Interpretative Guidelines on Electronic Commerce

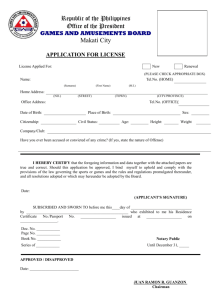

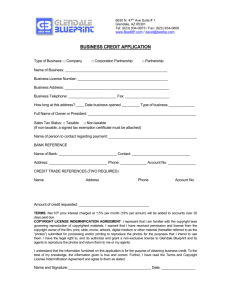

advertisement