Dramatic Devices & Structure

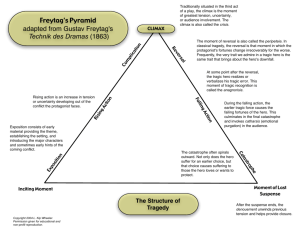

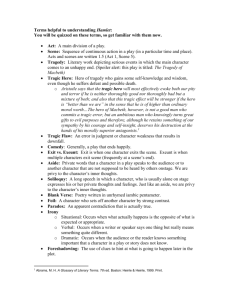

advertisement

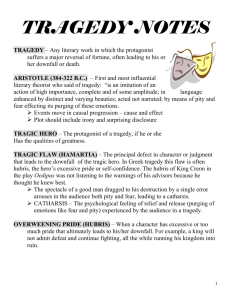

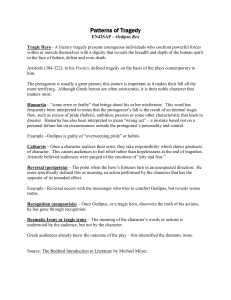

Dramatic Devices Irony: The recognition of reality different from appearance. It is easily confused with sarcasm, but it is less harsh. Its presence may be marked by a sort of grim humour and “unemotional detachment”, a coolness in expression at a time when one’s emotions appear to be really heated. Characteristically, it speaks words of praise to imply blame and words of blame to imply praise. Verbal Irony is when one character intentionally says something with a meaning that another character is not aware of – the actual intent is expressed in words that carry the opposite meaning. Situational Irony - Sometimes a situation is ironic (different from what it appears or what was intended to be) in which some of the actors on stage or some of the characters in a story are blind to the facts known to the spectator or reader. Dramatic Irony – The words or acts of a character may carry a meaning unperceived by the character but understood by the audience. Usually the character’s own interests are involved in a way that he or she cannot understand. The IRONY resides in the contrast between the meaning intended by the speaker and the different significance seen by others. Tragic Irony – The form of dramatic irony in which a character uses words that mean one thing to the speaker and another to those better acquainted with the real situation, especially when the character is about to become a tragic victim of fate. Double Entendre A statement that is deliberately ambiguous, one of whose possible meanings is risqué or suggestive of some impropriety (a single word that has more than one meaning - double meaning. One of the meanings is indecent). Pun A play on different words that that happen to sound alike. Theme: The central idea/purpose of the story. It can be a message or lesson that the author has for the reader. Motif: Motifs are recurring structures, contrasts, or literary devices that can help to develop and inform the text’s major themes. Monologue: A composition giving the discourse of one speaker. By convention, a monologue represents what someone would speak aloud in a situation with listeners, although they do not speak; the monologue therefore differs somewhat from the soliloquy, which represents what someone is thiking inwardly, without listeners. Suspense: A technique uses by writers to create a feeling of anxious uncertainty about the outcome of events. Foreshadowing: Occurs when the author gives the readers hints about the events which will occur later in their works. It is an important device that the author uses to create suspense and to prepare readers for upcoming incidents. Symbols: An object, an action, or a person that are representative of a larger meaning related to the story’s theme. Satire: A work or manner that blends a censorious attitude with humour and wit for improving human institutions or humanity. When a narrator uses sarcasm and wit to expose the folly or idiocy of another character we call it satire. Sarcasm: A caustic and bitter expression of strong disapproval. Sarcasm is personal, jeering, intending to hurt. Expressionism: An anti-naturalistic movement chiefly associated with Germany after World War I. . . . Expressionism does not seek to "hold the mirror up to nature" or to present reality dispassionately; rather, it seeks to show the world as we feel (rather than literally see) it. Imagery: Descriptive writing that uses the senses to paint a picture in the reader’s mind. The use of words that appeal to the 5 senses (hearing, seeing, smelling, tasting and touching) in order to express a certain idea. It may be perceived through literary description, allusion, or in the secondary references of its similes or metaphors. Tragedy: A tragedy is a drama in which the central character or characters suffer disaster or great misfortune. In many tragedies, the downfall results from fate, a serious character flaw, or a combination of the two. Other contributing causes may be present as well. The Greek philosopher Aristotle defined tragedy as “an imitation of an action that is serious, complete, and of a certain magnitude.” He explained that although the main character is noble, a tragedy must focus on action rather than on character development. The action should arouse feelings of pity and fear in the audience. The theme of a tragedy is the meaning of the central idea or insight about life that explains why the downfall occurred, as well as the main character’s recognition of that meaning and its consequences. Tragic Hero: A hero that