Knowledge Profiling: The Basis for Knowledge Organization

Knowledge Profiling: The Basis for

Knowledge Organization

Torkild Thellefsen

Abstract

How are we able to construct truly realistic representations of knowledge organizations (KOs)? The paper introduces and defines the knowledge profile as a method to investigate the epistemological basis of any KO to outline the consequences this basis has upon its research object.

The knowledge profile is inspired by C. S. Peirce’s doctrine of pragmaticism, and it further reflects the relevance of pragmaticism in the context of KO.

Introduction

When trying to make a representation of a given knowledge organization (KO) 1 the best place to start is to investigate the epistemological basis of the knowledge domain—this foundation is the fundamental sign of the knowledge domain (Thellefsen, 2002, 2004). The basic premise is, “When trying to identify a KO and afterward trying to represent it, the least we can ask for is that the representation truly represents the KO in the knowledge domain and in respect of its knowledge structures. If this is impossible due to the character of the knowledge domain, then the least we can ask for is that the representation truly represents distinctive features of the knowledge domain, and by distinctive features I mean the essence of the knowledge domain.” Therefore, I do not think that either the structure of the classical thesaurus as we know it from library and information science (LIS) or the way LIS identifies knowledge 2 is capable of representing the true KO of a knowledge domain. On the contrary, the thesaurus structure is a nonrealistic structure that is forced upon the domain, often by librarians or information specialists. Instead, I suggest a drawing of a knowledge profile

Torkild Thellefsen, Aalborg, Department of Communication, Kroghstraede 3, 9220 Aalborg

Sø, Denmark

LIBRARY TRENDS, Vol. 52, No. 3, Winter 2004, pp. 507–514

© 2004 The Board of Trustees, University of Illinois

508

library trends/winter 2004

of the knowledge domain. Indeed, this article aims to define the knowledge profile and to clarify how to draw a knowledge profile. In my opinion, that is a far better way of identifying the KO of a knowledge domain than the rigid and nonrealistic thesaurus structure. Moreover, as shown in Thellefsen (2003), the knowledge profile also can be used to sharpen the terminology of a certain research project; it is a method that helps to keep a research project on its terminological tracks. It is a method that I impose on my students to keep their project in accordance with their chosen epistemological basis. If someone chooses to study a problem from a hermeneutic angle, it has other consequences for the research problem than using a phenomenological theory or a pragmatical one for that matter; these consequences have to be identified and dealt with or else we end up in a situation that the American philosopher C. S. Peirce refers to as “terminological unethical behavior.”

By drawing a knowledge profile, we are able to identify the epistemological basis of a knowledge domain, and we are capable of identifying the consequences of this epistemological basis. The consequences reside in the way the knowledge domain correlates its research objects and in the ways in which it develops concepts and theories. In the following, we shall take a closer look at how to draw a knowledge profile and where we can use it.

Basically, the knowledge profile is about sharpening terminology. It is about removing redundant and misleading connotations in order to make the single concept or related term appear as sharp and precise as possible.

Indeed, it is necessary to sharpen terminology to create a scientific terminology that is able to communicate knowledge in a precise way. There are several ways of using the knowledge profile; here, I will develop a knowledge profile for the concept “fundamental sign,” which is a concept I have defined in relation to the semiotic KO method called SKO (Thellefsen,

2002, 2004). The knowledge profile also can be used to identify the epistemological basis of knowledge domains, both small domains involving few researchers and vaster domains both scientific and nonscientific. The essence of the knowledge profile is that every choice made results in consequences and these consequences are identifiable. Theoretically, this is anchored in Peirce’s doctrine of pragmaticism, which, in short, is defined as follows: “Pragmaticism consists in holding that the purport of any concept is its conceived bearing upon our conduct” (CP 5.442). And further: “ . . .

pragmatism does not undertake to say in what the meanings of all signs consist, but merely to lay down a method of determining the meanings of intellectual concepts, that is, of those upon which reasonings may turn” (CP

5.8). Furthermore, Peirce writes: “Now pragmaticism is simply the doctrine that the inductive method is the only essential to the ascertainment of the intellectual purport of any symbol” (CP 8.209). Hence, it is the consequences of intellectual action that grant us insight in meaning or in a more biblical way: it is “by their fruits ye shall know them” (Matt. 7:15–20).

thellefsen/knowledge profiling

509

Knowledge Profile for the Fundamental Sign

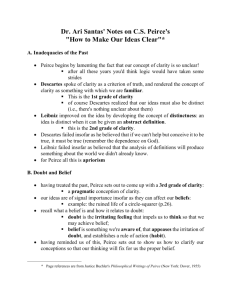

Figure 1 is a diagrammatic knowledge profile of the fundamental sign.

