Chall-Popp Phonics - Continental Press

advertisement

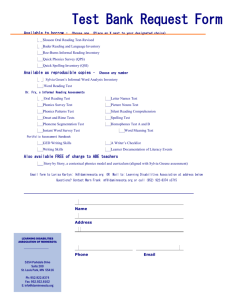

The Phonics Program from Continental Directly correlated to the five key skills identified by Reading First: Phonemic Awareness Phonics Fluency Vocabulary Comprehension Chall-Popp Phonics and Reading First One of the earliest researchers to recognize the instructional sequence for reading identified by No Child Left Behind, and required by Reading First, was Dr. Jeanne Chall of Harvard University Graduate School of Education. Dr. Chall and her colleague, Dr. Helen Popp, put into practice the results of well-founded research to create Chall-Popp Phonics, a program of instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, and fluency, as well as vocabulary and comprehension. The four books in the Chall-Popp Phonics program, the 48 Phonics Readers and 24 Find Out Readers that accompany them, align with Reading First and provide systematic, explicit instruction in phonemic awareness and phonics and address fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Instruction Chall-Popp Phonics Phonemic Awareness Levels A and B (K and 1) Phonics All Levels (K-3) Phonics Readers Fluency All Levels (K-3) Phonics Readers, Find Out Readers Vocabulary All Levels (K-3) Phonics Readers, Find Out Readers Comprehension All Levels Phonics Readers, Find Out Readers Continental 800.233.0759 Readers www.continentalpress.com 1 Chall-Popp Phonics Level A Phonemic Awareness Activities introduce each new sound. Phoneme Blending Phoneme Identity Phoneme Deletion Phoneme Blending Review the Sounds and Letters Children manipulate letters of the alphabet as part of phonemic awareness instruction. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 2 Chall-Popp Phonics Level A (Continued) Phonics Systematic, explicit instruction in phonics is the core of the program. Fluency Take-home stories written in natural language provide opportunities for reading controlled text. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 3 Chall-Popp Phonics Level A (Continued) Vocabulary Children acquire vocabulary both directly and indirectly as they learn phonics and read both Take-home stories and Early Phonics Readers. Chall-Popp Phonics Teacher’s Edition, Level A, page 118. Early Phonics Readers Teacher’s Guide, Short Vowels Set Two, page 7. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 4 Chall-Popp Phonics Level A (Continued) Comprehension Activities and scaffolding questions encourage children to be active readers. Chall-Popp Phonics Teacher’s Edition, Level A, page 62. Take-home story Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 5 Chall-Popp Phonics Level B Phonemic Awareness Phonemic awareness activities precede phonics lessons to insure that children have a firm foundation for learning sound-letter relationships. Chall-Popp Phonics Teacher’s Edition, Level B, page 61. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 6 Chall-Popp Phonics Level B (Continued) Phonics As part of systematic instruction in phonics, short vowel sounds are introduced using onset and rime. Chall-Popp Phonics Teacher’s Edition, Level B, page 41. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 7 Chall-Popp Phonics Level B (Continued) Fluency Take-home books in Chall-Popp Phonics, plus Phonics Readers, provide many opportunities for children to read aloud using the sound-letter relationships they have learned to achieve fluency. Early Phonics Reader, Book 2, cover, pages 2 and 8. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 8 Chall-Popp Phonics Level B (Continued) Vocabulary Children acquire vocabulary both directly and indirectly as they learn phonics and begin to read stories and use context clues. Phonics Readers and Find Out Readers introduce useful new vocabulary in fiction and nonfiction settings. Chall-Popp Phonics Teacher’s Edition, Level B, page 132. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 9 Chall-Popp Phonics Level B (Continued) Comprehension Children read decodable stories, including the Phonics Readers. The Teacher’s Guide provides suggestions to encourage children to monitor their own reading. Phonics Readers, Book 5, Ice for Sale, cover and page 5. Chall-Popp Phonics Teacher’s Edition, Level B, pages 157 and 158. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 10 Chall-Popp Phonics Level C Phonics Early units at this level provide instruction and reinforcement for those students whose skills are not firmly in place. Later units move into language structures and higher level phonics/spelling skills. Chall-Popp Phonics Student Book, Level C, pages 75 and 76. