Nurse Education in Practice (2008) 8, 412–419

Nurse

Education

in Practice

www.elsevier.com/nepr

Holistic practice – A concept analysis

Liz McEvoy a, Anita Duffy

a

b

b,*

AMNCH, Tallaght, Ireland

Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, RCSI, Dublin, Ireland

Accepted 10 February 2008

KEYWORDS

Summary

Concept analysis;

Holism;

Holistic;

Body, mind and spirit;

Nursing practice

Aims and objectives: This article aims to clarify the concept of ‘‘holism’’ in nursing

through the use of Rodgers [Rodgers, B.L., 1989. Concept analysis and the development of nursing knowledge; the evolutionary cycle. Journal of Advanced Nursing 14,

330–335] concept analysis framework.

Background: The primary author is employed in a urology department which cares for

many clients with end stage cancer. Holistic nursing practice is the philosophy of the

unit, however many nurses struggle to articulate what holistic practice actually means

to them, hence this analysis was deemed very pertinent to practicing nurses to enable

the realization of nurses therapeutic potential when caring for patients in practice.

Method: Rodgers (1989) well-established method of concept analysis was employed

to facilitate the clarification of the concept of holistic nursing practice.

Relevance to clinical practice: The clarification of the concept offered a working definition of holistic nursing practice which practicing nurses can clearly comprehend and

avail of when caring for patients of all race, religion and creed in the clinical practice

area.

Conclusion: By undertaking this methodology of concept analysis the integrity of the

concept was kept intact. The factors that influence holistic nursing practice were

identified and a model case demonstrated the reality of holistic nursing care for practicing nurses.

c 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Concept analysis is viewed by many as a method for

clarifying overused or vague concepts (McBrien,

2006). As concepts such as ‘‘holism’’ are often sub* Corresponding author. Tel.: +353 1 4028643.

E-mail address: aniduffy@rcsi.ie

jective, it is important that their meaning is clarified, otherwise misuse can dilute their relevance

to practice. Additionally, having concrete definitions assist in implementing the term in question

into practice ultimately supporting research and

theory development (Paley, 1996; Villagomeza,

2005; McBrien, 2006) vital for the professional

development of nursing.

1471-5953/$ - see front matter c 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2008.02.002

Holistic practice – A concept analysis

The purpose of this article was to clarify the

concept of ‘‘holism’’ utilising Rodgers (1989) evolutionary concept analysis approach. In order to enhance the comprehension of the concept of

‘‘holism’’, it was necessary to identify the attributes, antecedents and consequences over an extended period of time. The authors critically

analysed the concept and its application to practice through describing a true life model case of

holistic nursing practice. The article concludes

with a clear definition of holism to offer practicing

nurses an understanding of the reality of holistic

nursing care.

Nursing knowledge

Theories are applied to nursing in the form of nursing models which are then adapted and applied to

the particular clinical setting. The development

and refinement of theories creates new quality approaches to care and challenges existing practice

(Wadensten and Carlsson, 2003). Nursing is both

practice and academically based, therefore in order to create new approaches to practice, knowledge is essential. Knowledge must not only be

about the empirics, but also about the how and

why of practice. This, according to Carper (1978)

is what separates nursing from other disciplines.

There are many controversial debates in the

nursing literature concerning the professionalisation of nursing. It is agreed that one of the accepted hallmarks of a profession is the possession

of a unique body of knowledge (Leddy and Pepper,

1993). It is not the possession, but the application

of this knowledge to practice that makes nursing

unique. Building on both practical and propositional knowledge is crucial to assist nurses’ develop

nursing theory that can be applied to practice (Colley, 2003). Walker and Avant (1995) state that concept analysis is the first step of theory

development to clarify and define the phenomenon

in question. Clarifying nursing concepts has the

advantage of empowering nurses and furthermore

it facilitates professional autonomy, which ultimately results in the professional development of

nurses (Ingram, 1991).

