first offer Battle of the forms: offeror includes his standard terms, offeree accepts, including his standard terms Possibilities (see Butler Machine Tool Co Ltd v Ex-Cell-O Corporation) - consequent application of the above-mentioned rule = "final shot" approach, see British Road Services v Arthur V Crutchley [1968] 1 Lloyd's Rep 271 - application of article 19 (2) CISG: “(2) However, a reply to an offer which purports to be an acceptance but contains additional or different terms which do not materially alter the terms of the offer constitutes an acceptance, unless the offeror, without undue delay, objects orally to the discrepancy or dispatches a notice to that effect. If he does not so object, the terms of the contract are the terms of the offer with the modifications contained in the acceptance.” Lehrstuhl Zivilrecht VIII Prof. Dr. Ohly Introduction to English Law 21 b) Intention to create legal relations Intention to create legal relations • • • Not all agreements are enforceable. When A invites B for dinner and B offers to bring a bottle of wine A will not be able to claim performance or damages if B appears without the wine. Main test for seriousness = consideration (see below, 3), but additional test: For there to be a valid contract, the parties must have intended to create legal relations. The test is an objective one. Commercial arrangements • • General presumption that commercial arrangements are enforceable. exceptions: advertising puffs = hyperbolic statements which will not be taken seriously by the recipient ("The world's best restaurant"), but see Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co gentlemen's agreements, if clear evidence exists that the agreement was supposed to be unenforceable, see Rose and Frank Co v Crompton (JR) & Bros Ltd [1925] AC 445 letters of comfort, see Kleinwort Benson Ltd v Malaysia Mining Corp Sdn Bhd [1989] 1 All ER 785 Social and domestic arrangements • • c) General presumption that social and family arrangements are not enforceable Balfour v Balfour [1919] 2 KB 571 Jones v Padavatton [1969] 1 WLR 328 Simpkins v Pays [1955] 1 WLR 975 problem: agreements between husband and wife during marriage, on separation or between de facto spouses, see Merritt v Merritt [1970] 2 All ER 760: agreement between spouses on separation that husband will transfer title to the family home if wife pays off the mortgage is binding. Contracts requiring a specific form General rule: A contract does not require a specific form in order to be valid • • In exceptional cases, however, a specific form is prescribed by statute or common law. possibilities: contract made by deed contract made in writing contract evidenced in writing Lehrstuhl Zivilrecht VIII Prof. Dr. Ohly Introduction to English Law 22 Contracts which must be made by deed • • - Deed = under common law instrument made in writing, sealed and delivered to other party, Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989, s. 1: seal no longer required for deeds executed by individual, if document in writing, signed in presence of a witness, delivered to other person. required for purchase of a freehold in land lease of more than three years (if only made in writing, the contract will be valid in equity as between the parties, but not at law as against third parties) articles for partnerships gratuitous promises Contracts which must be made in writing • • - = contract void unless made in writing required for disposition of an interest in land bills of exchange, cheques, promissory notes hire-purchase contracts and other consumer credit contracts transfer of shares in a registered company assignment of copyright Contracts which must be evidenced in writing • • = contract not made in writing is valid, but unenforceable required for contracts for the sale of land contracts of guarantee contracts of employment Lehrstuhl Zivilrecht VIII Prof. Dr. Ohly Introduction to English Law