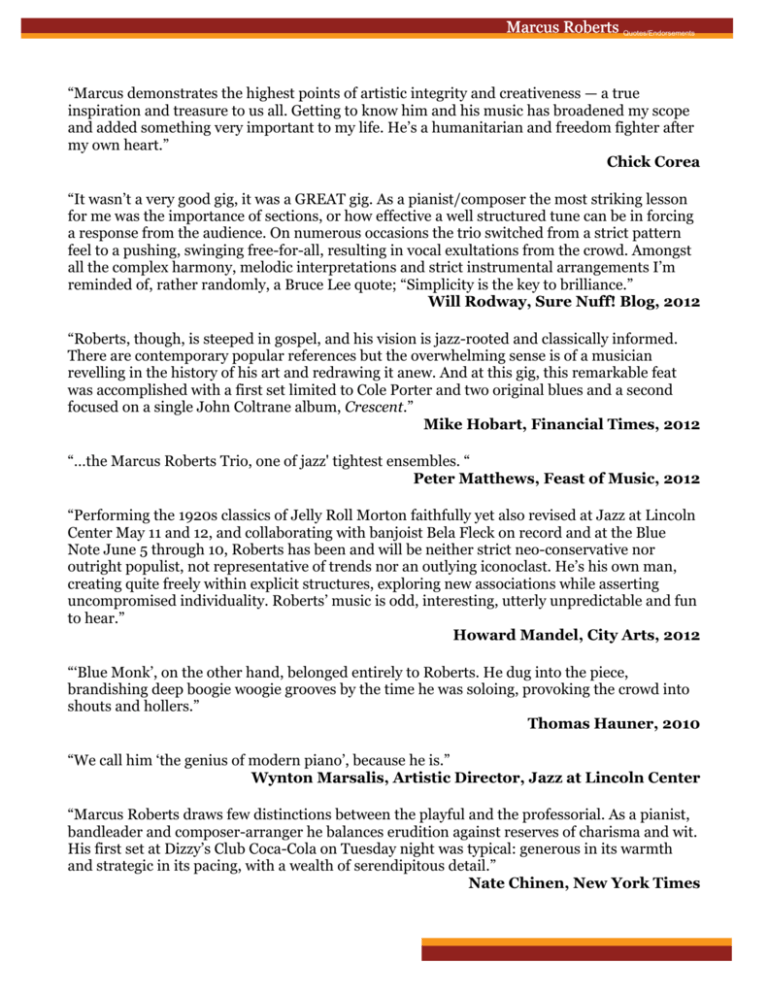

Marcus Roberts 4XRWHV(QGRUVHPHQWV

“Marcus demonstrates the highest points of artistic integrity and creativeness — a true

inspiration and treasure to us all. Getting to know him and his music has broadened my scope

and added something very important to my life. He’s a humanitarian and freedom fighter after

my own heart.”

Chick Corea

“It wasn’t a very good gig, it was a GREAT gig. As a pianist/composer the most striking lesson

for me was the importance of sections, or how effective a well structured tune can be in forcing

a response from the audience. On numerous occasions the trio switched from a strict pattern

feel to a pushing, swinging free-for-all, resulting in vocal exultations from the crowd. Amongst

all the complex harmony, melodic interpretations and strict instrumental arrangements I’m

reminded of, rather randomly, a Bruce Lee quote; “Simplicity is the key to brilliance.”

Will Rodway, Sure Nuff! Blog, 2012

“Roberts, though, is steeped in gospel, and his vision is jazz-rooted and classically informed.

There are contemporary popular references but the overwhelming sense is of a musician

revelling in the history of his art and redrawing it anew. And at this gig, this remarkable feat

was accomplished with a first set limited to Cole Porter and two original blues and a second

focused on a single John Coltrane album, Crescent.”

Mike Hobart, Financial Times, 2012

“…the Marcus Roberts Trio, one of jazz' tightest ensembles. “

Peter Matthews, Feast of Music, 2012

“Performing the 1920s classics of Jelly Roll Morton faithfully yet also revised at Jazz at Lincoln

Center May 11 and 12, and collaborating with banjoist Bela Fleck on record and at the Blue

Note June 5 through 10, Roberts has been and will be neither strict neo-conservative nor

outright populist, not representative of trends nor an outlying iconoclast. He’s his own man,

creating quite freely within explicit structures, exploring new associations while asserting

uncompromised individuality. Roberts’ music is odd, interesting, utterly unpredictable and fun

to hear.”

Howard Mandel, City Arts, 2012

“‘Blue Monk’, on the other hand, belonged entirely to Roberts. He dug into the piece,

brandishing deep boogie woogie grooves by the time he was soloing, provoking the crowd into

shouts and hollers.”

Thomas Hauner, 2010

“We call him ‘the genius of modern piano’, because he is.”

Wynton Marsalis, Artistic Director, Jazz at Lincoln Center

“Marcus Roberts draws few distinctions between the playful and the professorial. As a pianist,

bandleader and composer-arranger he balances erudition against reserves of charisma and wit.

His first set at Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola on Tuesday night was typical: generous in its warmth

and strategic in its pacing, with a wealth of serendipitous detail.”

Nate Chinen, New York Times

Marcus Roberts 5HYLHZV

January/February 2014

Marcus Roberts:

"All Kinds of Things"

At 50, the pianist is as resourceful and ambitious as

ever (By Michael J. West)

“We were talking, the [Jazz at Lincoln Center] Orchestra, about who

we consider to be a genius,” laughs Wynton Marsalis. “I said

someone was a genius and cats were laughing at it. So I said, ‘All

right, then, who do you consider a genius?’ And the cats said,

‘Marcus Roberts.’”

If anyone is aware of Roberts’ brilliance, it’s Marsalis; after all, he first

Marcus Roberts (photo by John Douglas)

made his mark in the trumpeter’s band from 1985 to 1991. Ask

Roberts, though, and he’s simply a hard-working artist, even if his profile on the jazz landscape isn’t what it once was, despite efforts

like his 2012 disc with Béla Fleck, Across the Imaginary Divide, and the nonet recording Deep in the Shed: A Blues Suite, released that

same year. “To some folks it may have appeared like I haven’t been doing a lot over these last years,” the pianist and composer, 50,

says on the phone from his home in Tallahassee. A native Floridian, Roberts is a jazz studies professor at Florida State University.

“Maybe the sense was that I was just walking my dog every day at 5 o’clock and wasn’t really doing much. But quite to the contrary, I’m

always working—on all kinds of things.”

“All kinds of things” is right. Last April, on the 45th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s death, Roberts premiered a piano concerto

dedicated to King with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. Then, in November, he released three albums: From Rags to Rhythm, a 12-part

suite, and two reunion albums (both recorded in 2007) with Marsalis, Together Again in the Studio and Together Again Live in Concert.

These are ambitious projects, too. Each of the concerto’s three movements is based on an analogous one by a classical composer, but

the piece also explores components of the blues (chords, rhythm, improvisation). Though the Marsalis records—both performed with

Roberts’ longtime trio, Rodney Jordan on bass and Marsalis’ younger brother Jason on drums—are titled such that they suggest the

same music presented in two contexts, in fact they’re entirely different set lists; the studio record includes five Roberts originals and

three standards, while the live one is all standards. They also call for the musicians involved, especially the trumpeter, to employ all

aspects of their respective techniques. From Rags to Rhythm, again performed with the trio, is not just a conceptual suite but a thematic

one: It’s built on five short motifs that comprise the suite’s opening, shape many of its melodies and serve as sectional cues within the

movements.

More ambitious still, Roberts edited and produced everything for release on his own J-Master label—no small feat, given that the pianist

has been blind since childhood. He was able to do so by virtue of a software package called Job Access With Speech, or JAWS. The

program works with the onscreen visual display that sighted people use, but interprets its information and relays it to the user with a

digital speech interface. “Just learning that technology, that took a couple years of work. It’s finally matured to the point where you really

can do serious editing on your own,” says Roberts. Just exploiting this functionality, he adds, is important. “I feel like I’m kind of a

representative of the disabled community in general, and certainly the blind community—I have a responsibility to use this technology to

show that a blind person can do it.”