When creating a knowledge profile of a concept, project or a knowledge domain, the first thing to do is to consider the most general level that has an influence on the concept. In the case of the fundamental sign this general level is the concept “semiotics.” This concept is so general and vague because it contains all kinds of theories that deal with signs. It contains both the European structural semiotics and the American pragmatic semiotics, and this almost makes the concept useless. By prefixing “pragmatic” to

“semiotics” we get a much more precise concept. “Pragmatic semiotics” refers to Peirce, and this rules out the pragmatic theories of Dewey and James, for example. However, we can sharpen the knowledge profile even further by defining the fundamental sign in relation to Peirce’s doctrine of pragmaticism. At this time, we have defined the fundamental sign in relation to Peirce’s pragmaticism. We could say that we have prefixed the fundamental sign with pragmaticism. This means that it is within the doctrine of pragmaticism that we understand the fundamental sign. Now we are getting closer to the knowledge profile of the fundamental sign. However, we are able to sharpen the definition a bit more. Using pragmaticism involves understanding knowledge and thus concepts such as fallibilism, idealism, realism, and within Peirce’s phaneroscopy. In short (referring to Thellefsen, 2004 for a thorough discussion of these concepts), fallibilism means that knowledge is provisional. Knowledge contains a potential of development. In this pragmaticistic context, idealistic means that the concepts strive for the truth.

Figure 1.

Knowledge profile of the fundamental sign.

Epistemological basis

SemioticsL

Pragmatic semioticsL

PragmaticismL

FallibilismL

IdealismL

RealismL

PhaneroscopyL

Semiotics of Terminology

Fundamental sign

Consequences

The fundamental sign is L a symbolL

L

As a symbol it developsL according to the hyper-L bolic philosophy of PeirceL

L

It is general and it is realL

L

The meaning of the L fundamental sign resides L in its conceivable conse-L

L quencesL

It is the fundamental signL of any knowledge organi-L zation; hence it organized L all knowledge relatively to L its epistemological basis

510

library trends/winter 2004

A concept’s strive for truth means that the truth of a concept lies in its consequences, and the sum of consequences is the true meaning of the concept.

I believe that the following long quote of Peirce sums up the idealistic, the realistic, and the phaneroscopic angle: idealism being the truth (the meaning) of the concept derived through dialogue and governed by a habit of conduct; realism being the concept’s ability to influence our future conduct, and the habit of conduct equals Thirdness in Peirce’s phaneroscopy.

It is this last element that ensures interpretational stability when speaking of habits of conduct and concepts. Peirce writes:

Since I have employed the word “Pragmaticism,” and shall have occasion to use it once more, it may perhaps be well to explain it. About forty years ago, my studies of Berkeley, Kant, and others led me, after convincing myself that all thinking is performed in Signs, and that meditation takes the form of a dialogue, so that it is proper to speak of the “meaning” of a concept, to conclude that to acquire full mastery of that meaning it is requisite, in the first place, to learn to recognize the concept under every disguise, through extensive familiarity with instances of it. But this, after all, does not imply any true understanding of it; so that it is further requisite that we should make an abstract logical analysis of it into its ultimate elements, or as complete an analysis as we can compass. But, even so, we may still be without any living comprehension of it; and the only way to complete our knowledge of its nature is to discover and recognize just what general habits of conduct a belief in the truth of the concept (of any conceivable subject, and under any conceivable circumstances) would reasonably develop; that is to say, what habits would ultimately result from a sufficient consideration of such truth. It is necessary to understand the word “conduct,” here, in the broadest sense. If, for example, the predication of a given concept were to lead to our admitting that a given form of reasoning concerning the subject of which it was affirmed was valid, when it would not otherwise be valid, the recognition of that effect in our reasoning would decidedly be a habit of conduct. (CP 6.481)

I believe Peirce is saying here that it is necessary to develop a knowledge profile for the concept we investigate. If we fail to recognize the concept under every disguise and if we are unable to make a complete analysis of it, we can investigate the truth of the concept by investigating what habits would ultimately result from a sufficient consideration of such truth. In other words, if we investigate the consequences of the concept, we will reach its fallible truth. In my interpretation, consequences are relations, and tested relations are related terms that can be investigated within a knowledge domain.

