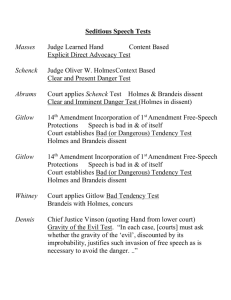

1 The American School of Historical Legal Thought

advertisement