Competition Law and Policy in Philippines

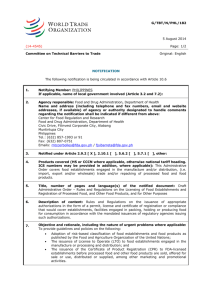

advertisement