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 11 Chall-Popp Phonics Level C (Continued) Fluency At this stage, students can be encouraged to read aloud the poems that introduce each unit as well as the Take-home books, Phonics Readers, and Find Out Readers. Chall-Popp Phonics Teacher’s Edition, Level C, page 129. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 12 Chall-Popp Phonics Level C (Continued) Vocabulary The Phonics Readers and stories in Level C introduce relevant vocabulary for everyday reading. Prefixes and suffixes, synonyms, antonyms, and homonyms are introduced. Vocabulary for reading nonfiction is introduced as well in the Discover Nature Take-home books and the Find Out Readers. Find Out Reader, Book 10, Weather Chall-Popp Phonics Teacher’s Edition, Level C, page 161. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 13 Chall-Popp Phonics Level C (Continued) Comprehension The Discover Nature Take-home books and Reading a Story and Writing activities in Chall-Popp Phonics Level C, along with recommended library books for reading, help students establish their understanding of text. Chall-Popp Phonics Teacher’s Edition, Level C, page 156. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 14 Chall-Popp Phonics Level D Phonics Units 1, 2, and 3 of Level D provide a complete review of phonics principles for those students who are in need of instruction or review. Older students whose skills are in doubt will benefit from the review. Chall-Popp Phonics Student Book, Level D, page 10. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 15 Chall-Popp Phonics Level D (Continued) Vocabulary In addition to story vocabulary taught in earlier units, Unit 4 includes higher level phonics/spelling skills such as silent letters. The last two units focus on language skills that develop vocabulary such as prefixes and suffixes, synonyms and antonyms. Unit 6 introduces the dictionary. Chall-Popp Phonics Student Book, Level D, pages 137 and 138. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 16 Chall-Popp Phonics Level D (Continued) Fluency Throughout Level D there are nonfiction articles for students to read aloud in groups or silently. Tales from Around the World are included in each unit. These longer reading selections are recommended for group reading. Chall-Popp Phonics Teacher’s Edition, Level D, page 128. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 17 Chall-Popp Phonics Level D (Continued) Comprehension The Teacher’s Edition provides suggestions to help students gain meaning from their reading. Library books related to each selection are also suggested with each selection. Chall-Popp Phonics Teacher’s Edition, Level D, page 127. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 18 How Research Guided the Development of Chall-Popp Phonics The Chall-Popp Phonics program was created because more than 70 years of research has shown that children who learn phonics achieve better scores on tests of word identification, accuracy of oral reading, silent reading comprehension, and fluency than those who do not learn phonics. Perhaps the earliest and most dependable research was that of Jeanne Chall herself (Learning to Read: The Great Debate, Stages of Reading Development). Beginning to Read: Thinking and Learning About Print, by Marilyn Jager Adams, published in 1990, provided a thorough analysis of the research that reached the same conclusion. More recently, the report of the National Reading Panel showed that research continues to attest to the value of direct, explicit instruction in phonics. Other studies of importance include those by Grossen, Perfetti, Feitelson, Iverson and Tunmer, and Snow, Burns, and Griffin. The instructional design of Chall-Popp Phonics was guided by research on prerequisites to reading: phonemic awareness and visual discrimination, phonic generalizations and word patterns, syllabication, the study of affixes, and automaticity. Teachers are alerted to the prerequisite skills, outlined by Helen Popp, that may slow down the student’s progress in acquiring reading skills. Those explicitly addressed in Level A (kindergarten) include instructional vocabulary; concepts about letters, words, sentences, and stories; the concept that print represents sound in a left to right, top to bottom sequence; and motor skills (letter tracing). Research over many years by I.Y. Liberman and colleagues focused on the importance of