It’s a rather ultramodern undertaking from a pianist whose reputation is that of a neo-traditionalist, noted for his blues and stride chops

as well as for tributes to players like Jelly Roll Morton. But Roberts disputes that characterization. “I don’t know when that started or

what that really means. Certainly I love early piano and consider it important, but I hadn’t even heard Jelly Roll Morton’s music until I

was 26 or 27 years old!” he chuckles.

“What I am a proponent of,” Roberts adds, “is a dialogue with the history of jazz, and to showcase its relevance right now, today. If you

have a chef who cooks you a meal that’s based on a 350-year-old recipe, if you’re hungry, and you eat the food, and it tastes great, are

you going to say, ‘Well, no, I don’t want that because it’s too old?’ You’re probably gonna say, ‘Have you got more of it back there?’”

Indeed, for all the early jazz feel in much of Roberts’ music, it has always engaged with bebop and postbop as well. His piano-trio

conception, for example, involves the instruments interacting on a democratic level, à la Bill Evans. That sensibility, and other

modernisms, can be heard in his new releases as well: From Rags to Rhythm is very much in a postbop milieu, and even the live

standards with Marsalis include “Giant Steps” alongside “When the Saints Go Marching In.”

Is Roberts a genius? That’s unknowable. But his combination of talent, ambition, discipline, stylistic openness and resourcefulness

suggest that he is a remarkable musician—perhaps even a phenomenon, another sort of which Marsalis can’t resist comparing him to.

“When the Lincoln Center Orchestra plays with him,” he says, “cats look like they seen a ghost, he’s playing so much stuff.”

© © 1999–2014 JazzTimes, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

http://jazztimes.com/articles/117596-marcus-roberts-all-kinds-of-things

Marcus Roberts 5HYLHZV

Music roundup: Marcus Roberts gets

his '60 Minutes.' Be part of it

Written by Mark Hinson, Democrat senior writer | Aug. 1, 2013

Each time jazz icon Wynton Marsalis performs at FAMU or Florida State,

he stops the concert for a few minutes to lavish praises on his friend,

pianist and FSU jazz professor Marcus Roberts.

The two have known each other since the ‘80s when Roberts landed the

job of playing piano with the Wynton Marsalis Septet. Later, Roberts

embarked on a career of his own.

When Marsalis was in town on Feb. 8 for a concert with the Jazz at

Lincoln Center Orchestra as part of this year's Seven Days of Opening

Nights arts festival, he told the sold-out crowd, essentially, that they

would be crazy to miss Roberts' upcoming tribute to Jelly Roll Morton at

Seven Days.

"The man (Roberts) is a genius," Marsalis said and then repeated it two

or three more times to make sure he was getting his point across.

Backstage after the concert, Marsalis continued to remark on Roberts' talent: "The man is a genius intellectually, spiritually and musically. He is

completely innovative. He has invented another way to play the jazz piano. Marcus is like a movement. Years from now, people will look back on all the

students and piano players that he influenced and it will become known as the School of Marcus Roberts. People shouldn't take him for granted just

because he lives here (in Tallahassee). He is a genius."

Usually, you have to die to get anyone to say something that nice about you.

This fall, Marsalis plans to make his case to a much larger audience when he profiles Roberts for a segment on the television news magazine “60

Minutes.” Marsalis, who works as a cultural correspondent for CBS, and the “60 Minutes” crew are taping Roberts on camera in Jacksonville, St.

Augustine and Tallahassee during August.

“I'm fascinated to see how they put the whole piece together,” Roberts said. “They also did a long interview with Chick Corea. I have no idea how much

of anything they'll use.”

The cameras will be rolling and Tallahassee jazz fans can get in on the act when the Marcus Roberts Trio performs at 8 p.m. on Aug. 28 at the intimate

B Sharp’s Jazz Cafe, 648 W. Brevard. The group will perform an original suite that Roberts composed for Chamber Music America in 2001. The B

Sharp’s show will carry a cover charge but no price has yet been set. Stay tuned to Limelight for ticket details.

On Aug. 29, Roberts and an assortment of special guests called The Modern Jazz Generation will play for the “60 Minutes” profile piece in Ruby

Diamond Concert Hall. The program is titled “Romance, Swing, and the Blues.” That concert is free and open to the public.

“I want to get a good house for that show,” Roberts said on Monday night. “I want to fill up the place with a big crowd. It’s going to be a good show, I

guarantee that.”

Roberts said he thinks Marsalis decided to shine the “60 Minutes” spotlight on him after the Marcus Roberts Trio presented the world premiere of his

original “Spirit of the Blues: Piano Concerto in C minor” with the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and at the Savannah Music Festival in early April.

(Judging from the performance that I saw in Atlanta, the piano concerto is a melodic showpiece that easily puts Roberts on a par with composer-pianist

George Gershwin.)

“I think that’s what convinced Wynton,” Roberts said.

The piano concerto was also quite an achievement for a composer-musician who lost his eyesight at the age of 5 while he was growing up in

Jacksonville. It took Roberts, who turns 50 next week, a lifetime to write his first piano concerto because "the notation technology on my computer had to

catch up," Roberts said.

"It (the piano concerto) about kicked my (bleep)," Roberts said of the writing process. "I studied Beethoven intimately. I studied Ravel, Bartok. I really

had to break it down."

In the meantime, Roberts is getting ready to launch a Kickstarter campaign to help finance the recording of an album being made with the 12-member

Modern Jazz Generation. The lineup of players includes drummer-vibraphonist Jason Marsalis (younger brother of Wynton), bass player Rodney Jordan,

trombonist Ron Westray and trumpet player Marcus Printup. Keep an eye on www.kickstarter.com or visit Roberts’ page on Facebook for more.

Copyright © 2013 www.tallahassee.com. All rights reserved.

http://www.tallahassee.com/article/20130801/ENT/308010054/Music-roundup-Marcus-Roberts-gets-his-60-Minutes-part-it

Marcus Roberts 5HYLHZV

Marcus Roberts 5HYLHZV

A night of sheer talent: Béla Fleck and the Marcus Roberts Trio

March 30, 2011 | Jordan Wannemacher

Bela Fleck and Marcus Roberts Trio delivered an energetic set

I can now say for the rest of my life that the most amazing thing I’ve ever done on a Tuesday was go see Béla Fleck and the

Marcus Roberts Trio at Charles H. Morris Center during the Savannah Music Festival of 2011.

Béla Fleck, one of the greatest banjo players of all time (and inarguably one of the most versatile) performed with the Marcus

Roberts Trio on March 29. There was no shortage of sheer genius talent among the trio either. Marcus Roberts, an extremely

multifaceted jazz artist, played piano alongside Jason Marsalis on drums and Rodney Jordan on bass.

The venue was extremely intimate and had a beautiful stage set up. The acoustics were incredible, and being that close to the

band, you really felt like you had them playing in your own living room. It was the perfect setting for a night of jazz.

While normally I’m accustomed to the banjo being used for bluegrass music, it was refreshing to hear banjo jams to jazz

music. The banjo is not ordinarily the first instrument to mind when it comes to jazz, but wow does it sound amazing. The

blend between sounds was beautifully harmonious.

Although the evening begun with jazz music, Béla and the trio quickly mixed it up to keep things interesting. Béla and Marcus

played a ragtime duet and then later all four played a bluegrass blended jam that was reminiscent of some of Béla Fleck’s

older experiments with the banjo. I really enjoyed that they covered so many genres of music in their 75 minute set. The

diversity in their music choices really demonstrates the eclecticism of each musician’s abilities.

The performance was absolutely breathtaking. The talent exhibited in these four musicians was outstanding. Each musician,

successfully displaying each of their outstanding individual talents, packed the performance with riveting solos. The audience

excitedly applauded after each one, and by the end everyone was starting to dance a bit in their seat; the rhythm was truly

contagious.

The Trio kept remarking on how much fun they were having performing together which really made it exciting for the

audience and added to the intimacy of the moment. They really connected with the packed audience.

People came to Savannah from all over to experience the Savannah Music Festival. The couple to my right at the concert had

come all the way from Canada, mainly to be there that very evening.

