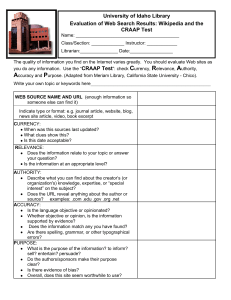

Field of Dreams Fallacy

advertisement