phonological tasks and phonemic awareness. Similarly, Chall, Roswell, and Blumenthal, Durkin and others have found that phonemic awareness was a strong factor in the success of beginning reading instruction. Chall-Popp Phonics emphasizes these skills systematically through rhyming, segmentation, blending, hearing sounds that are represented by initial and final consonants and also vowels, consonant substitution, and eventually syllabication. The use of phonograms (onset and rime) as a vehicle for segmenting and blending is supported by the work of Wylie and Durrell, as well as Treiman. Empirical evidence in support of a best order for teaching the letter/sound correspondences and generalizations is not definitive, but research evidence does support the decision to teach first those single Continental 800.233.0759 by Helen M. Popp consonant letter correspondences that are discriminated more easily, both visually (Popp) and orally (Francis); those sounds that are more easily sounded in isolation (Francis); and those which in combination yield a large number of high frequency single-syllable words (see the studies of Venezky, Clymer, and Roswell and Chall). In Chall-Popp Phonics the most useful phonic elements and generalizations for identifying words are taught earliest; the harder or less reliable generalizations are taught later in the program. As an extension of decoding instruction, children are taught to look at chunks of words—first with syllabication and then with affixes. Sternberg and Powell and O’Rourke provide evidence that even older students are not aware that deconstructing words into their parts can help with deriving their meanings. In his summary, Stahl states that facility and ease in identifying polysyllabic words, and in inferring their meanings from a knowledge of prefixes, suffixes, and roots, helps students with comprehension. Chall-Popp Phonics teaches strategies for breaking words into their component parts using syllables and affixes. The prefixes and suffixes selected for inclusion in the program are based on the research of White, Sowell, and Yanagihara, who found that third graders who were given training on the nine most frequent prefixes and a strategy for deconstructing words into roots and affixes performed better than a control group on several measures of word meaning. Research also guided the creation of the pages in the Chall-Popp Phonics student books. Formats for pages were tested informally with students and teachers in selected Cambridge, Massachusetts, schools; teachers who have used the program also provided feedback and were helpful in making decisions for the latest edition. Research has also shown that a teacher is critical to the success that students achieve in learning to read. John B. Carroll concluded that teachers who understand the fundamentals of the relationship of print to speech will be better equipped to help all their students. The teacher’s editions of Chall-Popp Phonics have been designed and written to provide specific background phonics information on every page for teachers who may not have had the advantage of formal study in teaching phonics. www.continentalpress.com 19 About the Authors Jeanne S. Chall Jeanne S. Chall, former professor at Harvard University, was director of the graduate program in reading and language at the Graduate School of Education. She founded the Harvard Reading Laboratory and was its director for 25 years. Dr. Chall was the author of more than 200 books, articles, and tests, including Learning to Read: The Great Debate, Stages of Reading Development, The Reading Crisis: Why Poor Children Fall Behind, and the Dale-Chall readability formula. Dr. Chall served on the Board of Directors of the International Reading Association and the National Society for the Study of Education. She was a member of the National Academy of Education and the Reading Hall of Fame. Dr. Chall was honored for her research and scholarship by many associations, including the American Psychological Association, the American Educational Research Association, the International Dyslexia Association, and the International Reading Association. Helen M. Popp Helen M. Popp is a former Associate Professor of Education at Harvard University. She has worked with students and educators for many years on relating theory and research to reading instruction. Challenged by her earlier work as a librarian and primary school teacher, Dr. Popp focused her research and instruction on young children’s acquisition of reading as