After the 6 p.m. show, Béla joked with the Trio, “Hey that was fun, let’s do it again real soon.” They did, of course, have

another performance at 8:30 p.m. Béla also performed earlier in the afternoon at Kennedy Pharmacy on Broughton Street.

Marcus Roberts 5HYLHZV

Chicago Tribune

JAZZ REVIEW: Roberts meets Basie: A dynamic debut at Symphony Center

Howard Reich Arts critic; hreich@tribune.com

April 24, 2011

Until Friday night, pianist Marcus Roberts and the Count Basie Orchestra never had performed together. But you

wouldn't have known it by the premiere of their collaboration at Symphony Center, which appears to have marked

the start of a beautiful relationship.

Separately, of course, each half of this duo has a great deal to recommend it.

Roberts stands as one of the most imposing pianists of the under-50 generation, his encyclopedic knowledge of

jazz-piano history matched by a formidable technique and a keen ear for instrumental color.

The Legendary Count Basie Orchestra (its grandiloquent full name) far transcends the notion of a "ghost band,"

the pejorative term used for ensembles that soldier on long after their leaders have fallen. As the unit's previous

concerts have attested, the Basie organization retains a great deal of the blues-swing spirit that defined the

original, even if it lacks a measure of the stylistic flair that Basie himself directed from the piano chair.

Still, no one knew for sure whether Roberts' trio and the Basie players could find common musical ground. They

managed to do so, however, from the opening notes, in part thanks to Roberts' exquisite sense of taste and

hyper-virtuoso pianism.

It fell to Roberts, after all, to hold the position once occupied by Basie, but Roberts declined to mimic the master.

Instead, he offered his own galvanic approach to the keyboard in up-tempo pieces and a heightened tonal

sensitivity in ballads. Even when he was conspicuously referencing Basie keyboard gestures, Roberts

embellished and redefined them. His trio – staffed by bassist Rodney Jordan and drummer Jason Marsalis – gave

considerable rhythmic lift to the proceedings.

In Neal Hefti's arrangement of "The Kid from Red Bank," which opened the Roberts-Basie portion of the program,

the pianist's tone glistened during solos and somehow cut through the orchestral texture in ensemble passages.

And in Sammy Nestico's orchestration of the somewhat pulpy "Sweet Georgia Brown," Roberts' succinct lines and

unusual, angular motifs very nearly brought the old warhorse into the 21st century.

But it was in Roberts' originals that the pianist – and the band – reached the evening's artistic high point.

Roberts wrote "Evening Caress" for his chamber suite "Romance, Swing and the Blues" (1993), and his

orchestration of the vignette showed the glorious idiosyncrasies of his writing (including sinuous instrumental

counterpoint). The rhythmic drive of the work, as well as Roberts' propulsive way of expressing it, made this a

most tempestuous "Caress."

Better still, Roberts' "Athanatos Rhythmos" inspired gorgeously lush keyboard solos and the most audacious,

hard-driving orchestral playing of the night. The piece sounded practically like a movement of a jazz piano

concerto, auguring well for the full-scale concerto Roberts has been commissioned to write for his trio and the

Atlanta Symphony Orchestra (to be premiered next year).

Nowhere on this program did the Basie Orchestra, conducted by Dennis Mackrel, make as vivid an impression as

it did with Roberts. In effect, a fine jazz ensemble reached higher in the presence of its guest, while the pianist

surely benefited from the gales of orchestral sound sweeping around him. They ought to take this show on the

road.

Marcus Roberts 5HYLHZV

Savannah Music Festival review: Bela Fleck and the Marcus Roberts Trio

BY BILL DAW ERS ON MARCH 30, 2011 · IN MUSIC

Bela Fleck and Marcus Roberts have been spoiling Savannah Musical Festival audiences for years now.

Fleck, perhaps the world’s most important banjo player, seems to have found a second home with the SMF: 2011

marks his fifth appearance in the last six years. Most notable to me was Fleck’s Africa Project with Toumani Diabate,

D’Gary, and Vusi Mahlasela in 2009. Jazz pianist and educator Roberts has been a regular too since 2003; he also

serves as the SMF’s associate director for jazz education.

Given the SMF’s incredible history of supporting collaboration, maybe it was only natural that Fleck would

eventually find himself on stage at the Morris Center performing amidst Roberts’ amazing trio, which includes

drummer Jason Marsalis and bassist Rodney Jordan. Then again, how often do musicians take risks like this, trying

to meld instruments and styles in such daring ways?

I loved the 75 minute set I saw last night before a packed house of 300. It was clear from the first moments that

Fleck and Roberts could make the banjo and the piano speak to each other, especially with the higher notes, which

were complemented further by Marsalis’ cymbals.

Fleck and the Marcus Roberts Trio had obviously spent a lot of time working together, but there was still an

improvisational, what’s-going-to-happen-next feeling to the entire show. Before tackling a new composition by

Fleck, Roberts briefly noted that jazz musicians love improv, but when he first heard the piece, he wondered: “How

do we play this?”

After a stunning rendition of “Lullaby of Birdland” near the end of the show, Fleck picked up a microphone: “I’ve

never been terrified in such a friendly way before.”

As rich and unpredictable as the sound was from the foursome, I think the best moments were ones when the piano

and banjo were paired most closely. For Joplin’s “Maple Leaf Rag,” Marsalis and Jordan left the stage, leaving Fleck

and Roberts to get as much as they could from the ragtime classic. I don’t know, btw, if any of this work could be

truly marketable, but any future work between Fleck and Roberts should include ragtime — it’s a style that seemed

especially fitting to the jangliness of the banjo and quick precision of Roberts’ piano.

The piano and banjo also played off of each other especially beautifully in Roberts’ composition “A Servant of the

People” off the album Blues for the New Millenium.

Roberts paid special thanks to SMF director Rob Gibson, whom he has known for about 20 years, for “creating a

space where we could do something like this.”

So what next? I’m sure both artists will listen closely to the audio recorded by the SMF last night. I’m sure they’ll

both continue other projects. I’m sure they’ll stay in touch and almost certainly meet again here in Savannah. But

maybe they won’t wait that long and will find time to continue to explore the music. I hope so — I’d love to see what

Fleck and Roberts could do with a more sustained collaboration.

Marcus Roberts Reviews

Marcus Roberts, London Jazz Festival

By Mike Hobart

Published: November 19, 2009 23:11 | Last updated: November 19 2009 23:11

On Monday, American Marcus Roberts’s all-acoustic set at Wigmore Hall was delivered with pin-drop dynamics,

and his repertoire – Jelly Roll Morton to Thelonius Monk and a bundle of Cole Porter – was locked in jazz

tradition. Roles were more fluid, with bassist Rodney Jordan having freedom to roam and initiate.

Yet there was overlap. Themes were starting points for dialogue that rarely ended up in the same place – sudden

accelerations, counterpoints and odd time signatures were just some of the surprise twists – and the sparse beats

of drummer Jason Marsalis were full of contemporary edge and implication. This is an organic trio, but Roberts

stood out. He is a flawless, soulful improviser, and his second set encore, a slow, note-hanging blues, capped a

magical concert.

Financial Times (www.FT.com)

Marcus Roberts 5HYLHZV

San Francisco Examiner

Marcus Roberts Concert Review, Examiner.com

https://www.examiner.com/jazz-in-san-francisco/piano-ace-marcus-roberts-delights-sfjazz-show

Piano ace Marcus Roberts delights in SFJAZZ show

x

March 18th, 2011 10:48 am PT

Some jazzbos will tell you that once a pianist masters

stride, the physically demanding boogie-woogie/ragtime

offshoot pioneered by Fats Waller and others,

everything else is easy.

It was easy to accept that watching Marcus Roberts

perform Thursday in an SFJAZZ concert at Yerba

Buena Center. Roberts, an early cohort of Wynton Marsalis, nailed stride technique

when he was in his 20s and has gone on to conquer a comprehensive chunk of jazz

tradition.

And do it with misleading ease, as evidenced by his bravura performance Thursday.

Stride poses particular challenges to the left hand, and Roberts has drawn from that

strength to create a distinctive style that melds rhythmic power and certainty with a

melodic touch that finds inherent drama in dynamic extremes.