However, it is naive and misleading to describe

nursing knowledge as unique-as no single discipline

has exclusive ownership over knowledge. Never the

less, nursing does claim to have a unique focus on

caring, understanding and knowing the whole person (Brockopp and Hasting-Tolsma, 2003). Colley

(2003) argues that knowledge borrowed from other

disciplines only serves to dilute nursing practice,

whilst Junor et al. (1994) argues that shared know-

413

ledge through team work is known to maximise

clinical effectiveness. There is a need to reassess

exclusive claims to specialist knowledge and

authority in order to provide the best possible care

to individual patients. Teams need to have shared

goals and values to understand and respect the

knowledge of other disciplines. In addition Carrier

and Kendall (1995) identify that holistic care will

only be met if there is a readiness to share knowledge and surrender exclusive claims to specialist

knowledge and authority.

It therefore follows that there is no such thing as

unique knowledge and that borrowed theories only

result in enhancing nursing practice (Bradshaw,

1995). This is particularly applicable to holism

and holistic theories, which address the whole person, including mind, body and spirit, cultural,

social and environmental approaches to care.

Therefore, it is inevitable, that knowledge from

other social sciences is considered. The fact that

healthcare is continually evolving with an increased focus on interdisciplinary team work, further enhances this debate. Hence, a balance must

be found considering other health disciplines have

as much to learn from nursing as nursing has from

them. By working together and sharing knowledge

disciplines begin to understand each other’s perspectives and learn and grow in their own practice.

Concept analysis

Concepts have been described by McKenna (1997:8)

as ‘‘the building blocks of theory’’. Paley (1996)

further argued that there is no agreement as to

what constitutes a concept. Concepts are like ice

cubes; just when you think you have grasped them,

a lack of clarity results in their slipping beyond your

grasp. They must therefore be analysed before

they are misused in theory development. The aim

of this analysis was to advance the concept of

‘‘Holism’’ for theory development. In order to do

so, a qualitative enquiry to create meaning through

language, was deemed necessary.

Whilst there are a number of frameworks available for concept analysis, Rodgers (1989) qualitative approach was chosen. Rodgers (1989)

framework presents an inductive, dynamic view

of phenomenon (Cutliffe and McKenna, 2005) as

opposed to that of Walker and Avant’s (1995)

framework, which offers a more restrictive, deductive, quantitative examination (Rodgers, 1989).

Walker and Avant’s (1995) method of analysis is

in contrast to the philosophy of holism and therefore was deemed inappropriate. Holism as a concept is nebulous and subjective, captivating

414

L. McEvoy, A. Duffy

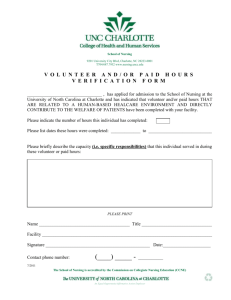

Identify concept of interest

Identify Surrogate terms

the authors researched textbooks in both medical

and public libraries which provided useful information for this analysis. Many articles were discarded

as they were vague, anecdotal and ambiguous.

Articles that were used (n = 27) either defined holism or gave a plausible account of how ‘‘holism’’

was demonstrated in nursing practice.

Data collection

Holism

Analysis of Data

Identify the attributes of the concept

Identify references, antecedents and consequences

Model case

Figure 1

analysis.

Rodgers (1989) framework for concept

nurses over many centuries, with its application to

practice changing over time. This further supported the use of Rodgers (1989) method which

acknowledges that concepts are influenced by significance, use and application over time, resulting

in an analysis that is more practise related and current (Baldwin, 2003). Cutliffe and McKenna (2005)

additionally defend the real life evolutionary approach to concept analysis which uses a real life

model case to demonstrate the attributes, antecedents and consequences of the concept. Other

model cases such as the deviant or borderline cases

as proposed by Walker and Avant’s (1995) model is

not within Rodgers philosophy, hence they were

not incorporated. Cahill (1996) advises authors to

be aware of the philosophical approaches of the

chosen concept analysis framework. Fig. 1 outlines

the steps in Rodgers (1989) framework.

