- British Humanist Association

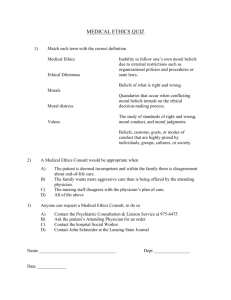

advertisement