Flexible Delivery in Higher Education

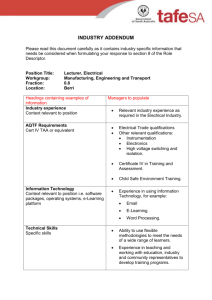

advertisement