Literature search

A review of the relevant literature, derived from

the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health

Literature (CINAHL), Medline and Pub Med – using

the keywords ‘‘holism’’, ‘‘holistic’’ and ‘‘body,

mind and spirit’’ was undertaken (n = 126). The

word ‘‘spirit’’ was used rather than ‘‘soul’’ as

the authors believe soul and spirit are interchangeable terms for our immaterial selves. Additionally,

Holism derives from the Greek word ‘‘holos’’,

meaning whole (Griffen, 1993). Healing and health

stem from the Greek word ‘‘hale’’ which also

means to make whole (Kenney, 2001). Therefore

holism, healing and health are inter-related concepts in the nursing literature. With this in mind

it became evident that the concept of ‘‘holism’’

required clarification to extricate holism from

health and healing.

While most definitions of holism share the same

attributes, it is the application to practice that has

led to much discourse. Nursing is indeed holistic in

nature, as the nursing profession has traditionally

viewed the person as a whole, concerned with

the interrelationship of body, mind and spirit, promoting psychological and physiological well-being

as well as fostering socio-cultural relationships in

an ever changing economic environment of care.

However, holism is not exclusive to nursing and

has been used in banking, where holism is a practice of looking at the various factors that lead people to invest (Wilber and Harrison, 1978). Also, the

Montessori teaching method is based on a concept

of ‘‘holism’’ (Infed, 2005).

Smuts (1870–1950), a South African soldier and

philosopher introduced the word ‘‘holism’’ from

the language of chemistry and in his book ‘‘Holism

and Evolution’’ defined ‘‘holism’’ as, ‘‘. . .the principle which makes for the origin and progress of

wholes in the universe’’ (Smuts, 1926). This philosopher believed that the whole was greater than the

sum of its parts, explaining how South Africa was

greater in its entirety rather than its individual

states. These thought patterns can be further

traced to the Gestalt psychologists of 1920s and

1930s who also believed the whole was greater

than the sum of its parts.

It was in the 1970s that nursing became influenced by the concept of ‘‘holism’’, guided by

humanistic theorists such as Rogers (1970) ‘unitary

nature of human beings’. Rogers believed that the

world is a single whole in which every element is

interconnected with others. In 1971, Levine further

described the role of the nurse as viewing each patient as a unique human being in contrast to the

Holistic practice – A concept analysis

reductionist approach of medicine. Early theorists

such as Rogers (1970) and Levine (1971) describe

patients in terms of the wholeness. Ham-Ying’s

(1993) analysis envisioned two common usages of

holism in nursing – a personal view and an approach to nursing care. The American Holistic

Nurses Association (1992) defined ‘‘holistic nursing’’ as, ‘‘. . . that state of harmony between mind,

body, emotions and spirit in an ever changing environment’’. This perspective is consistent with the

contemporary view of ‘‘holism’’ in nursing, where

the physical, social, cultural and spiritual realms

are interconnected (Govier, 2000; Jackson, 2004;

Smart, 2005). These aspects are incorporated into

Leininger’s theory (1988) where diverse cultures

and religions are taken into account, which is particularly apt in modern healthcare and society. It

could be argued that holism was always the approach of nursing but it was the theorists that put

it into words.

To practice holism, nurses are recommended to

be aware of both their own potential wholeness

and also that of the patient. Our sense of wholeness depends on our own vulnerability and on the

opinions of other (Bright, 1997). Self-awareness is

important and through the artful use of self,

whereby an individual strives toward achieving a

sense of balance within oneself and the world, often achieved through reflective practice; harmony

can enter relationships (Cumbie, 2001). It takes

personal, intellectual and professional maturity to

reach this level of self awareness and personal harmony. In practice, nurses who display the defining

attributes of holism, discussed further in this analysis, are guided by past experience and intuition

(Benner, 1984). The degree of harmony that exists

between nurses and their patients is central to

holistic nursing.

The heart of holistic nursing is helping empower

the patient to utilize their inner resources to improve their quality of life and adapt to changes

caused by the disease trajectory (Buckley, 2002).

The concept of empowerment is frequently used

in nursing, particularly in relation to quality of

care, since the mission of nursing is to provide safe

and quality nursing care, thereby enabling patients

to achieve their maximum level of wellness. The

role of nursing has evolved from being a guardian

to being a creator of empowerment and over the

last decade the generic role of the nurse has been

replaced by the specialist nurse. The changes in

nursing has expanded the role to include increasing

emphasis on health promotion and illness prevention, as well as concern for the patient as a whole.