Returning to the knowledge profile of the fundamental sign; the four very important concepts (fallibilism, idealism, realism, and phaneroscopy) constrain the concept of the fundamental sign, and it must be understood in relation to these important concepts. Once again we have sharpened the epistemological basis of the fundamental sign. However, it can be sharpened

thellefsen/knowledge profiling

511 even further. The fundamental sign is developed within the concept of semiotics of terminology: to understand the fundamental sign, we must understand the epistemological basis upon which the fundamental sign is developed. We cannot rule out, e.g., the idealistic or the realistic angle.

These aspects are crucial to the understanding of the fundamental sign.

Based on the knowledge profile, we can define the fundamental sign as

• Developed within general semiotics

• Developed within the pragmatic semiotics of Peirce

• Developed within the doctrine of pragmaticism

• Developed in accordance with the fallibilism, the idealism, the realism, and the phaneroscopy of Peirce

• Developed within the semiotics of terminology and part of the SKOmethod.

However, the epistemological basis is only half of the knowledge profile.

The other half consists of the consequences of this epistemological basis.

In the following, we shall take a closer look at the consequences of the epistemological basis trying to complete the knowledge profile for the fundamental sign.

The Fundamental Sign in the Light of Its

Epistemological Basis

In Thellefsen 2002, 2003, and 2004, I have thoroughly defined the fundamental sign. However, to make my points clear, I will briefly define the fundamental sign. The fundamental sign is the central idea of a knowledge domain; it is the historical basis of the knowledge domain that organizes the knowledge in the knowledge domain. The terminology of a knowledge domain is centered around the fundamental sign. Therefore, the fundamental sign is a symbol consisting of and containing the sum of the terms in a knowledge domain. It puts constraints on all the terms so that the terms can only be understood in relation to the fundamental sign. The fundamental sign is an abstract entity, which contains a potential for development.

However, as the consequences of the fundamental sign are learned, the knowledge potential is reduced. I call this process the hardening of the symbol 3 . In the following, I will outline the consequences that make up the fundamental sign based on its epistemological basis.

• In Peircean semiotics, it is sign.

• The meaning of the fundamental sign is identifiable in its related terms.

• Related terms are consequences of the fundamental sign that have been tested and that have become symbols. Consequences, which cannot endure testing, wither away.

• New consequences can alter the knowledge structure of the fundamental sign; hence, knowledge is fallible. In other words, knowledge is provi-

512

library trends/winter 2004

sory. However, since the fundamental sign is a symbol that has grown stable due to the use and experience of the actors in a knowledge domain, only parts of the fundamental sign can alter or else we are dealing with a shift in paradigms and this seldom occurs.

• As a symbol, the fundamental sign is a sign of a particular habit of conduct; namely, the conduct of a given knowledge domain based on its epistemological basis.

• By drawing a knowledge profile, the fundamental sign is identifiable.

The fundamental sign is not the same as a knowledge profile, but it is a sign that develops in accordance with the knowledge profile. The knowledge profile is a method that can be used to identify the fundamental sign.

• Research has shown that the fundamental sign in Danish Occupational

Therapy is activity (Thellefsen, 2002). The meaning of activity is a consequence of a given epistemological basis. To understand the meaning of activity and to identify its KO, it is necessary to draw a knowledge profile for occupational therapy identifying its epistemological basis and to identify the consequences of the epistemological basis.

• Since the fundamental sign is the centre of a KO in a knowledge domain, we must alter our way of conducting KO, that is, if we truly want to represent the KO. If we do not have this intention, we may go on using the classic method, e.g., construction of thesauri and classification schemes.

In summary, in accordance with the knowledge profile method, I have drawn a knowledge profile for the concept “fundamental sign” by outlining its epistemological basis and the consequences of this basis, which leaves us with a well-defined concept.

How to Make the Knowledge Profile

Then how can we use the knowledge profile? In the following six steps,

I generalize the method and make it useful in other situations besides definition of the fundamental sign.

First: Draw the knowledge profile of your concept, your project, or your knowledge domain by identifying its epistemological basis and the consequences of this epistemological basis. Use

Figure 2 as inspiration.

Second: Start by writing the name of your research object (the concept, the problem, the knowledge domain) in the middle.

Third: Consider what theoretical basis you will unfold upon the research object; find the most general state and write it in the outer circle.

This is the most general mode of the theory. In the case of the fundamental sign, this mode was semiotics.

