Grey Markets

advertisement

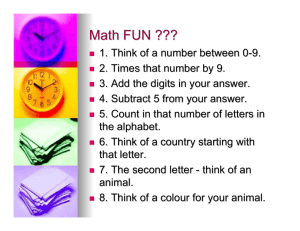

PART D go online Go online to <www.pearsoned.com.au/fletcher> to find more case studies. CASE STUDY 17 Grey markets Chloe Savage and Richard Fletcher I N T E R N AT I O N A L M A R K E T I N G I M P L E M E N TAT I O N 710 During the normal course of business, manufacturers of goods are able to deliver them to consumers through predefined and negotiated distribution channels. These usually involve contracts and agreements which set out the rules of distribution, such as point of sale, recommended retail price and warranty issues. Outside these distribution channels there operate grey markets. A ‘grey market’ refers to the flow of goods through distribution channels other than those authorised by the manufacturer and often involves the goods being bought and sold at prices lower than those that prevail in the local market. Grey markets affect a broad range of products including, but not limited to, recording companies, publishing houses, makers of computer software and computer games, food and beverage companies, automobiles, pharmaceuticals and fashion accessories. To the manufacturers of products so affected, grey markets pose a significant concern. The main advantage of grey markets to consumers is the significant savings they receive from the products they purchase. KPMG LLP in the USA conducted research into the effects of grey markets on the IT industry. It showed that average savings when buying products from grey markets instead of from authorised distribution channels can be significant. Fifty-seven percent of respondents cited savings of between 10% and 30%, as illustrated in Figure 1. However, this price advantage often comes with many drawbacks that various manufacturers try to highlight when defending orthodox distribution channels. Products available through grey market sources are often sourced from oversupply in another distribution channel. They are sold off at significantly lower prices to get rid of excess stock and are then sold to the consumers at lower prices, often in different countries, without the knowledge of the producer. In the past, parallel imports for certain goods were considered unlawful as they infringed on copyright and trade marks, and were in common law viewed as passing off and misleading or deceptive conduct. Intellectual property rights’ owners and their licensees often blocked such imports. In the past 15 years however, the government of Australia has passed legislation which restricted the rights of the intellectual property (IP) owners and made parallel importation a lawful conduct (Barraclough 2006). Provisions in both the Copyright Act 1968 and the Trade Marks Act 1995 relating to parallel imports adopt the principle of international exhaustion. This theory provides that once a trade mark or copyright owner places goods onto the market, the owner’s ability to control subsequent dealings with the goods or services is exhausted (Barraclough 2006). Under section 123 of the Trade Marks Act, a person may import goods which bear the trade mark of another party as long as the trade mark was applied to those goods with the Australian registered trade mark owner’s consent, even if this has occurred outside Australia. This provision 40 Percentage of respondents 35 30 25 20 36% 15 22% 10 21% 14% 5 7% 0 1–10% 10–20% 20–30% Range of price advantage 30% and above SOURCE: KPMG LLP (2000) The Grey Market, <www.kpmg.ca>. has been part of the Trade Marks Act since it came into force in 1995 (Barraclough 2006). Some retailers that resell products on the grey market are not able to provide the same quality of customer support as would be the case if they had dealt with authorised distributors. The grey market products usually have limited or no warranty as in most cases the warranty is only valid in countries in which the product was purchased through the authorised distributor and the manufacturer will not honour warrantees on grey market purchased goods. In these situations the customer often has to pay the manufacturer to perform repairs that would have been provided free of charge had the purchase been through authorised distribution channels. Generally grey markets are not illegal, but some illegal products can be masked as parallel imports, causing consumers to purchase counterfeit goods. Another risk of grey markets is that consumers may be buying obsolete products. Warehouses clear stock at below market prices in anticipation of a new product which is more technologically advanced and often cheaper. The consumers then fall into the trap of buying what they believe is a new product at a very discounted price only to realise a short time later that they 711 EFFECTIVE DISTRIBUTION OVERSEAS 0% could have purchased a far better product at a lower price. When designing and distributing products to different markets, producers of consumables especially make the product based on the tastes and requirements of the market of the intended point of sale. Consumers are usually not aware that they purchased the product on the grey market and subsequently after experiencing the problems outlined become