Drawing from a repertoire of standards, jazz nuggets, originals and surprise or two -Who would have figured the somewhat traditionalist Roberts as a devotee of banjo

iconoclast Bela Fleck -- the pianist covered a wide swath of jazz tradition and emotional

territory.

Highlights included a gossamer reading of John Coltrane's "Naima" with an impressive

spiderweb effect -- you marveled that anything could be so light and yet so strong. A

wander through Thelonious Monk's "Light Blue" started with a similarly delicate effect

but evolved into a grand cascade of chords that impressed with both the speed and

assurance of Roberts' fingering.

The pianist's New Orleans sentiments were on delightful display in a romp through

"What is This Thing Called Love" flavored with just the right touch of New Orleans street

march and rollicking boogie-woogie workout on "Country Blues."

Roberts also highlights the value of working with a steady crew of supporting players.

Bassist Rodney Jordan and drummer Jason Marsalis (brother of Wynton, Branford, et

al) beautifully complemented Roberts' sensibilities, with Marsalis in particular showing a

remarkably varied dynamic touch.

Marcus Roberts 5HYLHZV

The sounds of Christmas are upon us!

21st November 2011 · 0 Comments

By Geraldine Wyckoff

Contributing Writer, Louisiana Weekly

Marcus Roberts Trio

Celebrating Christmas

(J-Master Records)

Marcus Roberts is known for his ability to maximize jazz traditions with his unique approach

and use of forward-striving musicians in his trio settings. On Celebrating Christmas, the pianist,

who first gained recognition on the jazz scene playing and recording with trumpeter Wynton

Marsalis, takes on a package full of the best-known Christmas standards. He and his trio with

longtime member drummer Jason Marsalis and bassist Rodney Jordan, deliver the classics with

respect for the familiar melodies — all are recognizable — and jazz sensibilities.

Marsalis kicks off “Jingle Bells” with great verve that is soon followed with equal liveliness by

Roberts” piano mastery. It”s a toe-tapper, a revelry of rhythm that certainly dashes through, if

not the snow, the rush of the ride.

On the other hand, “Silent Night” finds pleasure and drama through its starkness and slow

tempo. Jordan”s big, warm bass notes fill the soulful peace of the song. As is often the case in

Roberts” work, the pianist plays a duel role on this song and throughout the album. His

powerful, left-handed chords underlie the improvisational fluidity of his right hand. It”s almost

as if hearing two separate players.

A few tunes, like “Frosty the Snowman,” are short, cheerful little ditties. Meanwhile, the trio

really takes off on “The Twelve Days of Christmas” that has, especially rhythmically, never

sounded quite like — or as good — as this. It staggers, it swings, it pauses and reflects. “Winter

Wonderland” receives equally inventive treatment swinging like crazy. Marsalis provides a

totally unexpected drum solo that comes from another realm yet, somehow, fits. The

wonderland of Christmas meets the African continent in Marsalis” tone and attitude.

Naturally, Marsalis is also out front on “Little Drummer Boy.” An interesting aspect of this tune

is that he plays a march-like drum cadence throughout the song. Meanwhile Roberts stays true

to the familiar melody — often with great elaboration — in a seemingly unrelated rhythmic

fashion that nonetheless works.

Celebrating Christmas with the Marcus Roberts Trio offers the opportunity to enjoy the

traditional songs of the holiday spiced with fine jazz performed by masters. It”s at once homey

and sophisticated and well-suited for a family gathering or a champagne and caviar fete.

Marcus Roberts 5HYLHZV

The Marcus Roberts Trio at Ronnie Scott’s

Posted on March 24, 2012

by Will Rodway , Sure Nuff! Blog

Bit of a delay with this, it’s been a hectic week. I find it strange that I haven’t found one other review of this 2 night residency (although I

suspect there will be quite a few for the Ambrose Akinmusire gig on the 26th). Maybe Robert’s style is lacking the media ‘buzz’ factor, or I

could just be looking in all the wrong places. If it’s the latter and anyone knows of one I’d be interested to read it.

I have to admit it took some effort to haul myself to Ronnie’s last Monday. ‘T was a long ol’ day and the last thing I needed was being plonked

amidst a potentially noisy audience drowning out the sweet stage sounds. However I’d pre-paid (Ronnie’s is not cheap, you know?) and in

these times of austerity I thought it’d be a crime not to appease my initial motivations.

Ah, but the music. If I was open to being lured by one swinging oasis on a drizzly Monday night then surely the Marcus Roberts Trio at

Ronnie’s was the best option in London? The first set was a blend of Cole Porter and Blues, whilst the second was an interpretation of

Coltrane’s Crescent Suite in its entirety. I won’t write-up a minute-by-minute replay of the gig (if words could describe the music, what would

be the point of the music… yawn) but I will riff on some general highlights and points of interest and there were lots of those.

Overall it was a good gig, a very good gig in fact, but it did lack a certain ‘fire’ to my ears, a driving impetus shall we say. I suspect the second

night of his residency would have been the real roof raiser, but there was still plenty to enjoy. What struck me immediately, bearing in mind his

Wynton Marsalis disciple tag, was the modernity of his chordal style; a focus on unabashed chormaticism and ‘outside’ flirtations, all executed

with subtle fiery warmth. The way his fingers graced the keys, particularly when coaxing lush crunch chords, was an example of pure pianism.

Roberts has an entwined physical AND emotive relationship with the piano and as an audience member it’s a joy to behold.

What Is This Thing Called Love? The third number of the evening, was performed along very similar lines to this version (even the spoken

“We’d like to feature Jason Marsalis” introduction was the same.) This is obviously not a bad thing musically, but it does give away the type of

jazz musician Roberts is. Bill Evans is another pianist who practiced and rehearsed his voicings and song arrangements tirelessly, until they

best represented what he wanted to communicate. Monk, with his signature sound, also stuck to his guns. However, specifically on this issue, if

I was forced to choose one comparison it would be Evans, strange as it sounds, because both he and Roberts have a perchance for the full

pianistic range; from soft, mellow intricacies to the all encompassing rhapsodic (Gershwin in a modern jazz trio? Anyone?!)

Of course not, Roberts’ is far too consumed by the blues for such pidgeon-holing. In fact his overt Monk influences were evident in the first

blues of the night, Being Attacked By The Blues (“we all know what that is! You just have to keep fighting back!”) Midway through his solo,

brimming with quirky fills and Monk dissonance, Roberts got stuck in the high register, reeling-off lines of melodically indefinable runs. This

was an interesting technique, as it placed emphasis not on pitch or melody but on the feel of constant 8 notes, and their role in the trio’s

rhythmic cauldron. Additionally its subdued nature increased the impact of volume, especially once he’d had his fill and a smash of a midrange cluster ended the solo.

th

Throughout the 2 hour set Roberts peppered his solos with stride, elevating thematic statements and padding out the lower registers. I’ve

discussed the trio’s broad use of register a couple of times now, with intent I hasten to add as there is a great sense of orchestration within the

group. Jason Marsalis waited until the 2nd tune of the 2nd set before diving into his bag of tricks and pulling out the mallets, giving the smack

of the tom-toms a timpani feel. I find that telling.

Continuing on with Marsalis he does look like a man possessed when in the zone; glazed eyes, rigid back, head uncontrollably nodding. He

physically consumes the swing, embodies it, and is unabashed in demonstrating such passion. His groove on the open snare with brushes still

makes my foot-tap thinking about it. On reflection I don’t think he even laid the 1 beat on the kick on Where Or When, but simply smashed the

resonating ride every 12 bars whilst laying down those sick cross rhythms.

For my money bassist Rodney Jordan had the solo of the night with his compelling intro to Lonnie’s Lament. Jordan is able to educe a wailing,

masculine sigh in the deepest chasm of his instrument, quite an emotive achievement when you think most bass players rely on a higher, more

melodic range to evoke melancholy.

