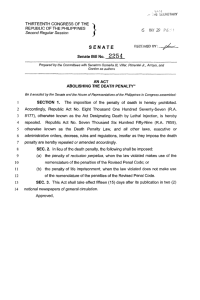

STATE OF CONNECTICUT COMMISSION ON THE DEATH

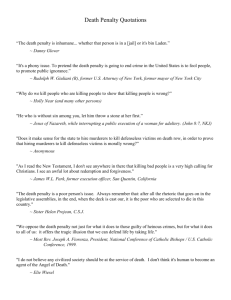

advertisement