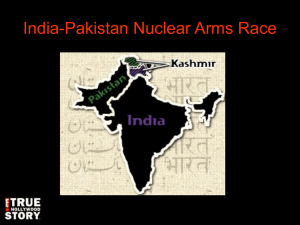

Nuclear Stability and Escalation Control in South

advertisement