Ok, ok. It wasn’t a very good gig, it was a GREAT gig. As a pianist/composer the most striking lesson for me was the importance of sections, or

how effective a well structured tune can be in forcing a response from the audience. On numerous occasions the trio switched from a strict

pattern feel to a pushing, swinging free-for-all, resulting in vocal exultations from the crowd. Amongst all the complex harmony, melodic

interpretations and strict instrumental arrangements I’m reminded of, rather randomly, a Bruce Lee quote; “Simplicity is the key to brilliance.”

Marcus Roberts 5HYLHZV

Caramoor Jazz Festival: Béla Fleck and the Marcus Roberts Trio

"I want to thank Marcus for letting me live out my jazz fantasies." - Béla Fleck

The banjo might not be the first instrument that comes to mind when one thinks of jazz, but if anyone can bring

that bluegrass-bound instrument into the world of improvised music, it's Béla Fleck. Having already conquered

the worlds of classical, roots and world music, Béla - generally regarded as the world's greatest banjo player has made a career out of crossing musical boundaries, with picking that is both passionate and precise.

Béla's latest venture, Across the Imaginary Divide, was recorded last year with the Marcus Roberts Trio, one of

jazz' tightest ensembles. Marcus and Béla have been out touring ever since, landing Saturday night in Katonah,

NY where they closed out the 2012 Caramoor Jazz Festival to a packed house. Any reservations I might have

had going in about how a twangy bluegrass instrument would sound next to a traditional jazz piano trio were

immediately washed away once Béla started working his amplified banjo like Bill Frisell with five picks. As I

and everyone else at the Venetian Theater discovered, it's not much of a musical leap to go from jazz guitar to

banjo, at least in Béla's able hands.

Béla and Marcus dueled back and forth all night, with Marcus often sounding like he was playing with three

hands, just to keep up. Supporting were Rodney Jordan on bass and Jason Marsalis on drums, both of whom had

extended solos that showed they were they were Béla and Marcus' equals, at least. Béla, for his part, seemed

tickled just to be on stage with these guys: during a technical break, he told us about growing up listening to his

uncle's jazz piano albums and how wowed he was by them. He also heard Chick Corea early on as a student,

and set his mind to one day playing that music, improbable as it might have seemed then.

Towards the end of their two-hour set, Marcus quoted John Coltrane, who once said: "When I feel good energy

coming from the audience, I feel like I have a fifth member of my quartet." With a good-time vibe like this, I'm

happy to sit in any time.

(http://www.feastofmusic.com/feast_of_music/2012/08/caramoor-jazz-festival-bela-fleck-and-the-marcus-roberts-trio.html)

Marcus Roberts 5HYLHZV

Béla Fleck and the Marcus Roberts Trio: An Imaginary Divide

A banjo maestro and a jazz piano wizard showcase fresh new music, no labels necessary

By MSN Music Wed 12:45 PM

By Andrew Luthringer, MSN Music

"I'm living out a jazz fantasy up here," exclaimed Béla Fleck as he took the stage at Seattle's Jazz Alley. Fleck was

kicking off a run co-billed with the Marcus Roberts Trio, touring in support of their recent CD "Across the Imaginary

Divide." The Roberts trio is one of the pre-eminent active piano trios in jazz, but Fleck's magnanimous sentiment

notwithstanding, the goal this band has set for itself is to embody something much more than "famous bluegrass banjo

player sits in with top-shelf jazz trio." In building the repertoire together, Fleck and Roberts set out to create their own new

language, and it truly is a hybrid in the best sense of the word. The album's title also serves as the band's mission

statement, putting the group into a realm where musical labels are no longer necessary.

"We wanted to do new music, so we did do a lot of rehearsing and preparing, but the naturalness of our connection

was very welcome, and that's what was really important," Roberts told me before the set. The two first met at a jam

session and found they had an instant rapport, even though they came from different music scenes. The connection was

compelling enough to warrant more exploration. Both Fleck and Roberts have perfectionist tendencies, they like to be

prepared, and they like to push themselves into new areas, so rather than working up a predictable set of standards, they

got together and wrote a new album's worth of music.

"We really wanted this not to just be a set of gigs. We wanted a range of challenges every night. But we also need

spontaneity, so we have to have a lot of options on arrangements," explained Roberts.

To that end, the band's set featured a great deal of intricate writing and elaborate arrangements. This was not just the

frequently predictable jazz configuration of play the melody, solo, play the melody again and out. The unison lines were

frequently labyrinthine and incredibly in sync; Roberts and Fleck share a fairly telepathic rhythmic and melodic lock,

phrasing beautifully together, making the written ensemble parts a blast to listen to. Even before the soloing started, there

was a lot of burning music being played. That both artists have spent serious time contending with and studying not just

jazz but classical music was readily apparent on many of the tunes: On Fleck's "Kalimba," the ensemble tone delved into

a seamless blend of impressionistic chamber-music Americana plied with driving swing.

But virtuosic instrumental considerations aside, the band's set was also rich with welcome earthy flavors: "That

Ragtime Feeling" was drenched with a bluesy New Orleans vibe, full of humor and deep groove, compliments of drummer

Jason Marsalis. "Petunia" blended 2-feel bluegrass bass-patterned sections into flowing ride-cymbal-driven swing, and as

a piece co-written by Fleck and Roberts together, it perfectly captured the essence of what this band is about. "One Blue

Truth" was another standout, showing a slower, quiet facet of the band's sound, pushed by bassist Rodney Jordan's

masterfully melodic treatment.

Even for a player of Fleck's skill, integrating a banjo into in a jazz setting can be a challenge: The notes don't sustain

and blur the way a horn does, and the chordal component is well and fully covered by the piano. A banjo is essentially a

percussion instrument that can play notes (its roots are in Africa, and more than one observer has described it as "a drum

with strings.") There were moments when Fleck seemed to be (unusually for him) slightly outside the proceedings,

perhaps dazzled by his bandmates' explorations. But Roberts' trio has been together for many years, so it's not surprising

that Fleck needs time to hone his role and approach to this new music. On "I'm Gonna Tell You This Story One More

Time" for example, Fleck plucked and popped the notes to great effect, giving the melody more heft than it might have

from his regular finger picks.

Bing: Béla Fleck and Marcus Roberts

Though jazz can be seen as an urban music and bluegrass as a more rural form, roots in ragtime and blues are common

to both. From one point of view, jazz actually has a lot of common ground with bluegrass (particularly its nonvocal forms):

a well-defined set of tunes that everyone is expected to know, a premium put on (frequently) virtuosic improvisation and

small group interplay and plentiful impromptu jam sessions, not to mention an identity outside the musical mainstream. It's

not at all a stretch to think that fans of one form could find something in the other to latch onto.

Hence, it's easy to see why this group has been well received in open-minded bluegrass and jazz venues. Roberts

and Fleck have clearly listened and learned a lot from each other, and brought the best of their separate traditions to the

bandstand. Remarked Roberts: "We've done appearances at bluegrass festivals, and been very well received. The music

defies stylistic limitations." An "imaginary divide" indeed.

Marcus Roberts 5HYLHZV

In Conversation with Marcus Roberts

By Ted Panken

Jazz critics over the last two decades have usually ascribed to pianist Marcus Roberts the

aesthetics of “conservative neotraditionalism.” But the truth of the matter is somewhat

more complex.

A virtuoso instrumentalist and a walking history of 20th-century piano vocabulary,

Roberts is concerned with sustaining a modern dialogue with the eternal verities and

transmuting them into present-day argot. Abiding by the motto “fundamental but new,”

he takes the tropes of jazz and European traditions at face value, and grapples with them

on their own terms, without cliché.

“What I'm advocating is always to expand while using the whole history of the music all

the time,” Roberts said in 1999, articulating a theme that he more fully develops in this

interview, conducted a decade hence. At that earlier stage in his career, Roberts had

recently applied his nascent, individualistic conception of the piano trio to a suite of

original music inspired by his muse, Duke Ellington [In Honor Of Duke], and a songbook

homage to Nat Cole and Cole Porter [Cole After Midnight]. Those albums augmented a

body of work that included an improvised solo suite on Scott Joplin’s corpus, and

customized arrangements of Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” and James P. Johnson’s

“Yamacraw.”

