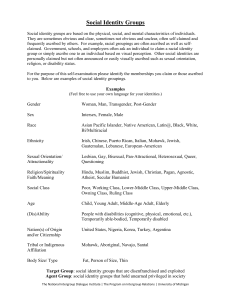

Studying Intergroup Relations Embedded in Organizations

advertisement