A difficulty for nurses achieving holistic care may

be due to the strong emphasis placed on ‘‘interdis-

415

ciplinary’’ nursing. While acknowledging the expertise of specialist nurses, it could be argued that

what essentially has happened is that specialism

has fragmented the whole back into its component

parts. In terms of concept analysis, the word ‘‘holism’’ has gone full circle. To practice holism as referred to in the Scope of Practice (An Bord

Altranais, 2000), where nurses are required to expand their practice to become more competent,

developing reflectice practice skills, expertise

and clinical skills in order to meet the patients

needs in a holistic manner, nurses must use their

discretion and work within a defined framework

to provide the patient with a truly holistic approach to care rather than fragmenting the care

into bio/social/psycho sub-systems. To overcome

this effect there must be a way of providing holistic

care through shared philosophies amongst interdisciplinary professionals.

Frankl (1984) claimed that characteristics of a

holistic approach to care are the individual’s primary motivational force to search and find meaning

in life. However, many people do not feel the need

for such a psychological approach to care, considering it as intrusive (Griffen, 1993; Smart, 2005).

Many patients in the primary authors clinical practice area – a urology department- are male, over

the age of 65 and do not welcome a holistic approach for this precise reason. In this authors’

experience, men tend to place greater value on

the physical aspects of care, such as assistance

with catheter care and wound care. However, it

is important not loose sight of the psychological,

spiritual, cultural, and social aspects of nursing

care, balancing nursings’ contribution, with all

dimensions of care taken into account, as all too

often, nurses can also be overly focussed on the

physical aspects of care. The rapid patient turnover in the urology department should not be used

as an excuse to neglect holistic care. Spiritual care

can be achieved simply by being present or through

attentive listening (DiJoseph and Cavendish, 2005).

However brief the moment, the authors concur

with Jackson (2004), who believes that spiritual

care can have a profound effect on the patient’s

well-being and also on the nurse in terms of job

satisfaction (Nichols, 1992). ‘‘There is little point

in curing the body if we destroy the soul’’ (Anon

in Martsolf and Mickley, 1998). Being spiritual does

not mean saintly or affiliated with a particular religion (Buckle, 1993; Govier, 2000; Jackson, 2004)

Very often, those who opt for a less formal approach to spirituality can achieve inner harmony

(Narayanasamy, 1999). For many, the more formal

approach is taken, with prayer being the most frequently used spiritual practice among all cultures

416

(DiJoseph and Cavendish, 2005). Research claims

that when people are ill they resort to such practices (Meraviglia, 1999). Indeed, research into the

effect of prayer has demonstrated the positive effects of prayer, in terms of life expectancy in both

AIDS and cancer patients not only when they said

prayers themselves but also when they were prayed

for (Byrd, 1988; Harris et al., 1999; DiJoseph and

Cavendish, 2005). As a consequence of the limited

amount of exposure to spirituality in education and

practice, nurses often lack the confidence to

broach spiritual issues with patients (DiJoseph

and Cavendish, 2005; McSherry, 1998). Therefore,

education to support spiritual outcomes in nursing

programmes must be enhanced and considered in

the nursing curriculum (Belcher and Griffiths,

2005). In today’s climate there are an increasing

number of both patients and staff from different

religious backgrounds. Understanding the concept

of holistic care therefore requires sensitivity and

knowledge of the beliefs of the patient, in the context of his or her own lived values.

Defining attributes

Attributes of a concept are the characteristics of

that concept that appear time and time again in

the literature. The attributes of ‘‘holism’’ identified by this concept analysis are ‘‘mind, body and

spirit’’ ‘‘whole’’ and ‘‘harmony’’ (Buckle, 1993;

Griffen, 1993; Ham-Ying, 1993; Owen and Holmes,

1993; Kolcaba, 1997; Cumbie, 2001). These are in

line with the more traditional approaches to the

concept of ‘‘holism’’ commonly found in the

1990s. However, a more recent paradigm now considers ‘‘healing’’ as a defining attribute of ‘‘holism’’ (Cowling, 2000; Wong and Pang, 2000;

Buckley, 2002; Ernst, 2004; Jackson, 2004).