“Ellington was not somebody who was going, ‘Oh, there's Bebop; let's throw away the

big band and solo all night on ‘Cherokee,’” said Roberts. “He was about using the logical

elements of bebop that made sense inside of his ever expanding conception. I don't

consider myself to be a New Orleans pianist, or a stride pianist, or a bebop pianist or

any of that. I study the whole history and try to develop globally that way.”

Now a working unit for 14 years, Roberts and his trio (Roland Guerin, bass; Jason

Marsalis, drums) deploy that approach on New Orleans Meets Harlem, Vol. 1 [J-Master

Records], his first release since 2001. They address repertoire by Joplin, Ellington, Jelly

Roll Morton, Fats Waller, and Thelonious Monk, laying down a pan-American array of

grooves, channeling the essence of the old masters without regurgitating a single one of

their licks.

“Marcus Roberts was a whole other whole category of musician for me to play with,”

Wynton Marsalis told me a few years later, reflecting on the ways in which Roberts, who

in 1986 replaced the mercurial Kenny Kirkland in Marsalis’ band helped trigger a sea

change in the way Marsalis viewed his own musical production. “I had never encountered

a musician around my age with that level of intelligence and depth of feeling about the

music. He gave me a lot of strength. He made me understand you can’t make it by

yourself. You have to play with people, and his music is about getting together with other

people. Marcus made me understand that if a person has a belief, that is their artistry.

What Marcus Roberts told me then (and we were both very young men) is the truth: Your

artistry is your integrity and who you are as a man. Who you are as a person. What you

are about. What’s inside of you. That’s the most important component not whether you

can hear chords quicker than somebody or play a more complex polyrhythm. I learned

that from him, and from watching him and his development.”

Is New Orleans Meets Harlem, Vol. 1 a recording that you’ve been trying to find the

right time to release over the last few years, or is it very recently recorded?

Well, I’ll tell you what. I first recorded it in 2004. I edited it and mixed it and mastered it,

and ultimately it just wasn’t quite what I wanted it to be, so I re-recorded it in 2006, and

now I’m putting it out. It’s really the second version. I redid the whole thing. If I’m going

to put it out, in my estimation, I need to be happy with it if I’m going to expect anybody

else to be happy buying it.

What dissatisfied you about the first incarnation?

I can’t even put my finger on it. I just didn’t feel that it captured where we had evolved

to. By the time I’d fixed it and edited it and did all the post-production, we were playing

honestly so differently that it didn’t feel to me as though we had captured that in the first

iteration. The other issue was that the last recording of mine on a major record label, Cole

After Midnight, came out in 2001, but it was actually recorded in 1998. In other words,

the last anybody heard of my work really dates back 11 years.

What are some of the reasons for that gap? It’s not like you disappeared and hid in

a cave. You’ve been performing a lot.

It’s been a few things. For one, after leaving Columbia I knew that I didn’t want to sign

with another major record label. So I was no longer interested in going in that direction,

but at the same time, a lot of possibilities now available on the internet had not matured

yet. A lot of changes were still in process, and I wanted to wait and allow us to use these

different methods, strategies, and approaches to disseminate our work to the public.

The other reason was that, as happy as I was with my group, we needed to do some work

to fill in some conceptual holes that I thought were there, and I didn’t want to record

anything until I felt those things had been resolved.

The third reason is pianistic. I needed to look at some major things to overhaul my

technique, which you really have to do every five or ten years. You need to constantly

examine what you’re doing, what you think about your general approach to sound, what

new technical principles you’re interested in exploring that might require real time. So I

felt I needed to take some time and invest myself in the piano to prepare for the next big

stage of my career.

Those were the main reasons, off the top of my head, why it’s been so long. One final

one is that I took a job, a halftime position at Florida State University, my old school, to

teach jazz and help them with my jazz program. I’ve been teaching young people my

whole life, since I was a kid. I always liked doing it. You learn a lot when you teach,

because you really have to think about what they need, what their talents and gifts are,

and find a way to develop them using their skills and abilities, not just your perspective.

It’s hard work if you want to be good at it, and it took a long time. I’m in my fifth year at

FSU, and finally I feel I’m making a real contribution to the program.

Let me follow up on points two and three. You said the trio needed to bolster some

things conceptually and you needed to overhaul your technique. What specific

technical and conceptual things were you looking to do?

I was developing a real interest in exploring more deeply how classical music and jazz

could be presented together. That meant I needed to invest more time. Conceptually, I

was and am interested in exploring a much more refined approach to sound, which meant

that I needed to pick up some old repertoire and really investigate it. Bach, for example,

which is the foundation of any keyboard technique. I wanted to go back to Bach for my

concept of contrapuntal playing, viewing the piano as an instrument that is primarily

interested in more than one line at a time, which is one of the big gifts that the piano

offers. Another issue is to be able to play these lines with a certain amount of balance and

clarity and articulation-so Bach is perfect.

Another issue has to do with balance, being able to work on voicing and pedaling so that

you can increase or expand the amount of nuance that you are capable of playing on the

piano at any given time. I tried to focus on making sure that, if I’m playing something

soft . . .well, where is the threshold when I feel I’m starting to gain control of that nuance,

of these soft colors?

You can play a lot of different things when you study classical piano. The literature is

clearly laid out, so if you know which things to study, you can cover a lot of territory. For

example, if you’ve been trying to work on articulation and more of a light, clear touch on

the instrument, you’ll play Mozart for that. If you want to deal with color and sonority,

well, you can’t get any better than Debussy and Ravel. If you want somebody who is in a

direct line from Bach and Mozart, but a more romantic, sensual attitude, then Chopin is

challenging, because you have to be able to play things very light and beautiful, but also

play certain passages with tremendous power and virtuosity.

It’s hard to do consequential research and development when you’re on the road a

lot, too, isn’t it?

Well, it is a difficult thing to do when you’re on the road. It’s difficult to do when you’re

in the middle of presenting music that you’ve been playing for a while. New information

reinvigorates you. Inspiration, in my opinion, is the key to a good imagination. Without

inspiration, you just start playing the same old stuff, and your playing becomes, in my

opinion, annoying and predictable-and I just don’t ever want to go there. I’ll stop first.

There is no point putting on the stage something that you don’t care enough about to

work on. That’s just for me. Whether we want to call it 'new' or 'old' or 'innovative' or

whatever else, if you’re not investing in it every day of your life, then you’re not as

serious about art as some great artists have been. That’s all I can say.

Back to point two, what did the trio need to accomplish?

I have to say that they’re so talented. Jason Marsalis is capable ... You might sit down

with him and be playing just a regular B-flat blues, and say, 'You know what? We’re

going to modulate to A-minor, and when we modulate to A-minor I want you to keep the

same form but play it in 7/4 time.' He has perfect pitch, so when you modulate he knows

you’re there, plus he can keep track of those two time signatures at the same time. No

hesitation. Roland has a different kind of natural ability to use syncopation and grooves

on the bass in this more folk type of style-funk music, zydeco, Louisiana playing-and also

has a love of Ron Carter’s role in the Miles Davis Quintet, and a real deep connection

with Jimmy Garrison from Coltrane’s group. He’s figured out a way to put all of that

stuff together. The two of them playing together get this sophisticated, more abstract

view of groove and time and rhythm.

What I wanted to achieve with them was showcase that talent—write arrangements that

would make it easier for them to exploit nuance. That’s one component that the public

can address and digest comfortably. In the same way that when you go to a very

sophisticated restaurant, you may not know the 20 ingredients in this chicken dish, but

you know that it tastes good, and you know that there are some subtle reasons why. So I

wanted to pay attention to these nuances and go in the direction of some of the other great

trios that existed. The Oscar Peterson Trio was fantastic. Their execution was flawless.

They had such a huge dynamic range. When Ray Brown would start to take a bass solo, it

was a bass reflection of OP’s virtuosic piano sound and style. Or Ahmad Jamal, who

right now, today, can sit down at a piano and blow you away by himself, with a trio, with

his conception, with his accompaniment ...

Frankly, we live in a loud culture, so everybody’s view of a jazz trio is kind of, 'Oh yeah,

cocktail music,' or 'it’s kind of cute, it’s kind of nice ....' Now, if we want the American

people, or any other group, to take a jazz trio seriously, we have to work hard to present a

group that has the same power, virtuosity, and delicacy that we can find in a quartet, or

quintet, or septet.

