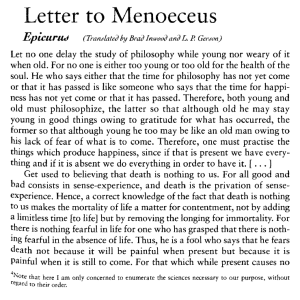

Plato's Republic and Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics

advertisement