pre-show preparation and activities

-

SHOW PREPARATION

AND

ACTIVITIES

WITH ALIGHNMENTS TO THE COMMON CORE CURRUICULUM STANDARDS

Created by McCarter Theatre Education and Engagement. 2013.

SHOW MATERIALS

2

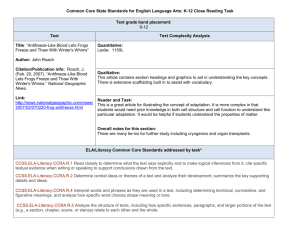

ALIGNMENT TO THE COM

MON CORE CURRICULUM AND CORE CURRICULUM

CONTENT STANDARDS

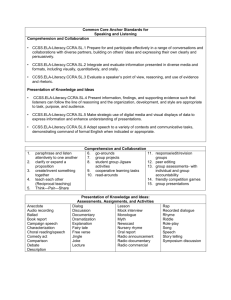

Our production of Proof and the activities outlined in this guide are designed to enrich your students’ educational experience by addressing many Reading, Writing, and Speaking and Listening Common Core anchor standards as well as specific New Jersey Core Curriculum Content Standards for Visual and

Performing Arts. (Click on the titles below to be linked to the activities.)

T HE P ROOF IS IN THE R EADING .

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.1

: Read closely to determine what the text says explicitly and to make logical inferences from it; cite specific textual evidence when writing or speaking to support conclusions drawn from the text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.3

: Analyze how and why individuals, events, or ideas develop and interact over the course of a text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.4

: Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone.

If questions are used for classroom discussion:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.1

: Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.2

: Integrate and evaluate information presented in diverse media and formats, including visually, quantitatively, and orally.

If questions are used for writing prompts:

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.1

: Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.4

: Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.10

: Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of tasks, purposes, and audiences.

O N S IBLINGS , P ARENTS , AND THE T HINGS W E I I NHERIT

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.SL.1

: Prepare for and participate effectively in a range of conversations and collaborations with diverse partners, building on others’ ideas and expressing their own clearly and persuasively.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.4

: Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.10

: Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of tasks, purposes, and audiences.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.3

: Analyze how and why individuals, events, or ideas develop and interact over the course of a text.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.R.4

: Interpret words and phrases as they are used in a text, including determining technical, connotative, and figurative meanings, and analyze how specific word choices shape meaning or tone.

Created by the McCarter Theatre. 2013

.

3

SHOW MATERIALS

VP.1.3.8.C.2

: Create and apply a process for developing believable, multidimensional characters in scripted and improvised performances by combining methods of relaxation, physical and vocal skills, acting techniques, and active listening skills.

I I N C ONTEXT : T HE W HO AND THE W HAT OF

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.2

: Write informative/explanatory texts to examine and convey complex ideas and information clearly and accurately through the effective selection, organization, and analysis of content.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.7

: Conduct short as well as more sustained research projects based on focused questions, demonstrating understanding of the subject under investigation.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.9

: Draw evidence from literary or informational texts to support analysis, reflection, and research.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.10

: Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of tasks, purposes, and audiences.

A T HEATRE R EVIEWER P REPARES .

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.1

: Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.2

: Write informative/explanatory texts to examine and convey complex ideas and information clearly and accurately through the effective selection, organization, and analysis of content.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.4

: Produce clear and coherent writing in which the development, organization, and style are appropriate to task, purpose, and audience.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.CCRA.W.10

: Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of tasks, purposes, and audiences.

Created by the McCarter Theatre. 2013

.

4

SHOW MATERIALS

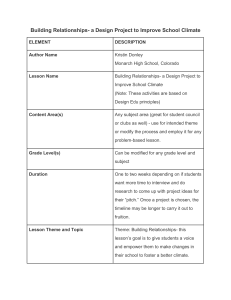

PRE SHOW PREPARATION, QUESTIONS FOR DISC USSION, AND ACTIVITIES

Pick and choose among the following assignments, discussion topics, and activities to introduce your students to David Auburn’s Proof, its theatrical origins and themes, as well as to engage their imaginations and creativity before they see the production.

P ROOF : W EB S ITE B ASICS .

Share the various interviews, articles and information found on McCarter’s Proof web site with your students—preferably by reading them aloud as a class or in small groups—to provide an intellectual and creative context for David Auburn’s elegant and engaging story of passion, genius, and family bonds.

Investigating these various resources will not only pique student interest, but may also spark and fuel fullclass and small-group discussion before coming to the theater.

The activities below will prepare your students to critically consider Proof in performance. We welcome you and your class to read and study the entire play and collectively discuss the questions below. For those only able to incorporate a partial reading of Proof into your class’ pre-show preparation, we suggest utilizing Act

One, Scene Four as your sample scene, complemented with the character profiles provided. We recommend that you and your students read the sample scene in the round—that is, instead of casting the three roles among only three students, have all students read from the play with the next student taking on the next character’s line of dialogue—so that each student gets to “try on” the character and voice of each character in the scene. After reading the scene aloud, engage students in a discussion of the scene, its characters, and the developing story. Questions might include:

With which character do you most identify and why?