The second way to do it is by flipping around the roles of the piano and bass and drums.

My modern view is that if we make room for the bass and the drum, they’ll be able to

have equal access in bringing us where we’re getting ready to go. If Roland wants to

change the form or the tempo, how do we set up a cue system so we actually can do that

without the piano having to set it up? We had to figure out how to do it, and that changed

the way we play.

You’ve been evolving that concept for some time, haven’t you? You were talking

about this ten years ago.

We talked about it ten years ago as a conception. It became a philosophy when we really

started to be able to do it. That’s the difference. The conception is always something that

we can talk about, but the question is whether you’re going to really push and figure it

out, or whether it’s going to be mainly conception.

Looking at the repertoire and the concept of the recording, I can’t help but be

reminded of the recording Alone with Three Giants, from twenty years ago, on which

you interpreted repertoire by three of the composers—Morton, Ellington, and

Monk—whom you represent on New Orleans Meets Harlem. Let’s talk about the arc

of the repertoire. It seems to represent a fairly chronological timeline from the turn

of the century to modernity, beginning with Jelly Roll Morton and Scott Joplin, and

concluding with tunes by Monk and your own original piece.

When you’re putting any record together, you’re trying to sequence it in a way that shows

contrast and the naturalness of the set, so that when people listen they don’t get tired in

the process. I’ve even listened back to some of my own records and thought it was a little

too intense the whole time. Just general observations.

So you want an ebb-and-flow?

Yes. You want people to have time to digest what they’re hearing. So we start the thing

with Jelly Roll; he’s at the beginning anyway, so why not? 'New Orleans Blues' I thought

was a good selection to start it off. Also, we kind of used that blues by Jelly Roll to be a

sort of microcosm of jazz, because the way we do it, we are able naturally to cover a

broad range. From my vantage point, the 21st century in jazz music has to be about

presenting or being informed by the entire history of jazz at all times, not restricting

oneself to a particular ten-year period. Which may have been how the music was built,

brick-by-brick. But at this time in history, we live in a collaborative community, a world

community, a global community. Where technology is right now, everything moves at

the speed of light, and jazz music is the one music that can keep up with it. It has

everything in it. It has virtuosity. It has folk music. It has stuff from the inner city. It has

grandeur and sophistication and aristocracy in it. It has democracy in it. It has perhaps

even tyranny in it, depending on who the bandleader is. Everything is there.

Most of the pieces on this CD I’ve been playing for years. There’s not really a whole lot

of new material. What is new about it is that it’s all trio, and the concepts are organic,

because I’ve been playing this stuff for a long time, and I've figured out how to rebuild

from the ground-up to where it has a specific individual sound. To me, that was an

important component.

So your Duke Ellington homage, In Honor of Duke, which was primarily comprised

of original compositions, or Cole After Midnight, or Gershwin for Lovers, all trio

recordings from the ‘90s ... how do you see those now?

I don’t really see them in any particular way. A record just reflects where you are in your

development. For example, Gershwin For Lovers was with Wynton’s rhythm section, not

my band. That was about slick arrangements, to give a good record to Columbia that I

thought they could sell. In Honor of Duke represents the beginning of my original trio

conception. When you come up with a concept that you believe is different or new, you

often have to use original music to bring it to the forefront, because there’s no music

written for the conception yet. So I wrote that music, and also the previous record, Time

and Circumstance, to represent the concept, if you will. But New Orleans Meets Harlem

represents the philosophy. It’s matured. It’s grown-up. It’s no longer really a concept. At

this point it’s more a way of life. It’s how we play, what we believe in.

At what point in your life did the notion of having the entire timeline of jazz

interface in real time become part of the way you thought? I’m sure it took a while

to germinate, and once it began to germinate, it took you a while to find your way

towards articulating it. Were you thinking this way before you met Wynton

Marsalis?

I guess it’s always been there. Meeting Wynton was more confirmation than introduction.

But the thing about Wynton is, he’s the only one in my generation who could articulate

intellectually and with any real clarity what we were doing and why we were doing it,

and he was the only one who really knew how to execute and operationalize it. Again, a

lot of people have great ideas, but they don’t know how to make them operational. You’ll

get in the middle of it, then: 'Oh, I didn’t consider it whole.' 'What do we do now?' 'I

don’t know.' So making ideas operational is important, and as I have developed, I have

had to work very hard at sniffing out how to streamline some of my concepts, to bring

together an operational structure with a conceptual structure.

Those are the real problems artists like to solve. For example, when you write a piano

concerto, it needs to be playable. I mean, it might be difficult, but it shouldn’t have you

doing something that’s physically going to hurt you. So if you play a great piano

concerto, or a great piece by Chopin, what’s amazing is how well it lies within the natural

reach of the hand. He’s got all these problems with thirds and octaves and chromaticism

and these kinds of elements, but he also has the solution right there. You just have to

practice it!

As far as when I started to think in terms of the history… Well, I’ve always been in

search of one general sound that I heard in church when I was 8 or 9 or 10 years old. I

can’t even explain what that sound is. From time to time, you hear and play things that

have an eternal resonance. You’ll play or hear a melody, and you don’t know when it

could have been written. It could have been ten thousand years ago. Somebody might

have hummed that way in Africa someplace, or in Japan, or in Europe. It’s timeless. It’s

beyond the scope of our understanding. It’s like a subconscious/unconscious thing. Then,

there’s the conscious implementation of a design that you impose on it that’s more

'modern,' new, relevant for our time, relevant for our generation, etcetera. But to me, you

need both. I’ve always thought in terms of integration of more than one thing. That takes

you into the realm of multiplication as opposed to addition. I mean, it becomes easy to

play something 'new.' I’ve never had any shortage of creativity or imagination. I’m sure if

you talked to Wynton for any length of time, he could say the same thing. It’s never been

a problem actually to find new things to do.

One thing you do that Wynton likes to discuss when he talks about you, which he

says is new and is pretty distinct unto you, is your ability to play different time

signatures with two hands.

That came as a result of playing with Jeff Watts. It’s a different view of rhythmic

syncopation. Monk was a master of syncopation; his music has syncopation built in on

multi-levels. There’s the syncopation that occurs between any two notes that are a halfstep apart. That’s my real view of blues—the tension that is established harmonically

between two chords that are a half-step apart, two notes that can be a half-step apart,

between a rhythm that could occur on-beat and another rhythm that could occur on the

end of one. Syncopation means we’re imposing something on it against the ear. The ear’s

got into this, and then we’re going to change it this little bit. It could even be dynamic

syncopation—your ear has gotten accustomed to something soft, and all of a sudden,

BAM, here’s something loud. It could be the syncopation of two instruments playing, and

now, all of a sudden, we’ve got a third instrument. It’s a real complicated thing.

When you get to rhythm, once you have the general understanding of where the quarter

note pulse is, and a tempo that is carrying that pulse, then the only issue is to determine

on how many levels can we interject this quarter note pulse. Tain was able to calculate

and understand the real math behind these permutations. To be honest, I never really

understood it the way he and Jason Marsalis do. They’re on a whole different planet as

far as understanding the rhythms you can play at these various tempos against other

things. So that was a big part of Wynton’s philosophy, and my philosophy with my

group. I was interested in adding blues to that concept, so that always, whatever the

tempo or concept, it has the real feeling of jazz. That’s that folk element I’m talking

about.

Like, when you hear Mahalia Jackson sing. That voice—she could have been singing it a

thousand years ago. It goes way beyond the generation you’re in. As I said earlier, you

want to get beyond reducing anything to a ten-year period, which is kind of what a

'generation' is. When you hear a Bach chorale, are you really thinking about 1720? No!

You’re thinking that it’s moving you right now. ‘Wow, this is beautiful. How did

somebody write that?’ If somebody could write a Bach chorale right now, trust me,

nobody would be mad! They’d say, ‘Oh, Well, my-my. Somebody can do that again?’ So

we’ve got to be real careful in terms of how we evaluate critically the value of something

based on the time period that it took place in. That’s a delicate issue.