Fourth: Consider how to sharpen this general mode by prefixing or suffixing terms to the concept. In the case of the fundamental sign, I prefixed

“semiotics” with “pragmatic” and got “pragmatic semiotics.” Peirce also did

thellefsen/knowledge profiling

513

Figure 2.

The diagrammatic knowledge profile.

Epistemological basis Consequences

Research object

Knowledge profile this to “positivism,” which he prefixed with “prope,” and defined his pragmaticism as “prope-positivism” (CP 5.412). This is the second circle.

Fifth: Consider whether you can sharpen the concept even further, e.g., by using a subtheory that reduces the knowledge potential of the concept or another theory that may make your concept or project become more precise. In the case of the fundamental sign, I used the doctrine of pragmaticism to narrow down pragmatic semiotics further. This is the third circle.

Sixth: Consider whether you need to sharpen you concept even further, or if you are ready to identify consequences of your concept.

The six steps correspond to the left side of Figure 2, the epistemological basis of the research object. However, to draw a complete knowledge profile, we have to identify the consequences that occur when viewing the research object from a certain epistemological basis as was the case in Figure 1.

Figure 2 functions as a general model for investigating the epistemological basis of a research object, and when this has been done, the next step is to outline the consequences of the epistemological basis to maintain coherence between the epistemology and the way in which the research object is interpreted based on the basis of that epistemology. The knowledge profile helps to keep the project on terminological tracks.

I have neglected to discuss the consequences of the fundamental sign when dealing with KO. Of course, the discovery of the fundamental sign has an important impact on how we shall conduct KO. In fact, I do not believe that librarians and information specialists conduct KO at all since

KO exists prior to any investigation. To assume that KOs do not exist before we organize the knowledge of any knowledge domain would be to dismiss reality and, indeed, it would end in pure nominalism and subjectivism. It would be much more precise to say that we identify KOs and, as a consequence of the identification, we try to make representations of the

KOs. Here, both the knowledge profile and the fundamental sign become

514

library trends/winter 2004

very important. Having drawn a knowledge profile of a knowledge domain and having accepted that the knowledge profile in fact has a considerable influence on the understanding of terms in the knowledge domain (and indeed the KO is organized in accordance with the knowledge profile), then it is time to identify the fundamental sign. The method for identification of the fundamental sign of a knowledge domain is developed in Thellefsen 2002 and Thellefsen 2003 and further elaborated in Thellefsen 2004 and will not be repeated here.

Notes

1 .

I understand a knowledge organization (KO) as the sociocognitive knowledge structure of a given knowledge domain. This means that a KO is the ongoing sociocognitive semiotic processes that take place within a knowledge domain. Indeed, a KO is an abstract entity.

However, it is the terminology of the knowledge domain that is the manifested representation of a KO. Hence, within library and information science (LIS), we do not perform

KO; we make representations of KO, and our task, as I see it, is to develop methods that enable us to make these representations as realistic as possible.

2. Often, thesauri build on bibliometric studies, which primarily build upon statistic terms extracting methods that basically are nonintellectual. The empirical data used to construct thesauri are almost exclusively derived from documents disregarding the impact nonpublished knowledge and tacit knowledge have on the knowledge structures in a knowledge domain.

3. The hardening of symbols refers to the hyperbolic philosophy of Peirce. When the symbol develops, that is, when its consequences are learned, the developmental potential of the symbol is reduced: a hardening of the symbol makes the symbol stable. However, since no one knows the future consequences of a symbol, knowledge cannot be viewed as static; this leaves an amount of unstable potentiality in the symbol.

References

Peirce, C. S. (1931–1966). Collected papers of Charles Sanders Peirce (Vols. 1–8) . (C. Hartshorne,

P. Weiss, & A. W. Burks, Eds.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [(CP) refers to paragraphs in Collected Papers, not page numbers.]

Thellefsen, T. (2002). Semiotic knowledge organization: Theory and method development.

Semiotica, 142 (1), 71–90.

Thellefsen, T. (2003). Semiotics of terminology: A semiotic knowledge profile. SEED Journal,

3 (2). URL: http://www.library.utoronto.ca/see/pages/SEED Journal.html

Thellefsen, T. (2004). The fundamental sign.

Accepted in Semiotica .

Thellefsen, T., Brier, S., & Thellefsen, M. (2003). Problems concerning the process of subject analysis and the practice of indexing: A semiotic and semantic approach towards user oriented needs in document representation and information searching. Semiotica 144 (1),

77–218.