With which character do you most empathize or sympathize in the scene? Upon what is your empathy or sympathy based?

Describe—in three words—what you learn about the following relationships in the course of the scene:

Catherine and Claire

Catherine and Hal

Hal and Claire

Catherine and Robert (her father)

Hal and Robert

Claire and Robert

How would you describe the tone of this scene? What type of atmosphere is created by the characters and their interactions?

Did you notice anything that stood out to you in the words spoken by each character or about their character voices in general? Do Auburn’s characters have distinct voices? If so, how are they distinct? What do their voices say about them?

What do the characters want from each other? What do they want from or for themselves? If they had to choose to live their lives to obtain either love, wealth, fame, or power, which do you think they would choose?

Scene 4 is the last scene before an intermission. How do you think it affects the audience to be left with Catherine’s revelation immediately before taking a moment away from the world of the play?

Cr

SHOW MATERIALS

5

O N S IBLINGS , P ARENTS , AND THE T HINGS W E I I NHERIT .

When David Auburn began to write Proof , he didn’t start with the idea of writing a play about mathematics or mathematicians. Instead his dramatic idea was grounded in an exploration of the relationship between two sisters and a conflict over something they have found. As is often the case in family dramas, an object might be the basis for or cause of a conflict (a coin collection, a letter, a house), but what is truly at stake in domestic drama isn’t the object, but the making or breaking of a relationship—or the family itself.

The story of Proof focuses largely on two familial relationships at critical junctures—the relationship between siblings (specifically two sisters, Catherine and Claire) and the relationship between a parent and a youngadult child (a father and a daughter, Robert and Catherine)—and on the theme of inheritance; a question central to the story of the play is “What do we inherit from our parents?”

Share the above information on Proof’s central relationships and theme with your students, and then lead them in a discussion on the dynamic nature of siblings. Questions might include:

What are the first things that come to mind when you think of sibling relationships? (You might employ the classroom board as a place to brainstorm or create a word cloud.)

What are common conflicts among siblings?

Do you think that the gender of siblings determines or influences the nature of conflicts? Does gender make a difference? (For example: Are typical brother-sister conflicts the same or similar to sister-sister or brother-brother conflicts?) How does age impact sibling relationships/conflicts?

Do you think conflicts change or evolve among siblings as they get older? If yes, what do you think accounts for the evolution? If no, what do you think accounts for a lack of evolution or development?

How many of you have siblings? How many of you are the oldest? How many the youngest?

How many are “in the middle?” How many of you are only children? Are there any particular joys or challenges to being: the oldest, the youngest, the middle child, or an only child? Name them.

Next have your students contemplate—via journal writing—parent-child relationships and the theme of inheritance as they pertain to their own lives. Inform your students in advance as to how their journal entries will be used to encourage them to write truthfully and privately, or, if their writing will be shared, to give them the opportunity to edit their thoughts. Journaling prompts might include:

Do you come from a family or know of a family in which there seems to be a “favorite kid?” Upon what circumstances or considerations has this favorite status been founded or granted? Do you think favoritism is given or earned? What do you imagine life is like as the favorite child? What do you imagine life is like for the non-favored child?

Think about the adult in your life who you consider to be your closest parental figure and describe the nature, depth, and quality of your bond with him or her. What sort of parental figure do you yourself hope to become?

List and describe the gifts, traits, lessons, or circumstances have you inherited from a parent or family that you are grateful to have received. (Consider things of both a tangible/material and intangible/nonmaterial nature.) What gifts, traits, lessons, or circumstances do you hope to pass onto your own children or those closest to you?

Consider the things you have inherited or may inherit from a parent or your family could be cause for conflict, stress, worry or fear. Are there ways that you might avoid or overcome these challenging aspects of your inheritance?

Any aspect of the discussion or journaling work above can be used as inspiration for a short story, a dramatic scene, or a visual art project, although journals should remain private unless previous notice was given.

Created by the McCarter Theatre Education Department. 2013

.

SHOW MATERIALS

6

Getting a play and its characters up on their feet is an excellent way for students to personally experience the playwright’s craft and explore the world and characters of the play themselves before seeing the play brought to life in performance. Have your students study excerpted dramatic moments from David Auburn’s Tony Award and

Pulitzer Prize-winning play Proof.

Widely available editions of the play include the Faber and Faber edition (2001) and an acting edition published by Dramatist Play Service (2001). We suggest the following “French scenes”/ dramatic interactions from the play:*

#1 The opening moment of the play—Act One, Scene One—between

Robert and Catherine, beginning at the top of the play and ending with

Robert’s line, “Don’t waste your talent, Catherine.”