New Orleans Meets Harlem, Vol.1 begins in 1905, with ‘New Orleans Blues,’ and

ends in 1956 with ‘Ba-lue Bolivar Blues Are.’ So you’re spanning the first half of the

twentieth century in American music—In Black American music. Do you have any

remarks on the broader implications of this body of work?

Again, they solved problems. ‘Ba-lue Bolivar Blues,’ or any great blues that Monk wrote,

has layers of syncopation that we can look at. Monk’s music to me always sounds like

poetry or real modern folk music. He’s almost a modern equivalent of Jelly Roll Morton.

Monk’s music is strictly jazz. Strictly. You’re not going to confuse it with German music,

you’re not going to confuse it with African music, you’re not going to confuse it with

anything. American jazz. Period. If somebody said, ‘Give us four pieces of music that

sound 100 percent like jazz,’ well, you’d pick a Jelly Roll Morton piece or a Louis

Armstrong piece, you’d probably pick a Monk piece, you might pick something from

Kind of Blue. I won’t speculate on the final thing. But for sure, you couldn’t go wrong

picking a Monk piece. You couldn’t go wrong picking a Jelly Roll piece or a Louis

Armstrong piece. You probably couldn’t go wrong picking a Duke Ellington piece. Why?

Because that music has such expansiveness.

Monk, Jelly Roll, Fats Waller, Joplin, and Ellington: all were serious about the piano and

serious about exploring different forms, different types of nuance, which is what I’m

interested in. For me, it’s always a question of figuring out who has the information that I

need to develop my artistry. That’s the selfish component. Now, I’m not necessarily

going back to Jelly Roll Morton to be caught up in recreating what he did. First of all, it

would be very arrogant to pretend you could do that anyway. Because you’re talking

about somebody’s life’s work, what they really went through. And again, these

recordings are just a snapshot of part of a day of your life.

And Jelly Roll Morton had quite a life.

Man, quite a life. So I think the more relevant issue is what part of Jelly Roll Morton is

also part of me and what I believe. So I’m playing ‘New Orleans Blues,’ which is a staple

piece that I always will play and always have played. ‘Ba-Lue Bolivar Blues,’ I don’t

know how many arrangements of that tune we haven’t thought up in this trio. We’ve

played it all kind of different ways. ‘Honeysuckle Rose’ is another one that we’ve played

several different ways. The version on this record is not exactly the same version from

2004.

I think the importance of all the great composer-pianists, first of all, is that they reflect a

range of understanding of the piano. Scott Joplin wrote down his music. He knew what

he wanted people to play. Of course, he didn’t really want folks improvising on it, but we

do it anyway. But he was a serious scholar of the piano. His music, again, has this urban

sound, but also this melancholy—a kind of aristocratic Folk sound. It also has this

connection between pre-jazz and the classical music of Chopin. In other words, it has

variety built into it. It has options built into it. It’s an operating system, like Windows XP.

You can put anything that you conceptualize inside of that. It doesn’t impose the moves

of what it can be, but it does say, ‘Well, you’d better write it in 32-bit code, or the

operating system won’t acknowledge it.’ There’s the science of it, and there’s the art of it,

the creative element. Again, you’re always balancing the design with the conception.

Who are some of your contemporary piano influences? By ‘contemporary,’ I mean

roughly within your generation. Ten years ago, you mentioned to me Danilo Perez,

and I’ve heard people who know you mention Kenny Kirkland, whose chair you

filled in Wynton’s group. Are there other people within striking distance of your

birthday who have influenced you?

Those probably would be the two. Kenny Kirkland, first of all, just his knowledge of

rhythm, his knowledge of harmony, and how he could intersect the two using not just

Latin influences, but also chordal structures taken from the music of Bartok and

Hindemith. He was a modern thinker. A lot of stuff Kenny was playing was way more

profound than the structure that he played in. He understood theory on an extremely high

level. He’d play a chord that had a rhythmic function to hook up with Jeff Watts and a

harmonic function to hook up with Wynton or Branford, whoever was soloing at the time.

He also, frankly, was typically the most serious person on the stage. Kenny Kirkland was

one of the most consistent pianists that you could hear. I mean, tune after tune after tune,

he was swinging, playing an unbelievable modern vocabulary, a great sense of Herbie

Hancock’s and Chick Corea’s conception, but again, put in this really modern but

delightfully percussive manner—because it still has the theory and this European training

behind it.

Danilo is someone who understood another culture’s view of our music, and was able

again to interface them very organically. He could sit down with you and explain how he

did it. Again, it’s that concept of making something operational. Any programmer, before

they start writing code for a computer program, first has to understand the function of the

process. Once we know the manual procedure, then we can automate it. Danilo

understood manually each of these styles, then he figured out where they intersected, and

then he picked music to showcase what he’d figured out. It’s just brilliant stuff. It’s wellexecuted pianistically. I personally hate sloppy piano playing—somebody who doesn’t

understand that the sustain pedal is there and what you’re supposed to do with it. He’s a

refined player. He understands the vocabulary of these Latin cultures, where he can get

away with superimposing it, where he should leave it alone. Also, he inspires the

musicians he plays with, which is another job of a pianist. You have to provide an

inspirational environment for the bass player and the drummer to do their thing. You

have to know when to lay low and stroll so that the piano doesn’t get in the way of what

somebody else is trying to play, even if it’s your conception, your philosophy and your

group viewpoint. It’s a hard job. It’s not for the faint-hearted.

You were mentioning earlier that you’ve been looking your whole life for a sound

that you heard as a kid in church. One development in jazz since you and Wynton

got together has been a burgeoning of black musicians with church backgrounds

and southern roots. This coincides with a period when MTV and hiphop were rising

in visibility and influence, and jazz wasn’t part of the zeitgeist. Any speculations?

Well, I can’t speak for anybody else’s experience. I can only tell you that this was the

source of my upbringing and what led me into the piano, led me into jazz music, and that

sound spoke to me. Now, did it speak to me differently than it spoke to Charles Mingus

from Los Angeles, California? Probably not. I don’t know.

I'm thinking of the time and place in which you grew up.

That’s still so personal. The only thing I can tell you is, somehow or other, you’ve got to

access two conflicting things. One is the value of something that is bigger than you, older

than you, greater than you; the other is the physical organization that is from your

generation. That’s the issue. If you grew up in church, then you found access to it that

way. If your parents were jazz musicians, like Jason and Wynton and Branford ... Look,

they didn’t play in church. Obviously, the church is not the only way to find it. I think the

main key for any jazz artist, any serious artist of any style, is you must find a connection

with the beginning of it somehow. Somehow. It is never going to be enough for it to

come just from your generation. That’s never enough. You’re not going to find anything

great without it.

With your own label, do you plan to document your work more frequently?

Well, I’ve been documenting a lot. That hasn’t been the problem. There are a whole

bunch of records still to come out. Oh yes! But I’m just starting to put the stuff out. We

certainly won’t be waiting another eight years to put out a record. It will be more like six

months.

Primarily trio, or diverse contexts?

It’s diverse. I have a solo piano record that’s already done. I have another trio record of

original music that’s done. I’ve got some septet stuff from live shows that I plan to put

out—I don’t know if I’m going to go in and redo it. But yes, I’m always trying to deal

with a diversified viewpoint.

Any special projects for the spring and summer?

The most important concerts that I have coming up are with the Atlanta Symphony.

[These occurred on April 4th-6th.] We’re doing Gershwin’s Concerto in F for Piano and

Orchestra. That’s important to me, because that’s the first major symphony orchestra in

the United States that we’ve done this work with. I hit it off with Robert Spano; he’s a

great conductor over there. So I’m hoping that we can do a lot more work with them. I’m

talking to him about possibly trying to do the same sort of thing with the Ravel Left Hand

Concerto that I did with the Concerto in F. For me, that would be a huge undertaking,

and it would take a tremendous amount of time and effort to pull off. But we are

discussing it. At this stage of my career, I’m interested in meaningful collaboration. It’s

certainly a little more streamlined. I’m not interested necessarily in just the regular playgigs type of career.

Ted Panken interviewed Marcus Roberts on March 24, 2009.