Antecedents and consequences

The identification of antecedents and consequences are an important part of any concept analysis as they provide further clarity regarding the

concept of interest (Rodgers, 1989). Antecedents

are events that take place prior to the occurrence

of the concept, and consequences happen as a result of the concept (Rodgers, 1989). For holism to

take place an authentic nurse/patient relationship,

built on mutual trust and understanding is necessary

(Cumbie, 2001). The nurse requires knowledge,

expertise and good effective communication skills

(Olive, 2003).

L. McEvoy, A. Duffy

Table 1 Antecedents and consequences of holistic

nursing care

Antecedents for patient

Need

Relationship

Communication

Illness

Disharmony

Caring environment

Autonomy

Self empowerment

Antecedents for nurse

Assessment of need

Relationship

Communication

Intuition

Knowledge

Advocacy

Accountability

Environment conductive

to caring

Consequences positive

for patient

Harmony

Healing

Empowering

Consequences positive

for nurse

Self-satisfaction

Increased job satisfaction

Increased personal

development

Professional development

Increased personal

development

Consequences negative

for patient

Intrusive

Can focus too much on

psychological

Consequences negative

for nurse

Emotionally draining

Time consuming

There are both positive and negative consequences for the patient and the nurse (described

in Table 1) Positive consequences for the nurse include personal and professional development. This

outcome can result in a more substantive meaning

of job satisfaction. For the patient holistic care can

result in better patient outcomes by building on patient’s inner strength (Villagomeza, 2005) and the

creation of a person centred health system as

described in the Health Strategy (Department of

Health and Children, 2001) as one which identifies

and responds to the needs of the individual, is

planned and delivered in a coordinated way, and

helps individuals to participate in decision making

to improve their health.

A negative consequence for the patient is intrusion, hence holistic care must be patient led to

avoid intrusion. In patients who do not know their

needs, such as the unconscious patient, patients

with mental health problems or the ill neonate,

the use of the nurse’s antecedent skills, such as

intuition, effective nurse-patient relationships,

advocacy, and accountability all come into

effect. Equally, for some nurses, the consequences of providing twenty four hour holistic care

can be exhausting leaving the nurse emotionally

drained.

Holistic practice – A concept analysis

Surrogate terms

Surrogate terms appear to be related to the

concept of holism but not the same and include concepts such as ‘‘complimentary’’ and ‘‘alternative’’

(Buckle, 1993; Barraclough, 2001). Words such as

‘‘oneness’’, ‘‘inseparable’’ and ‘‘interconnected’’

are also used in synonymously with holism (Patterson, 1998; Barraclough, 2001).

Model case

Liz, the primary author, reflected on an incident

she was involved in, which she felt reflected a

holistic approach to patient care:

‘‘Jim and I chatted away together while I assisted

with his daily wash (harmony).He told me, about

his life and following a rather informal conversation he expressed how he would love ‘‘to go’’

tomorrow, – the Feast of the Immaculate Conception’’. Initially I was struck by the change in direction of the conversation, but I knew it was essential

for Jim that I took the time to listen to him. We

talked candidly about what prayer and life after

death meant to each of us (spirit).I sat down beside

him and I felt the need to hold his hand and listen

(body and mind).

Following our deep conversation (body, mind and

spirit), I noticed he needed his toe-nails cut

(body) It is our practice to call the chiropodist

but instead, I said ‘‘Jim would you like your nails

done?’’ ‘‘That would be lovely. . . but Id like you

to do it, if you have the time’’ he replied, smiling

(harmony and healing) and added ‘‘it will be a

while before I get them done again’’ After I finished, I enquired if he would like to see Sr. Lucy

from Pastoral Care (spirit, healing). ‘‘No, thank

you dear, I’m refreshed in every sense of the

word,, much better now after talking to you’’

(wholeness, body, mind and spirit, harmony

and healing). I left with a sense of satisfaction

knowing that I had contributed to the final

moments of his life, but overwhelmed by our frank

conversation about his impending death. Jim died

that night; the night nurses said he died

peacefully.