#2 The middle of Act One in a moment between Catherine and Hall, beginning with Hal’s entrance and Catherine’s line “What?” and ending with Hal’s line “I met your dad and he put me on the right track with my research. I owe him.”

#3 A few pages into Act One, Scene 2 with Claire and Catherine beginning with Claire’s line “Katie, some policemen came by while you were in the shower,” and ending with Catherine’s line “Oh I don’t remember.”

#4 A few pages into Act Two, Scene One with Robert, Hal, and Catherine beginning with Hal’s entrance and Robert’s line “Mr. Dobbs,” and ending with Robert’s “Enjoy yourself, see some movies,” and Hal’s “Okay.”

First, if you haven’t already, share the articles and interviews included in the McCarter Proof web site with your students, including the Character Profiles .

You might choose to read the excerpted “scenes” together as a class for comprehension and audition. (Reading in the round and alternating lines will give each student a chance to try out the speech and voices of different characters). Some words or phrases may need to be defined or explained; a “Mostly Math” Glossary is available under the “Educators” tab on the Proof web site..

Next, break your class up into scene-study duos and trios. Groups of two should work on excerpt

#1 (Robert and Catherine), #2 (Catherine and Hal), and #3 (Claire and Catherine) and groups of three on excerpt #4 (Robert, Hal, and Catherine).

Scene-study groups should read their scene aloud together once before getting up to stage it, to get a sense of the characters and the scene overall.

Student-actors should prepare/rehearse their scene for a script-in-hand performance for the class.

Following scene performances, lead students in a discussion of their experience rehearsing and performing Questions might include:

What are the pleasures and challenges of performing your scene from David

Auburn’s Proof ?

What insights, if any, regarding the play or the characters did you get from staging the play and playing the characters?

What about your character felt real and/or relatable to you in the acting of him or her?

Was there any moment that felt strange or awkward in bringing your character to life? Explain your reaction.

Was there a moment that felt especially compelling or fun to bring to life?

Explain your reaction.

*Note that Proof is a contemporary American play and that its characters occasionally use expletives. Educators should read each scene excerpt before assigning to students.

Created by McCarter Theatre. 2013

.

SHOW MATERIALS

7

I I N C ONTEXT : T HE W HO AND THE W HAT OF

To prepare your class for Proof and to deepen their knowledge and level of understating of the play’s distinctive world and its characters, have them research, either in groups or individually, the following topics:

Playwright David Auburn

The world-premiere production of Proof

A comparison of Broadway’s Catherines: Mary Louise Parker, Jennifer Jason Leigh, and Anne

Heche as Proof’s Catherine

Proof on film

Director Emily Mann

The life of a mathematician

Mathematical proof (defined)

Fermat’s Last Theorem

Sir Andrew Wiles

G.H. Hardy’s A Mathematician’s Apology

Sophie Germain

The link between genius and mental illness—fact or fiction?

Geniuses who suffered from mental illness

John Nash

Vincent Van Gogh

Ludwig van Beethoven

Edgar Allan Poe

Have your students teach one another about their individual or group topics via oral and illustrated (i.e., posters,

PowerPoint, or Prezi) reports. Following the presentations, ask your students to reflect upon their research process and discoveries.

A T HEATER R EVIEWER P REPARES .

A theater critic or reviewer is essentially a “professional audience member,” whose job is to report the news, in detail, of a play’s production and performance through active and descriptive language for a target audience of readers (e.g., their peers, their community, or those interested in the Arts). To prepare your students to write an accurate, insightful and compelling theater review following their attendance at the performance of Proof, prime them for the task by discussing in advance the three basic elements of a theatrical review: reportage, analysis and judgment.

Reportage is concerned with the basic information of the production, or the journalist’s “four w’s” (i.e., who, what, where, when), as well as the elements of production, which include the text, setting, costumes, lighting, sound, acting and directing (see the Theater Reviewer’s

Checklist ). When reporting upon these observable phenomena of production, the reviewer’s approach should be factual, descriptive and objective; any reference to quality or effectiveness should be reserved for the analysis section of the review.

With analysis the theater reviewer segues into the realm of the subjective and attempts to interpret the artistic choices made by the director and designers and the effectiveness not of these choices; specific moments, ideas and images from the production are considered in the analysis.

Judgment involves the reviewer’s opinion as to whether the director’s and designers’ intentions were realized, and if their collaborative, artistic endeavor was ultimately a worthwhile one. Theater reviewers always back up their opinions with reasons, evidence and details.

Remind your students that the goal of a theater reviewer is “to see accurately, describe fully, think clearly, and then (and only then) to judge fairly the merits of the work” (Thaiss and Davis, Writing for the Theatre ,

1999). Proper analytical preparation before the show and active listening and viewing during will result in the effective writing and crafting of their reviews.

Created by the McCarter Theatre. 2013

.