disgruntled with the producer of the product. On occasion grey markets can be encouraged by a retailer looking for a larger margin on a product and the retailer seeks out a different distributor, often in another country. This is sometimes referred to as parallel importing. Parallel importing can be defined as goods that are imported through ‘non-official’ channels from low-price to high-price countries (Find Law Australia for Students 2006). This case study will examine the grey market dispute between Nestlé and the new supermarket chain in Australia—Aldi. In late 2005 Aldi became involved in a dispute with its supplier Nestlé over what Nestlé claimed was the deliberate attempt by Aldi to circumvent Nestlé’s established distribution channels in Australia. Aldi sourced its Nescafé Blend 43 coffee from its Indonesian distributor. Aldi claimed that Nestlé prevented Aldi from access to the same buying conditions it extended to the Woolworths and Coles chains in Australia and to compete with them it would have to sell the product at a loss. Frustrated, Aldi initially turned to a Singaporean distributor and later to a Brazilian distributor in its efforts to bypass Nestlé Australia (Baker McKenzie 2006). One of the risks entailed in such action is that since the product has been acquired from a different country, it may not be compatible with the standards that apply in the country of final sale— as with electrical products that are not compatible with Australian power outlets. In Australia, this can be a breach of sections 52 and 53 of the Trade Practices Act 1974). Nestlé claimed that it received large amounts of negative formal and informal feedback and complaints due to customers purchasing Nescafé CHAPTER 17 FIGURE 1 Savings to consumers from grey markets PART D I N T E R N AT I O N A L M A R K E T I N G I M P L E M E N TAT I O N 712 Blend 43 that was manufactured to a weaker strength to conform to Indonesian tastes. Aldi responded by putting stickers on both the product and the surrounding shelf areas to inform its consumers of the origin of the product. Nestlé argued that this action was inadequate and refused to supply Aldi with any more products, including other coffee products and the energy drink Milo, until ‘Aldi improved in-store information about the parallel imported coffee’. Nestlé also proceeded to file a claim with the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) in December 2005, outlining the reasons for its actions. On 9 August 2006 the ACCC revoked Nestlé’s notice and therefore its immunity from prosecution for exclusive dealings (i.e. barred further supply of Nestlé products to Aldi) under the Trade Practices Act. The ACCC chairman, Graeme Samuel, stated that: Aldi had taken adequate steps to ensure consumers were making informed choice. The ACCC response further elaborated that Nestlé’s reasoning behind the notice and its discontinuance of the supply of its products to Aldi: Questions market policies’, Managing Intellectual Property, <www.proquest.umi.com>, accessed 22 October 2006. Coffee Scout (2006) The Australian Coffee War, <www. coffeescout.net>, accessed 20 October 2006. Dibb, S., Simkin, L., Pride, W. and Ferrell, O.C. (2006) ‘Modifying the marketing mix for various markets’, in Marketing, 4th edn, Houghton-Mifflin, Warwick, UK. Find Law Australia for Students (2006) Nestlé vs Aldi, <www.findlaw.com.au>, accessed 22 October 2006. Gittins, R. (2006) ‘Why what we don’t know can hurt us’, Sydney Morning Herald, <www.smh.com.au>, accessed 23 October 2006. Kayasit, P. (2006) ‘Asia’s rules on grey market goods’, Managing Intellectual Property, <www.proquest. umi.com>, accessed 22 October 2006. KPMG (2006) The Grey Market, <www.kpmg.ca>, accessed 28 September 2006. Venu, S. (2004) ‘Should parallel imports be regulated at all?’, The Hindu Business Line, <www.thehindu businessline.com>, accessed 23 October 2006. 1 What are the effects of grey markets on producers and manufacturers? Explain in relation to: a profits; and b brand/company image. 2 Name some specific products and companies which relate to the grey market and parallel imports issues. 3 Outline ways in which companies may protect their products against appearing in grey markets. 4 Draw a product distribution network map representing this case study. It must show the distribution channels from Nestlé to the final consumer, depicting the normal distribution channels alongside Aldi’s grey market distribution channel. Bibliography Baker McKenzie (2006) Nestlé Australia Ltd—Exclusive Dealing Notification N31488, <www.accc.gov.au>, accessed 23 October 2006. Barraclough, E. (2006) ‘Companies rapped over grey • substantially lessened competition in the instant coffee market; • discouraged and eliminated a new source of competition for the local (Australian) Nescafé instant coffee brands; and • removed the stimulus to other Australian grocery retailers, who might have responded to Aldi’s sale of the imported Nescafé instant coffee by discounting Nescafé Blend 43 or importing similar products. The ACCC’s judgement showed that it viewed the refusal to supply Aldi as going much further than was needed to inform consumers.