The model case is a true account of Liz nursing

relationship with a patient who was facing death.

The model case touches on many of the key attributes of holism identified through this analysis such

as assessment of need, effective nurse patient

relationships, and intuition. The harmonious relationship between the pair, allowed Jim share his

417

thoughts while he prepared for his final transition

to death.

The case demonstrates the therapeutic nursing

relationship that existed between the practitioner

and her patient, which encompassed the patients

mind, body and spirit to achieve wholeness, harmony and healing whilst attending to the patient’s

daily activities of living in a holistic nursing manner. Liz felt that in some way- perhaps simply from

her presence, she had eased Jim’s mental suffering. This caring relationship involved the therapeutic use of self within the human–human encounter

(Johns, 2004). By cutting his toe-nails herself,

rather than referring him to the chiropodist, Liz

had refrained from fragmenting Jims care, thus

affording Jim holistic nursing care. The holistic

care given in this model case offered Jim mental,

bodily and spiritual care which resulted in harmony, healing and wholeness. Liz was enabled to

spend this valuable time with Jim in a culture that

values holistic caring by putting the patient

first.

Impact on nursing education and

practice

Nurses, whether specialists or generalist practitioners must respond sensitively to the patient’s spiritual and cultural belief systems, demonstrating

caring, presence and integrating spirituality into

the nursing care plan in order to meet the needs

of the patient in a holistic manner. More emphasis

should be placed on the concept of holism and

holistic practice in nurse education and practice

in order to treat individual’s social, cognitive,

emotional and physical problems. Holistic nursing

is a complete way to practice professional nursing

(Montgomery Dossey et al., 2005) hence, holistic

nursing must be integrated into the nurse education curriculum. Holistic nursing draws on nursing

knowledge, theories, expertise and intuition, all

of which can be developed through reflective practice. A paradigm shift is required to embrace holistic nursing. Nursing need to be committed to the

core values of caring, critical thinking, holism,

nursing role development and accountability.

These values focus on the key stakeholders in

health care- the clients, their families and the allied health care teams involved in patient care.

The achievement of these five core values is essential to form the foundation in order to practice the

art and science of nursing in a holistic manner.

Nurse specialisation should not fragment the

whole. Post graduate nurses should be encouraged

418

to undertake further education to develop skills,

competence and expertise in clinical practice.

The provision of stand alone modules in specialist

nursing care is perhaps one answer to encourage

holistic nursing care in the future. Furthermore,

interdisciplinary education, where scientific knowledge is shared amongst allied professionals could

ultimately lead to mutual understanding and application of holistic care to practice. An all for one

and one for all ‘‘Musketeer’’ approach to health

care education may be the solution to the challenges of providing holistic patient care with more

emphasis placed on the development of teambuilding skills and the development of a collaborative approach to patient care.

Conclusion

Concepts are a means through which nursing care

can be articulated. Concept analysis can be a very

effective way of ensuring that the integrity of a

concept is maintained, even as the boundaries of

knowledge and practice become more permeable.

One surprising outcomes of this concept analysis

was that the term ‘‘holism’’ has been linked to the

concept ‘‘interdisciplinary’’. It emerged in this

analysis that interdisciplinary care can fragment

patient care. A current focus on nursing is the

advancement of nursing practice and encouragement of nurse specialisation. Is nursing looking at

the trees instead of the forest? Adjustments need

to be made, so that nurses can view and appreciate

the landscape in its entirety rather than focussing

on isolated parts. Then, and only then, the scene

can be re-set for ‘‘holism’’ and holistic practice

in its purest sense.

In conclusion a working definition of ‘‘holistic

nursing practice’’ is hereby offered by the authors:

‘‘Holistic nursing care embraces the mind, body

and spirit of the patient, in a culture that supports

a therapeutic nurse/patient relationship, resulting in wholeness, harmony and healing. Holistic

care is patient led and patient focused in order

to provide individualised care, thereby, caring

for the patient as a whole person rather than in

fragmented parts.’’

References

American Holistic Nurses Association, 1992. <http://www.ahna.org/about/statements.html#ethics> (accessed 08.08.07).