well as the development of their skill and interest in reading. Dr. Popp has written many articles and has been a member of the editorial board of the Harvard Educational Review. She has served as a consultant/advisor to many projects and organizations, including Project Literacy at Cornell University, WGBH-TV, Boston, the Children’s Television Workshop, the National Institute of Education, and the U.S. Office of Education. She has been active in the International Reading Association, the American Education Research Association, and the National Council of Teachers of English. Continental 800.233.0759 www.continentalpress.com 20 References Adams, Marilyn J. Beginning to Read: Thinking and Learning About Print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990. Perfetti, C.A. Reading Ability. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985. Carroll, John B. “Thoughts on Reading and Phonics,” (paper presented at the meeting of the National Conference on Research in English), Atlanta, GA, May 9, 1990. Perfetti, C.A. “Language Comprehension and Fast Decoding: Some Prerequisites for Skilled Reading Comprehension.” In J. T. Guthrie (Ed.) Cognition, Curriculum and Comprehension. Newark, DE: International Reading Association, 1977. Chall, Jeanne S. Learning to Read: The Great Debate. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1967 & 1983. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace, 1996. Popp, Helen. “Selecting Initial Reading Instruction for High-Risk Children,” in Bulletin of the Orton Society, XXVIII: 1978. Chall, Jeanne S., and Feldman, Shirley. “First Grade Reading: An Analysis of the Interactions of Professed Methods, Teacher Implementation and Child Background,” The Reading Teacher, 19 (1996): 569-575. Roswell, Florence G. and Chall, Jeanne S. Creating Successful Readers: A Practical Guide to Testing and Teaching at All Levels. Chicago: Riverside Publishing, 1994. Chall, Jeanne S. and Popp, Helen. Teaching and Assessing Phonics: Why, What, When, and How. Cambridge, MA: Educators Publishing Service, 1996. Snow, C.E., Burns, M.S., and Griffin, P. (Eds.) Preventing Reading Difficulties in Young Children. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1998. Chall, Jeanne S., Roswell, Florence and Blumenthal, S. “Auditory Blending Ability: A Factor in Success in Beginning Reading,” The Reading Teacher, 17 (1963): 113-118. Stahl, S. A. Vocabulary Development. Cambridge, MA: Brookline Books, 1999. Clymer, Theodore. “The Utility of Phonic Generalizations in the Primary Grades,” The Reading Teacher, 16 (1963): 252-258. Sternberg, R. J. “Most Words Are Learned From Context.” In M.C. McKeown & M.E. Curtis (Eds.) The Acquisition of Word Meanings (pp. 89-106). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1987. Durkin, Dolores. “Early Readers—Reflections after Six Years of Research,” The Reading Teacher, 18 (1964): 3-7. Feitelson, D. Facts and Fads in Beginning Reading. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation, 1988. Francis, W. Nelson. The Structure of American English. New York: Ronald Press, 1958. Grossen, Bonita. “Thirty Years of Research: What We Now Know About How Children Learn to Read.” National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Research Program, 1997. Iverson, Sandra and Tunmer, William E. “Phonological Processing Skills and the Reading Recovery Program,” Journal of Educational Psychology, 85 (1993): 112-126. Liberman I. Y. “Segmentation of the Spoken Word and Reading Acquisition,” Bulletin of the Orton Society, 23 (1973): 65-77. Continental 800.233.0759 Stanovich, K. “Romance and Reason,” The Reading Teacher, 17 (1963): 113-118. Treiman, R. “Onsets and Rimes as Units of Spoken Syllables: Evidence from Children,” Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 39: 161-181. Venezky, Richard L. “English Orthography: Its Graphical Structure and Its Relation to Sound,” Reading Research Quarterly, 2, (1967) 75-105. Venezky, R.L. The Structure of English Orthography. The Hague: Mouton & Co., 1970. Weir, Ruth and Venezky, R.L. “Rules to Aid in the Teaching of Reading.” (Final Report, Cooperative Research Project No. 2584) Stanford University, 1965. White, T.G., Sowell, J., and Yanagihara, A. “Teaching Elementary Students to Use Word-part Clues.” The Reading Teacher, 42, (1989): 302-309. Wylie, R., and Durrell, D. “Teaching Vowels Through Phonograms.” Elementary English, 47, 787-791. www.continentalpress.com 21 Reading First National Grant Initiative ©2006 Continental Press L02650 Revised 9/11