has potential for greatness but is doomed to fail. He can be trapped in a situation where he cannot win or he can have some tragic flaw that causes his fall from greatness Fate: Fate is the intervention of some force over which human beings have no control Domestic Tragedy: Tragedy dealing with the domestic life of commonplace people – fate at work among the ordinary. Modern Tragedy: Until the close of the seventeenth century almost all tragedies were written in verse and had as protagonists men of high rank whose fate affected the fortunes of a state. The eighteenth century saw the development of a drama, known as bourgeois or domestic tragedy, which was serious but superficial. It was written in prose, and presented a protagonist from the middle or lower social ranks who suffers a commonplace or domestic disaster. With the emergence of Ibsen in the late nineteenth century came the concept of middle-class tragedy growing out of social problems and issues. In the twentieth century middle-class and labouring-class characters are often portrayed as the victims of social, hereditary, and environmental forces. When they receive their fate with a self-pitying whimper, they can hardly be said to have tragic dimensions. But when, as happens in much modern serious drama, they face their destiny, however ill and unmerited, with courage and dignity, they are probably as truly tragic, mutatis mutandis, as Hamlet was to Shakespeare’s Londoners. Anachronism: An anachronism is an event or a detail that is inappropriate for the time period. For example, a car in a story about the Civil War would be an anachronism; cars had not yet been invented. In a play set in the 1920’s, the word nerd would be an anachronism because nerd wasn’t used as slang until much later in the 20th century. Dramatic Structure: A tragedy will show the following divisions, each representing a phase of the dramatic conflict. The structure is based on the analyogy of the tying and untying of a knot. Exposition (Protasis) The introduction creates the tone, gives the setting, introduces the characters (and their relationships to one another), supplies other facets necessary to the understanding of the play, such as the events in the story supposed t have taken place before the part of the action included in the play, since the play is likely to plunge in MEDIA RES, “into the midst of things”. Exciting Force Also called the complication or the initial incident. This is what gets the action going. It is the beginning of the conflict in the play. Rising Action or Complication The series of events that led up to the climax of the play comprise of the rising action. These events provide a progressive intensity of interest for the audience. The rising action involves several acts in the play. Climax or Crisis (Exciting Force through to the Crisis is called the Epitasis) This represents the turning point for the play. From this point onwards, the hero moves towards his inevitable end. Falling Action (Catastasis) This includes those events from the climax up to the hero’s death. The episodes will show both advances and declines in various forces acting upon the hero. Like the rising action, the falling action will involve events in more than one act. Stresses the activity of the forces opposing the hero, and although some suspense must be maintained, the trend must lead logically to the disaster with which the tragedy is to close. It is set in movement by a single event called the tragic force, closely related to the climax and bearing the same relation to the falling action as the exciting force does to the rising action. The latter part of the falling action is sometimes marked by an event that delays the catastrophe and seems to offer a way of escape for the hero. This is the moment of “final suspense” and aids in maintaining interest. The falling action, ususally shorter that the rising action, is often attended by some lowering of interest because new forces must be introduced and an apparenently inevitable end made to seem temporarily uncertain. Relief Scenes are often resorted to, partly to mark time, partly to provide emotional relaxation for the audience. The Catastrophe The catastophe marks the tragic fall, usually the death, of the hero, comes as an unavoidable outgrowth of the action. It satisfies not so much by a gratification of the emotional sympathies of the spectator as by its logical conformity and by a final presentation of the nobility of the succmbing hero. A “glimpse of restored order” often folloes the catastrophe in a Shakespearean tragedy.This concerns the necessary consequences of the hero’s previous actions which must be the hero’s death. The catastrophe will naturally be simple and brief.