An Bord Altranais, 2000. Review of Scope of Practice for Nursing

and Midwifery: Final Report, An Bord Altranais, Dublin.

L. McEvoy, A. Duffy

Baldwin, M.A., 2003. Patient advocacy: a concept analysis.

Nursing Standard 17 (21), 33–39.

Barraclough, J., 2001. Integrated Cancer Care Holistic, Complementary and Creative Approaches. Oxford University,

Oxford.

Belcher, A., Griffiths, M., 2005. The spiritual care perspectives

and practices of hospice nurses. Journal of Hospice and

Palliative Nursing 7, 271–279.

Benner, P., 1984. From Novice to Expert Excellence and

Power in Clinical Nursing Practice. Prentice Hall, Menlo

Park.

Bradshaw, A., 1995. What are nurses doing to patients? A review

of theories of nursing past and present. Journal of Advanced

Nursing (4), 81–92.

Bright, R., 1997. Wholeness in Later Life. Jessica Kingsley

Publishers, Pennsylvania.

Brockopp, D., Hasting-Tolsma, M.T., 2003. Fundamentals of

Nursing Research Sudbury. Jones & Bartlett Publishers,

Massachusetts, USA.

Byrd, R.C., 1988. Positive therapeutic effects of intercessory

prayer in a coronary care unit population. Southern Medical

Journal 81, 826–829.

Buckle, J., 1993. When holism is not complementary. British

Journal of Nursing 2 (15), 744–745.

Buckley, J., 2002. Holism and a health-promoting approach to

palliative care. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 8

(10), 505–508.

Cahill, I., 1996. Patient participation: a concept analysis.

Journal of Advanced Nursing 24, 561–571.

Carper, B., 1978. Fundamental patterns of knowing in nursing.

Advances in Nursing Science 1 (1), 13–23.

Carrier, J.M., Kendall, I., 1995. Professionalism and interprofessionalism in health and community care; some theoretical

issues. In: Owens, P., Carrier, J., Horder, J. (Eds.), Interprofessional Issues in Community and Primary Health Care.

Macmillan, London.

Colley, S., 2003. Nursing theory: its importance to practice.

Nursing Standard 17 (46), 33–37.

Cowling, W.R., 2000. Healing as appreciating wholeness.

Advances in Nursing Science (March), 16–33.

Cumbie, S.A., 2001. The integration of mind–body-soul and the

practice of humanistic nursing. Holistic Nursing Practice 15

(3), 56–62.

Cutliffe, J.R., McKenna, H.P., 2005. The Essential Concepts of

Nursing Building Blocks for Practice. Elsevier Churchill

Livingstone, Edinburgh.

Department of Health and Children, 2001. Quality and Fairness:

A National Health Strategy, Stationery Office, Dublin.

DiJoseph, J., Cavendish, R., 2005. Expanding the dialogue on

prayer relevant to holistic care. Holistic Nursing Practice 9

(4), 147–154.

Ernst, L., 2004. Polarity addresses the ‘‘Whole’’ in holistic.

Holistic Nursing Practice 18 (2), 63–66.

Frankl, Viktor, 1984. Man’s Search for Meaning. Washington

Square Press.

Govier, I., 2000. Spiritual care in nursing: a systematic

approach. Nursing Standard 14 (17), 32–36.

Griffen, A., 1993. Holism in nursing: its meaning and value.

British Journal of Nursing 2 (6), 310–312.

Ham-Ying, S., 1993. Analysis of the concept of holism within the

context of nursing. British Journal of Nursing 2 (15), 771–

774.

Harris, W.S., Gowda, M., Kolb, J.W., Strychacz, C.P., Vacek,

J.L., Jones, P.G., 1999. A randomized, controlled trial of the

effects of remote, intercessory prayer on outcomes in

patients admitted to a coronary care unit. Archives of

Internal Medicine 159, 2273–2278.

Holistic practice – A concept analysis

Infed, 2005. A brief introduction to holistic education. www.infed.org/biblio/holisticeducation.htm (accessed 10.04.06).

Ingram, R., 1991. Why does nursing need theory? Journal of

Advanced Nursing 16 (3), 350–353.

Jackson, C., 2004. Healing ourselves, healing others: first in the

series. Holistic Nursing Practice 18 (2), 67–81.

Johns, C., 2004. Becoming a Reflective Practitioner, second ed.

Blackwell Publishing Oxford.

Junor, E.J., Hole, D.J., Gillis, C.R., 1994. Management of

ovarian cancer: referral to a multidisciplinary team members. British Journal of Cancer 70 (2), 363–370.

Kenney, J.W., 2001. Philosophical and Theoretical perspectives

for Advanced Nursing Practice. Jones and Bartlett Publishers,

Boston.

Kolcaba, R., 1997. The primary holisms in nursing. Journal of

Advanced Nursing 25 (2), 290–296.

Leddy, S., Pepper, J., 1993. Conceptual Bases of Professional

Nursing, third ed. Lippincott Company, Philadelphia.

Leininger, M.M., 1988. Leininger’s theory of nursing: cultural

care diversity and universality. Nursing Science Quarterly 4,

152–160.

Levine, M.E., 1971. Holistic nursing. Nursing Clinics of North

America 6 (2), 253–264.

Martsolf, D.S., Mickley, J.R., 1998. The concept of spirituality in

nursing theories: different world-views and external of

focus. Journal of Advanced Nursing 27 (2), 294–303.

McBrien, B., 2006. A concept analysis of spiritually. British

Journal of Nursing 15 (1), 42–45.

McKenna, H., 1997. Nursing Theories and Models. Routledge,

London.

McSherry, W., 1998. Nurses’ perceptions of spirituality and

spiritual care. Nursing Standard 13, 36–40.

Meraviglia, M.G., 1999. Critical analysis of spirituality and its

empirical indicators: Prayer and meaning in life. Journal of

Holistic Nursing 17, 18–33.

Montgomery Dossey, B., Keegan, L., Guzzetta, C.E., Kolkmeier,

L.G. (Eds.), 2005. Holistic Nursing: A Handbook for Practice.

Aspen, Rockville, MD.

419

Narayanasamy, A., 1999. ASSET: a model for action spirituality

and spiritual care education and training in nursing. Nurse

Education Today 19, 274–285.

Nichols, K., 1992. Understanding support. Nursing Times 88 (13),

34–35.

Olive, P., 2003. The holistic nursing care of patients with minor

injuries attending the A + E department. Accident and

Emergency Nursing 11, 27–32.

Owen, M.J., Holmes, C.A., 1993. ‘‘Holism’’ in the discourse of

nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing 18, 1688–1695.

Paley, J., 1996. How not to clarify concepts in nursing. Journal

of Advanced Nursing 24 (3), 572–578.

Patterson, E., 1998. The philosophy and physics of holistic

health care: spiritual healing as a workable interpretation.

Journal of Advanced Nursing 27 (2), 287–293.

Rodgers, B.L., 1989. Concept analysis and the development of

nursing knowledge; the evolutionary cycle. Journal of

Advanced Nursing 14, 330–335.

Rogers, M.E., 1970. An Introduction to the Theoretical Basis of

Nursing. F.A. Davis, Philadelphia.

Smart, F., 2005. The whole truth? Nursing Management 11 (9),

17–19.

Smuts, J.C., 1926. Holism and Evolution. Macmillan, New York.

Villagomeza, L., 2005. Spiritual distress in adult cancer patients:

towards conceptual clarity. Holistic Nursing Practice 19 (6),

285–294.

Wadensten, B., Carlsson, M., 2003. Nursing theory views on how

to support the process of aging. Journal of Advanced Nursing

42 (2), 118–124.

Wilber, C.K., Harrison, R.S. 1978. Charles Wilber. University of

Notre Dame. <www.nd.edu/cwilber/pub/recent/edpehol.htm> (accessed 10.04.06).

Wong, T., Pang, S., 2000. Holism and caring: nursing in the

Chinese health care culture. Holistic Nursing Practice 15 (1),

12–21.

Walker, LO., Avant, K.C., 1995. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing. Appleton-Century-Crofts, Norwalk, CT.

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com